AUKUS and Quad do not solve India's regional security problems

A rapid power grab by the Afghan Taliban, Pakistan's neighbouring protégé, followed the complete withdrawal by US and allied forces from Afghanistan in August 2021. Even as chaotic scenes and a humanitarian crisis marked the US departure, China began campaigning for a Taliban-led order in Kabul.

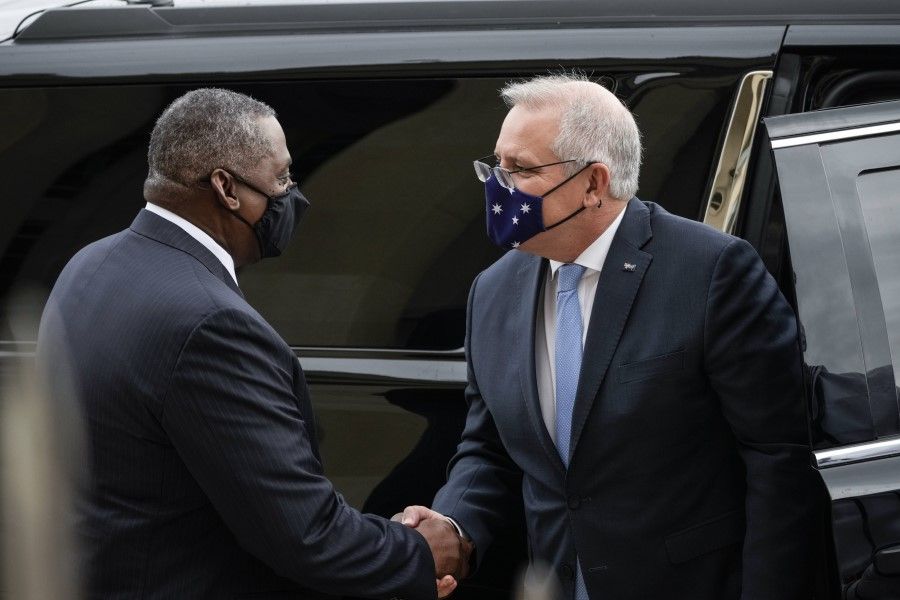

In the following month, on 15 September, Washington launched a new strategic pact, AUKUS, that links Australia with the UK and the US. On the eve of this pact, Canberra-Beijing ties had been in deep freeze. US President Joe Biden, therefore, appeared to be challenging China which might gain from his Afghan exit. However, India is caught in the web of this US-China rivalry.

A China-led 'alternative Quad' ─ sans India?

India, like Australia and Japan, is a member of the US-led Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) group which is denounced by Beijing as a "closed, exclusive clique" that targets China.

On 16 September, the day after the launch of AUKUS, the foreign ministers of China, Russia and Pakistan as well as a representative of Iran met in Dushanbe (Tajikistan) to discuss the post-American Afghan situation. India, which has decades-long unsettled relations with both China and Pakistan, was excluded from this meeting at the margins of a multilateral summit.

India's exclusion from this apparent "alternative Quad" (this author's terminology) has a recent context as well. The United Nations Security Council, under the rotating presidency of India in August, adopted Resolution 2593, mandating dos and don'ts for the Taliban.

The resolution identified the promotion of international terrorism from Afghanistan as a red line not to be crossed by the Taliban. Norms such as the protection of rights of women and minorities were also recommended for the Taliban-led "interim government" in Kabul.

Before the US departure from Afghanistan, Delhi was not exposed to Sino-Pakistani pressure in that country. But the going is getting tough for India now.

Delhi's frustration

China and Russia, proactive in wooing and guiding the Taliban to promote their interests, abstained from voting on Resolution 2593. Beijing hopes that the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), in the proximity of Afghanistan, would be protected and extended to the Afghan areas under the Taliban's rule.

China has the power and resources to incentivise the Taliban. There is a retrospective reason, too. If the now-bygone American presence had stabilised Afghanistan, India as a US-friend might have even had a chance to threaten CPEC from the Afghan soil.

For Russia, increasingly alienated by Washington, the company of China, an erstwhile rival, is preferable rather than India, a traditional friend seen now as America's quasi-ally. For the same reason, Russia is moving closer to Pakistan, China's "all-weather" partner.

India, on its part, seeks to remain relevant to Afghanistan as its development partner. Before the US departure from Afghanistan, Delhi was not exposed to Sino-Pakistani pressure in that country. But the going is getting tough for India now.

With an almost-proprietorial interest in the Taliban-led Afghanistan, Pakistanis would like to use this country as a rear strategic terrain against India. This factor, too, may explain the exclusion of an anti-terror campaigner like India from the apparent Afghan-centred "alternative Quad".

Iran was also conspicuously absent from the talks held by representatives of China, Russia and Pakistan with the Taliban's "interim government" in Kabul on 21 and 22 September. Dissonance between the Islamic ideologies of Iran and the Afghan-Taliban-Pakistan front might, if not managed, become a fault-line in the "alternative Quad".

Fractured US-led Quad

The omission of an Indo-Pacific security agenda is a notable outcome of the first in-person summit of the US-led Quad in Washington on 24 September. Under Biden's stewardship, infrastructure development is to complement the Quad's existing regional agenda of Covid-19 vaccine production, future technologies and climate safeguards - all non-military initiatives.

From the time the Quad was launched in 2007 for informal security dialogue, there was no realistic expectation of creating a four-pronged military force to confront China. The forum's overwhelming collective emphasis on the maritime domain has also left India lonely in facing China along their disputed land frontier.

Even in the maritime domain, Delhi expressed "concern" over the transit of a US warship through the Indian exclusive economic zone in April 2021. There was mismatch between India's interpretation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and America's need for India as a maritime friend.

Washington seems to be bolstering an emerging anti-China challenger - Australia - instead of Beijing's old rivals India and Japan.

The Quad's Washington summit in September has also not endorsed the regular Malabar naval exercise among the four countries as a China-targeted war game. The pre-summit launch of AUKUS - in effect a security pact among Australia, the UK and the US - had in fact taken the wind out of the Quad's original sails.

Washington seems to be bolstering an emerging anti-China challenger - Australia - instead of Beijing's old rivals India and Japan. This may reflect Biden's new Indo-Pacific strategy. But the Quad's strategic focus on China may get divided between the US and Australia, on one side, and Japan as well as India on the other.

Decoded, Beijing has hinted that the AUKUS-threatened countries could take counter-measures which might trigger an arms race.

AUKUS's shadow over India

Looking beyond the latest trend in the Quad, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi has portrayed AUKUS as the harbinger of three potential dangers of Cold War resurgence, an arms race and nuclear proliferation in Asia and beyond.

The centrepiece of AUKUS, as initially disclosed, is the joint US-UK pledge to bolster Australia by enabling it to deploy nuclear-propelled submarines in due course. Through AUKUS, therefore, the US may be investing capital in the military domain to checkmate China and its close partners like Russia and Pakistan.

But Delhi will be looking for a concealed hint of concern to India itself in the Chinese denunciation of AUKUS. The catchphrases in this regard are arms race and nuclear proliferation.

Decoded, Beijing has hinted that the AUKUS-threatened countries could take counter-measures which might trigger an arms race. These countries could produce and deploy submarines which are propelled by nuclear reactors and/or used to unleash nuclear weapons.

India is not alone in being sure of China's contemporary role in helping Pakistan develop and deploy nuclear weapons and their delivery systems. The story is part of the global strategic narrative. Delhi might, therefore, look at Beijing's potential role in promoting Pakistan's nuclear submarine technologies. This is an Indian dilemma that the authors of AUKUS may not have anticipated.

This essay first appeared in RSIS Commentary, a publication of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore as "India's Afghan and AUKUS Dilemmas" by P. S. Suryanarayana.

Related: With AUKUS, Southeast Asia may become a more intense battleground | AUKUS: Aggravating tensions and dividing the world | Quad now centrepiece in India's China strategy | China has a long-term strategy in Southeast Asia. But what about India? | Afghanistan in the calculations of India, Pakistan and China: Is there common ground among rivals and allies?