Why East Asia has performed well in containing Covid-19

In the global effort to control the coronavirus situation, East Asia has been one of the best performing regions of the world. Here, we see expeditious action, effective measures, low fatality rates, and hardly any noise made in opposition to the anti-Covid measures. It is also the first region to show economic recovery.

This is not the first time that East Asia has stood out positively. People are familiar with the "East Asian miracle" that came after the Second World War: Japan, the four little dragons (Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea), followed by the four little tigers (Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam), not to mention the one colossus that grows the fastest, enjoys growth over the longest time, and is presently reshaping the very gestalt of the world - mainland China. Almost all the countries that have successfully escaped the middle income trap after the war are concentrated in this region.

The East Asian miracle has shifted the centre of global economy towards this part of the world, sparking widespread academic discussions about possible explanations of the miracle. Topics of discussion that garner more attention than others include the edge bestowed by the "developmental state" and cultural traditions, which ultimately can be chalked up to the unique social contract of this region.

Uniqueness of the East Asian social contract

The last time that the international community gave more focused attention to the East Asian social contract was during the 1990s controversy over "Asian values". It occurred against the backdrop of two concurrent phenomena - one was post-Cold War neoliberalism basking in its own success; the other was the flourishing of the East Asian miracle. The two were actually not speaking the same language. Led by the victorious West, the UN decided to hold the World Conference on Human Rights in June 1993. It was to promote the "universal values" that triumphed in the Cold War.

The Western mainstream sneers at the notion of "Asian values", dismissing it as nothing but a fig leaf and a convenient shield for dictators.

However, the East Asian countries, also triumphant in their own way, were feeling uneasy over this issue. In March of the same year, they held the Regional Meeting for Asia of the World Conference on Human Rights. They issued the Bangkok Declaration, setting forth the superiority of the Asian concept of human rights which stresses on collectivism. As pointed out, for example, by Singapore's founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, Asian values - such as respect for authority, giving weight to familial ethics, as well as the priority of collective interests over the individual's interests - not only contribute to social stability and economic development, but also help to avoid many of the problems of Western societies, such as broken families, social unrest, high crime rates and so on.

Notwithstanding, the Western mainstream sneers at the notion of "Asian values", dismissing it as nothing but a fig leaf and a convenient shield for dictators. While surprised by the success of the non-liberalist system, it does not make a good effort to try to understand, but instead turns its sense of superiority into the habit of lecturing and pointing figures. Even so, the fact is that the East Asian countries not only enjoy rapid economic development, but also commonly outdo the Western countries in terms of their competencies for social governance, situational response and dealing with disasters. Evident in the facts are the strengths of the social contract that has been developed within Eastern cultures.

The innate flaws of the liberalist discursive system

What clouds the Western mind is not just a sense of superiority. More significantly, there are some innate flaws in the liberalist discursive system, and from them stem certain blind spots and weaknesses in the social contract.

The inequality of initial conditions aside, capabilities can differ by a great deal between individuals, and so competing on a level playing field will necessarily result in inequality. Such inequality is further bolstered by the influence of money over the workings of democratic politics, as well as the advantages enjoyed by capital amid globalisation.

Historically speaking, the rise of liberalism was a revolt against monarchical power, the church and other traditional authorities, representing a new order propelled by industrial capital. The ideology is thus innately wired to value personal rights and liberties. Its presuppositions about the government are entirely negative. Accordingly, the government's propensity for doing evil has to be restricted through various means, such as the separation of powers, checks and balances, human rights, the rule of law and limited government. At the same time, liberalism offers no adequate theory with respect to the government's role in economic development, social management and situational responses. The East Asian developmental state goes beyond its imagination. Its limited universe of discourse leaves no room for the possibility that a strong government can also be a good government. Its focus on personal rights also causes it to overlook what the collective can achieve. In addition, it can produce no decent solution when dealing with social diversity, because this matter was not a salient issue at the time of its emergence.

The values of liberalism themselves are in conflict with one another. The most outstanding conflict is that between freedom and equality. Capitalism is society predicated on intense competition. The inequality of initial conditions aside, capabilities can differ by a great deal between individuals, and so competing on a level playing field will necessarily result in inequality. Such inequality is further bolstered by the influence of money over the workings of democratic politics, as well as the advantages enjoyed by capital amid globalisation. As a result, ideals like democracy, freedom, equality and human rights are often reduced to vacuous slogans and a facade for the hypocritical.

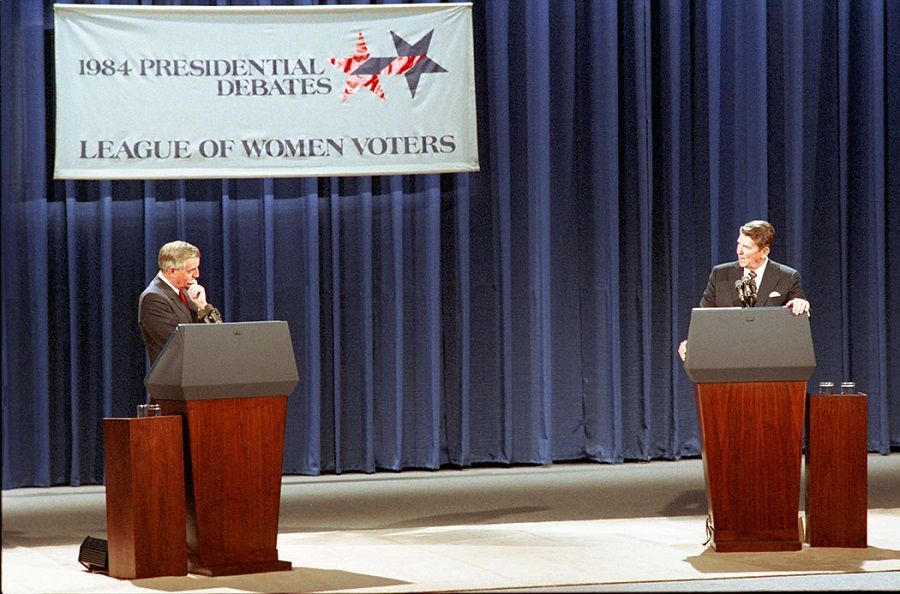

During his visit to the Soviet Union in the 1980s, US President Ronald Reagan once told the following story to promote America's belief in freedom and human rights. An old African American lady, according to him, was begging by the roadside outside of the White House. After being chased off by the police, she sued them, claiming that her right to do what she did in a public place had been violated, and she won the case in court. Liberalism can tolerate the starvation and homelessness of an individual, even her living in the streets for days on end until she freezes to death, but it will not stand for the deprivation of her metaphysical freedoms and rights. That is because, no matter how harsh they are, the results of market competition are rational and legal, and therefore acceptable. The deplorable state of the piteous bottom rung functions as a warning that they must work hard, or else they would suffer the same plight.

But what about the realities that liberalism now finds harder and harder to deal with? What about the polarisation of the rich and poor, society being torn apart and mired in unrest, the dissipation of the state's capacity to control the economic lifeblood and guarantee the provision of welfare to society? All these are the result of globalised competition. The US presidential election of 2020 has once again turned the spotlight on one particular fact: elections have become a mechanism for tearing society apart rather than for social consolidation. The president who lost refuses to concede, and yet he enjoys the support of a great number of people. Despite having lost the election, Donald Trump actually gained 10 million more votes than when he won four years ago.

In the massive protests against racial discrimination which took place not long ago, the occurrences of acts of violence like looting and shooting signify disillusionment with the system. As president, Trump did not make an effort to strike a balance amid the differences of opposing parties and maintain social solidarity in accordance with the American political tradition. Instead, he openly exploited the dividedness of American society, and pitted one side against the other. Democratic politics has become less and less constructive. The religious, cultural, racial and class conflicts in the West arising from various migrant movements are also putting the existing social contract in great distress.

In contrast, the East Asian social contract shows a greater advantage in chaotic times. From the liberalist perspective, this contract bestows the state with too much power, leading inevitably to abuse. But the East Asian contract actually posits a kind of government-people relation that is very different from what the West has. Here, the people find their freedoms in some aspects being restricted to various degrees, but they also gain more in other aspects, which are often the more important facets to them. For example, in vital matters like social security, economic growth, the continuous elevation of the quality of life, as well as infrastructural improvements, the people can expect active responses from their government. In contrast, the price for capitalist freedom is that everyone has to struggle on their own to survive - and when they fail, they often face disdain from society and the indifference of their government.

The liberalist social contract is focused on limiting power, on ensuring that the government is unable to do evil. However, in the historical and cultural traditions of East Asia, the people care more about empowering the government to get things done for the masses.

The East Asian social contract is a cultural contract

The East Asian social contract is a kind of "cultural contract". While it has not developed into a system as complete and explicit as its liberalist counterpart, it has a very wide coverage. The contract acknowledges, among other things, to what extent the government can move into personal space. It also entails a certain expectation on the people's part. They expect their government to shoulder a broader range of responsibilities, certainly broader than what is delimited by liberalism. The control that such "unlimited government" has over society is, of course, much stronger than that of the limited or small government as conceived by the West. However, unlike what the liberalists assume, such control is not merely good for abuses of power and corruption. It can accomplish much that is beyond the capabilities of the liberal limited state, especially in responding to upheavals.

The liberalist social contract is focused on limiting power, on ensuring that the government is unable to do evil. However, in the historical and cultural traditions of East Asia, the people care more about empowering the government to get things done for the masses. Herein lies the most important difference between two types of social contract. In the eyes of the liberalists, such latitude can only lead to corruption, autocratic behaviour, violation of human rights, as well as suppression of freedom and individuality. In the East Asian countries, however, the government is expected by its people to wield its authority for their good and for the glory of their nation.

Such expectations tie in with what is known in East Asia's political vocabulary - especially within the Confucian cultural sphere - as "winning the hearts of the people", with or without an election. Differences in the matter of corruption, for example, is quite revealing. In some Third World countries, corrupt rulers tend to pocket their ill-gotten money and not do their job, with no prick of conscience felt. In East Asia, however, even corrupt officials have to get things done. That's because only by obtaining results can those in power win the hearts of the people and ensure the continuance of the "Mandate of Heaven", so to speak.

The edge of liberalism lies in its having direct value for every person, which makes it widely appealing and very easy to spread. Such value on the level of the individual is something no government can overlook. It has to be taken seriously.

Getting things done requires working hard, taking risks and coordinating and working with different parties. To the liberalists, to whom the holders of power are axiomatically predatory, the rational pattern of behaviour for a government that lacks checks and balances would be to grab more money and do less work. It would not make sense to grab more money and do more work too. At least it should not happen in a widespread and sustained manner. In East Asia, holders of power, including some of the Chinese Communist Party's officials, often show commendable performance in their work even when they are notoriously corrupt. That is probably one important reason for the success of post-war East Asia.

The social contracts of the East and the West each have their own lacunae. They are both imperfect. The two are not mutually exclusive, but should complement each other instead. The edge of liberalism lies in its having direct value for every person, which makes it widely appealing and very easy to spread. Such value on the level of the individual is something no government can overlook. It has to be taken seriously.

Asian countries have by now accepted the ideas and systems of liberalism to different extents, just as they are variously infected with the pathologies of the West. The East Asian social contract needs to be articulated more clearly. It needs to be systematiThe liberalist discursive system leaves little room for one to contemplate the possibility that a strong government can also be a good government, much less the positives of the East Asian developmental state or Asian values. In fact, under the East Asian social contract, people are willing to empower the government for greater outcomes for all, and the government works to win the approval of the people as a means to preserve their legitimacy. Now, when malfunctions in the liberalist social contract are laid bare by Covid-19 and other crises, it may be worth taking a closer look at the merits of the East Asian social contract. sed and explicitly itemised, so that we may lucidly understand its weaknesses, the relationship between its strengths and failings, as well as what there might be in the Western social contract that it can learn from on one hand and must reject on the other.

The flaws of the liberalist social contract are being gradually exposed by the changing times. The failing system needs to assimilate some of the virtues of the Eastern contract. Some of the developments over the better part of this year are illustrative enough. For example, when China adopted a series of stringent measures to control the spread of Covid-19, the West went into uproar initially, angrily criticising the "totalitarian system" for violating human rights and suppressing freedom; and yet it was not long before the accusers had to adopt the same or similar measures for themselves too. In any case, in order to truly acquire the governance competency of East Asia, the Western social contract has to change. Some adjustments to its contents are surely necessary.

Related: Liberalism and globalisation serves the elites; the world needs a return to the nation state | If the world needs a new ideology, can the Chinese model be accepted? | Wang Gungwu: Even if the West has lost its way, China may not be heir apparent | Covid-19: East Asia must play a greater role