The balcony: A metaphor for eroticism in Chinese literature

A balcony can simply be a perch from which to admire the sea, or for Shakespeare fans, it is associated with a key scene from Romeo and Juliet. For ancient Chinese literati however, it conjures up scenes of forbidden trysts and has been woven into poems by illustrious poets, from Song Yu to Li Bai and many others.

Admiring the sea from a balcony is a relaxing and enjoyable endeavour. With the vast ocean spreading out from the shore and graceful mountains disappearing into the distance, I feel a peace and quiet rarely found in Hong Kong.

I take a seat in an alfresco area. A novel is in my hand, like a prop for a scene. Perhaps I am meditating, but I am more likely just letting my mind saunter off.

Clouds float past. I stare at them in a daze, flipping through the novel. It is not about the story... Listen, the rustling of the pages is like the flapping and fluttering of wings of little egrets from afar.

"A flock of egrets fly over the vast paddy fields, and the songs of orioles ring out from the dense summer forests" - Tang dynasty poet Wang Wei thus described Wangchuan Villa in his poem (《积雨辋川庄作》). Why am I having similar sentiments as Wang in the middle of Hong Kong at the tail end of winter, and far away from the city centre?

A fuzzy laziness descends upon me as the sun's rays emanate across my back and over my body. I feel tingles in my toes. It is as if the French pointillism painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat has come to life and elegant ladies with dainty parasols are greeting me as they pass.

Building balconies in the air

When I was a young boy living in Taiwan, we called Western-style buildings "bungalows" (洋房 yangfang, lit. Caucasian house), and the balconies jutting out from the upper floors of these buildings 阳台 (yangtai, lit. sun platform), or 洋台 (yangtai, lit. Caucasian platform). It seemed that the terms were used interchangeably.

阳台 calls up the image of a place filled with sunshine, while 洋台 highlights the architectural origin of a Western-style building. But when I looked up an etymology dictionary (《词源正续编》, 1960) published by Taiwan's The Commercial Press in Taipei, I could only find 阳台 and not 洋台. Furthermore, the word refers to "the name of an ancient mountain or place", and the citation came from late Warring States period poet Song Yu's Gaotang Fu (《高唐赋》). It seems that the word 洋台 does not have a right to exist in official dictionaries.

Interestingly, the word 洋台 was born in the early days when Western culture was just making its way to the Eastern world. This was when cities exposed to foreign styles began to build Western-style buildings à la the famous balcony scene where Juliet poured out her heart's desire to Romeo in William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet.

For example, 洋台 was used to describe balconies of Western-style bungalows in the late Qing dynasty prostitution-themed literary work The Nine-tailed Turtle (《九尾龟》), which Chinese scholar Hu Shih described as "the ultimate guide to prostitution". In new literary works written in the 1930s of the 20th century, 洋台 was also frequently used and can be found in the books written by Lu Xun, Mao Dun, and Lin Yutang.

阳台 has become the standard form of the word in modern dictionaries that have gone through a century of character standardisation processes. 洋台 on the other hand is becoming obsolete and can hardly be found in any dictionary currently published.

The 1999 version of Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House's Cihai (《辞海》, a comprehensive dictionary and encyclopedia of Standard Chinese) provides two definitions of 阳台: 1. "The name of a legendary platform", referencing Song Yu's Gaotang Fu Xu (《高唐赋序》) with the elaboration that the word is "later used to refer to a place where man and woman engage in sexual activities"; and 2. "The platform outside the room of a new-style building". The word 洋台 is not included as an entry under the character 洋.

The 1993 version of Hanyu Da Cidian (《汉语大词典》) has three definitions of 阳台: 1. "The place where man and woman engage in sexual activities, as described in Song's Gaotang Fu Xu; 2. "The Taoist Wangwu Mountain area (清虚洞天)"; and 3. "The small platform outside the rooms of an upper floor". The word 洋台 is recorded under the character 洋 with a short and simple definition: "See 阳台".

In The Chinese-English Dictionary (Third Edition) edited by Gu Guanghua and published by the Shanghai Translation Publishing House in 2010 (《汉英大词典》), 阳台 is translated as "balcony, terrace, veranda". The word 洋台 is not included. In The English-Chinese Dictionary (Second Edition) edited by Lu Gusun and published by the Shanghai Translation Publishing House in 2007 (《英汉大辞典》), all three English words listed above are translated as 阳台, and not 洋台.

Observably, in modern Standard Chinese, 阳台 has replaced the form 洋台, which emerged in the late Qing dynasty and Republican era, and encompasses both the sexually-charged ancient usage of the word and the modern reference to the protruding space in Western architecture.

Sexual innuendo of 'the balcony'

Modern young people may find it hard to imagine the sexual connotations of the word balcony. The images they conjure up are at best that of the character Juliet in Shakespeare's play, and the way she spoke of her heart's longings when she called out to her beloved Romeo on the balcony set up on a stage. But mention the word 阳台 to ancient Chinese literati and their imaginations would run wild. Their minds would be filled with love and lust of yangtai yunyu (阳台云雨, cloud and rain on the balcony which also means "making love on the balcony" in Chinese). They would be reminded of the mythical meeting between King Xiang of Chu and the goddess of Wushan.

The second poem of Li Bai's Qing Ping Diao Ci (《清平调词》) goes: "So beautiful a fragrant, dewy red peony flower that even the yunyu between King Xiang of Chu and the goddess of Wushan cannot match. Which of the beauties in the Han palace can compare to her? Even Zhao Feiyan has to rely on makeup!" Here, Li makes reference to the erotic encounter or yunyu at Wushan. At that time, Li had received an imperial order and was writing about Consort Yang Guifei's seductive demeanour from the perspective of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, but he was too explicit with his words. No wonder some people thought that Li was taking advantage of Yang through his words. Yet, poets can also imagine very different things when it comes to Wushan and Wu Gorge.

For example, at the beginning of Du Fu's Qiu Xing Bashou (《秋兴八首》), it says, "The maple trees are slowly withering in the deep autumn, and Wushan and Wu Gorge are shrouded in a gloomy mist. The waves are roaring in the Wu Gorge, and dark clouds are looming above. The sky and the earth are enveloped in sombreness." For Du Fu, Wushan and Wu Gorge exude great magnificence and grandeur. But, for the most part, Wushan reminds one of the dreamy and erotic happenings at the mountain more in the vein of what is described in Li Shangyin's poem Guo Chugong (《过楚宫》): "The Wu Gorge is near the ancient Chu palace and its yunyu are still remembered today. Humanity is greedy for the joys of this earth, while King Xiang alone is lost in his dreams and memories."

In Chinese literary tradition, the balcony became associated with yunyu and all things sexual and erotic because of Song's Gaotang Fu and Shennv Fu (《神女赋》). The former ode goes like this: King Xiang and Song Yu were touring the Yunmeng lodge when they saw a strange cloud hovering over Gaotang pavilion in the distance. King Xiang asked Song what the cloud was all about, to which Song replied with the story of a previous king's meeting with the goddess of Wushan in a dream. After they made love, the goddess told the king, "I am at the southern side of Wushan amid dangerous mountains. I am a cloud in the morning and rainfall at night. Every morning and night, I live at the yangtai (阳台)." The latter ode goes like this: after King Xiang heard the story, he dreamt of the goddess at night but did not have a happy ending like the king in the former story. Thereafter, King Xiang woke up with endless sorrow and melancholy.

Scholars such as Tang dynasty's Li Shan and Northern Song era's Chen Shidao said that both of Song's rhapsodies were aimed at persuading King Xiang against indulging in sexual pleasures. But modern writer Qian Zhongshu's Limited Views (《管锥编》) offered a different interpretation. He believed that Gaotang Fu belonged to travel literature of the same kind as Sun Chuo's Tour of Tiantai Mountain (《游天台山赋》) and Li Bai's Tour of Tianlao Mountain (《梦游天姥吟留别》), and depicted an imaginative journey of Wushan and Wu Gorge. He did not think that it was necessarily an allegory of lust between man and woman. However, based on the way the story was cited in poems across history, it is clear that in the minds of ancient Chinese literati, 阳台云雨 (cloud and rain on the balcony) had obvious sexual connotations.

Literary works littered with references

This is reflected in Tang dynasty poet Liu Yuxi's Wushan Goddess Temple (《巫山神女庙》) which clearly describes the goddess of Wushan presenting herself to King Xiang on the night the pair made love. It says, "While she departed at the end of yunyu, she left behind an exotic fragrance".

Northern Song dynasty poet Ouyang Xiu also references the balcony in the description of a couple's longing for each other after separation in Amorous Red Apricot Tree (《梁州令·红杏墙头树》), with the phrases "a dream on the balcony is like experiencing yunyu" and now that spring has arrived and the flowers are blooming, "Oh where is my beloved?"

Even Southern Song dynasty Confucian scholar Zhu Xi's mind wandered as he made associations to the goddess of Wushan when he wrote about Yunv Peak (玉女峰) in Poems of Jiuqu River (《九曲棹歌》). He said: "Oh the beautiful and elegant Yunv Peak! Standing by the waters with flowers in your hair, for whom are you dressed for?" Thankfully, he quickly clarified that he was one who practiced asceticism and would not dream about the balcony or the things that happened there. We can never be sure if Zhu would have been like Liuxia Hui of the Spring and Autumn period, who managed to restrain himself in the presence of a beauty who threw herself into his arms. But Zhu was in charge of the Taoist Chongyou Temple at the Wuyi Mountains and was tasked to make sacrifices to God Wuyi. It was only right that he abstained from yunyu on the balcony.

Southern Song dynasty's military commander and poet Xin Qiji had also written a poem making reference to the goddess of Wushan. While his poem There Was Once A Beauty (《水龙吟·昔时曾有佳人》) mainly described a carefree life in the mountains, there were also occasions where attractive women came into the picture, making him confused and dazed. He said: "Look at the passing clouds and rains, morning and night, on the balcony, at the side of King Xiang." However, while Xin was indeed attracted to these ladies, he was able to remain a gentleman and not succumb to his lust. The noble and big-hearted ways of Xin could be likened to the ancients "reading a sword in drunkenness and in soft light" - indeed he was attracted and his imagination ran wild, but he also frankly admitted his feelings, while stopping himself from going beyond the morals of his times. Unlike Zhu, he did not deny all associations by quickly erecting walls of morality.

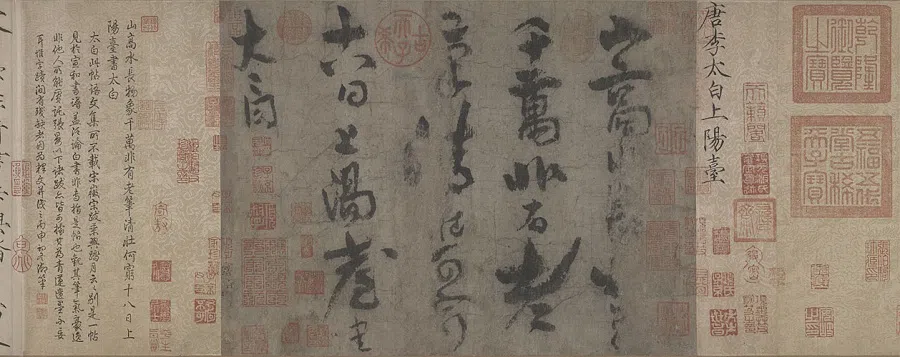

People familiar with the history of calligraphy would know that Li Bai's Ascent to Yangtai Temple (《上阳台帖》) - a piece of calligraphy that art collector and connoisseur Zhang Boju had given to Mao Zedong - is kept in Beijing's The Palace Museum. The piece consists of 25 words written in the semi-cursive script and is the only surviving work of Li. Yes, the same person who wrote Qing Ping Diao Ci had produced this artful piece of calligraphy about ascending a "balcony" (阳台) with powerful brush strokes. But here, the word 阳台 refers to the Taoist Wangwu Mountain area - not King Xiang's and the goddess of Wushan's meeting on the balcony.

This 阳台 on Wangwu Mountain can be seen as a place where one ascends in the spiritual realm, looking into the distance at the changing scenes of day and night, and experiencing harmony between man and nature. Taoist priest and a good friend of Li, Sima Chengzhen, built the Yangtai Temple on Wangwu Mountain during the Kaiyuan era of Emperor Xuanzong's reign. In the third year of the Tianbao era (744), Li visited the Yangtai Temple with Du Fu and Gao Shi, and wanted to pay his old friend Sima a visit. Unfortunately, Sima had already passed away and Li then penned the Ascent to Yangtai Temple. He wrote: "The mountains stand tall and the waters run far, the cosmic world exhibits its endless existence. If none has the ability to portray such wonders, how sad can we be?" Hence, the title of Li's work of calligraphy, "Ascent to Yangtai Temple", implies a desire to seek immortality and becoming one with the cosmic world, which is totally unrelated to the yunyu story on the balcony that Song Yu had left behind.

I sit on my balcony looking into the distance, letting my mind to wander. I can't help but marvel and sigh at the profundity of classical Chinese literature. There are so many nuances and ambiguities that the single act of sitting on the balcony can remind me of a whole host of classical and idiomatic stories.

While I am not imagining things, my thinking is probably very different from modern literary youths. Perhaps this is also what a generation gap means - when oldies like us daydream, we tend to bring up ancient times and return to age-old traditions.

This article was first published in Chinese on Wenhui as "每个人的心中都有一个阳台".

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)