Woman traveller of the Qing dynasty Qian Shan Shili: Education is the bedrock of a nation

Recently, a good friend at a publishing house was busy preparing a book series for publication. To be called Classic Travelogues for the Young (经典少年游), the compendium is tailored to a teenage audience and would feature over 100 Chinese classics under eight headings such as poetry, philosophy, biography and technology. Lively images and diagrams would be included to pique the interest and stimulate the intellect of the young reader. My friend asked if I would be a consultant on the "Adventure and Geography" section and help with the selection of works to be included. The series was clearly aimed at growing young minds by improving their cultural knowledge and sparking thought on the modern significance of cultural traditions. As it was an extremely important cultural work, I immediately agreed to help. My friend then sent over the proposal and preliminary book list.

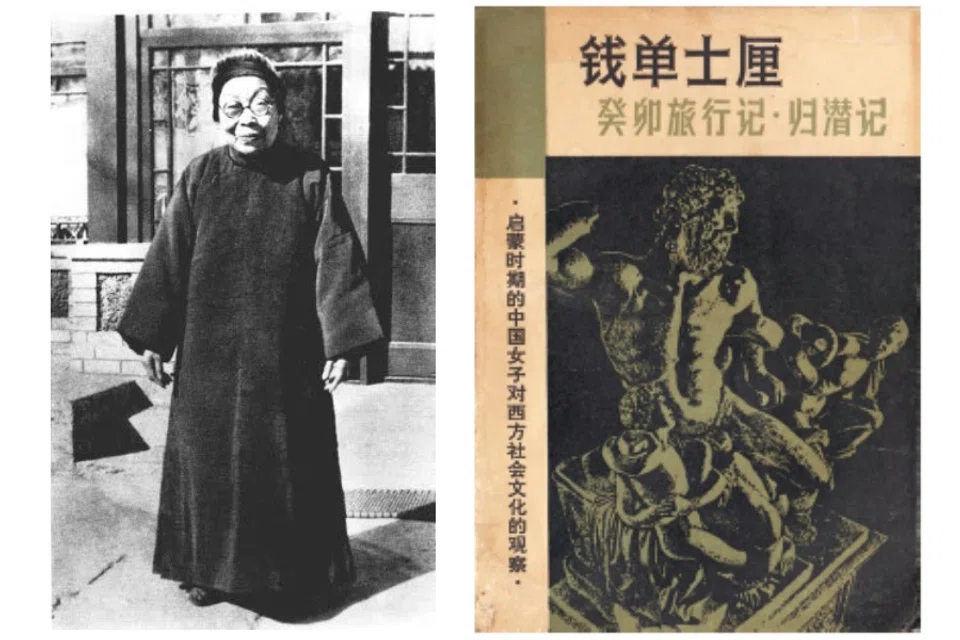

I looked at the book list and thought that it was mostly OK. It included adventure books like Great Tang Records on the Western Regions (《大唐西域记》) and Xu Xiake's Travels (《徐霞客游记》), as well as geography books like Commentary on the Water Classic (《水经注》) and Dongjing Meng Hua Lu (《东京梦华录》or "Dreams of Splendour of the Eastern Capital"). However, a book written in the late Qing caught my attention: Wei Yuan's Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms (《海国图志》). While the book is a seminal work of the late Qing period about other countries and was a window to the world for the then isolated Chinese, Wei compiled the information on foreign lands in a crude manner. He merely copied Lin Zexu's* compilation of material from abroad with no real understanding of these materials, and packaged them as he needed to before publishing the book. Put bluntly, it is akin to the raw data compiled by the archival section of news agencies - i.e. unprocessed data that are really not opinions or interpretations of the data at all. Thus, I suggested swapping the book with two travelogues of Qian Shan Shili, Gui Mao Lvxing Ji (《癸卯旅行记》or "Travel Notes From 1903") and Guiqian Ji (《归濳记》 or "From My Study, Guiqian").

Travel as a form of education

Who was Qian Shan Shili (1856-1943)? I'm afraid most people have never heard of her. Actually, she was a great woman of the late Qing and early Republic period. "If that's the case, why isn't she more well-known?" I hear some people asking. Then we only have ourselves to blame. As the saying goes, it takes Bo Le (a horse scout from the Spring and Autumn period) to spot a fine horse (伯乐相马, meaning it takes a keen eye to spot hidden talent). If we can't see beyond the end of our noses, even if someone gives us a piece of precious Hetian jade (和田玉), we would think that it's a piece of useless rock and toss it into the bin.

Her two travelogues contain detailed accounts of her personal travels in Japan, Korea, Russia, and Europe, and the comparisons she made from what she saw with Chinese cultural traditions. Her views remain thought-provoking even until today.

You might have heard of Qian Shan Shili's family members. Her husband Qian Xun was a diplomat during the late Qing period, the elder brother of Qian Xuantong (a renowned Chinese linguist), and also a secret member of the Guangfuhui (光复会, Restoration Society, an anti-Qing organisation). Her son Qian Daosun was a renowned translator, while her nephew Qian Sanqiang was a famous scientist. However, Qian Shan's greatness does not derive from her family's achievements, but from her own experiences and wisdom, as well as her incisive insights into world trends and China's future. Her two travelogues contain detailed accounts of her personal travels in Japan, Korea, Russia, and Europe, and of the comparisons she made between what she saw and what she knew of Chinese cultural traditions. Her views remain thought-provoking even until today.

Much to learn from Japan's education system

In the 29th year of Guangxu Emperor's reign (1903, Gui Mao Year of the Rabbit), Qian Shan travelled from Tokyo to Osaka, visiting the Fifth National Industrial Exhibition of 1903. After viewing the exhibits in the education pavilion, she strongly felt that Japan had its education system to thank for its progress. She said, "The reason why Japan has a place in the world today, the reason why it is able to come back from the brink of destruction and take its place among the strong powers, is because of its education system." She thus concluded that education was the bedrock of a nation.

Qian Shan was emphasising the importance of national (public) education, specifically during the periods of primary and secondary school.

She further said, "A nation is built by its people, and people are built by education. Teaching begets education; bringing up a generation involves education in all aspects, including moral, intellectual and physical education. The crucial window in education is when students are in primary school i.e. when they are about ten years old, to the time that they are in secondary school or about five years after their primary school education. At these stages, Japanese education is not too profound, nor too taxing on the brain, but yet focused on the necessary scientific knowledge across a wide range of areas. The Japanese have done well in this!" Qian Shan was emphasising the importance of national (public) education, specifically during the periods of primary and secondary school.

In contrast, Qian Shan harshly criticised the new education model that was introduced to China in the late Qing. She pointed out that in the past, people only studied classical traditions. But after reform and opening up, people started to pick up foreign languages. She asked if such teachings could truly nurture good citizens of new China? If the Chinese people only learnt foreign languages but had no knowledge of their native language, what kind of citizens was the country moulding? She believed that each individual should first and foremost be nurtured into self-respecting citizens of the country. She also stressed the importance of providing education for females.

And even when men are educated, the best among them become government officials, while the rest simply use it to make a living. What a pity! - Qian Shan Shili

Females are the first educators in a child's life

She reasoned: "The primary purpose of education is to nurture good citizens of a country, and not to shore up a reserve of talents for the government. Thus, both men and women should have access to education. In fact, a child's first educator is often his or her mother. On that basis, it is even more crucial to impart education to females of the country. While education has been given more emphasis in recent years, the focus remains on nurturing exceptional talents and not on the individual citizens that made up the general population. Hence, few people talk about education for women. And even when men are educated, the best among them become government officials, while the rest simply use it to make a living. What a pity! Without citizens, how can there be talents? Without citizens, there can be no society! China's prospects are like a rooster yet to sing. Seeing Japan's education pavilion, I can only lament the sad state of China's education."

Qian Shan's criticisms of the new education model in the late Qing period can be summarised in two main points. One, that the goal of public education should not be to train a group of elites who would serve the government but to nurture new citizens who could think independently and build a new society. Two, to pay special attention to female education and understand that a child's growth is closely related to the teachings of his or her mother. Thus, education for females should not be neglected when speaking about the fundamentals of education. These century-old opinions remain relevant today.

I hope that the younger generation will realise that Qian Shan was not only "the first woman to write about her overseas travels" but also an amazing woman with great wisdom as well.

* Lin Zexu (1785-1850) was a prominent Qing dynasty scholar and official who was involved in implementing policies leading to the First Opium War, which ended in 1842 with the signing of the Treaty of Nanjing. Lin collected and translated clippings from books and newspapers from the West as he wanted to know the Western world better. He later passed this material to Wei Yuan, who published the Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms in 1843.