Are the Chinese truly collecting art?

With China's increasing affluence, the nouveau riche are investing in art and cultural artefacts. Wu Zetian's pleated skirt, exquisite paper from the Southern Tang dynasty, a painting by early 20th century painter Qi Baishi - authentic or not, all are fair game and acquired at the best price. What a shame, says cultural historian Cheng Pei-kai. If only the collector's hand is not sullied by such commerce.

In recent years, China has become prosperous to the point that people are drowning in cash. To avoid being submerged, they splurge and throw their cash around, buying high-end luxury products, luxury sports cars, and villas abroad. The situation in China is so strange - a while ago, China wasn't so rich. Oil was rationed to 100g-150g per month, and people had to think twice about eating a bowl of shredded chicken noodles. In the end, they often settled for just a small bowl of plain noodle soup. How is it that in the blink of an eye, people have heaps of money that even gunny sacks or trucks can't contain? It's just like rubbish in the landfills - overwhelmingly tall and blocking the entrance, making it difficult for people to enter or leave.

With so much money at their disposal, people are at a loss as to what to do with it. They first satisfy their indulgences such as gluttony, alcoholism, lust, and gambling. But this soon proves too much for their bodies to handle. So they splurge on cultural artefacts and pick up an oracle bone script, a painting by early 20th century painter Qi Baishi, or a blue and white plum vase and become a "collector". But ultimately, who you are determines your thoughts and actions. That is, tuhao (土豪, the nouveau riche) turned collectors are still tuhao nonetheless - they live to make money. So, even if they become "lovers of culture", they have not forgotten about making money. As much as they are spending big bucks to gain cultural cred, they also have an economic goal in mind: they spend money to make even more money. For example, they spend millions of dollars on a painting by Qi Baishi so that they can earn tens of millions of dollars when they sell it a few years later after it has increased in value.

Culture for sale

And so, China suddenly became a nation of art collectors. With everybody well-fed and well-clothed, everyone started to comb the streets for antiques they could buy at a steal. Provision shops sold "Yuan dynasty" blue and white oil jars; old bookstores had copies of the "Song dynasty" block-printed edition of Du Fu's poetry collection (《杜工部集》) - thankfully not the Song dynasty block-printed edition of the Siku Quanshu (《四库全书》, or the Complete Library in Four Sections); waste paper recycling centres had "Chengxintang paper" (澄心堂纸, an exquisite paper produced during the Southern Tang dynasty); and second-hand clothing stores had Wu Zetian's pleated skirt!

Antique shops had even more impressive finds: there was the white silk cord that Yang Guifei used to hang herself at Mawei Courier Station (马嵬坡); the metal wok that Song poet Su Shi used to cook his famed Dongpo pork in Huangzhou; the sword that the Chongzhen Emperor used to kill his eldest daughter when the Ming dynasty was overthrown; and the "peach blossom fan" that the Ming dynasty courtesan Li Xiangjun vomited blood on. They had whatever one could think of and more. For example, there was the deified military general Guan Yu's legendary Green Dragon Crescent Blade; the Three Kingdom warlord Lü Bu's special halberd (方天画戟); monkey king Sun Wukong's magical Jingu Bang; the ink brush that the revered author Cao Xueqin used to write the classic Dream of the Red Chamber; and the cloak that the character Du Liniang from The Peony Pavilion《牡丹亭》wore when she toured the Peony Pavilion. In the sale of these items, it's often up to the buyer to believe if the objects are authentic. The seller states a price, and the buyer pays for it - it is all talk for talking's sake, and simply taken for what it's worth.

True collectors have a deep love for cultural artefacts because they understand the profound meaning that these objects hold and cannot bear to watch them disappear.

Clearly, the nation is jumping on the collectors' bandwagon. Some spend one million dollars on a blue and white basin, others splash three million dollars on a painting by Ming dynasty painter Tang Bohu, and all agree that they are good buys, leaving observers absolutely dumbfounded. And immediately the next buyer appears, offering five million dollars and even ten million dollars for these cultural artefacts, further driving up the hype. It is like playing a game of "pass the ball" - players pass around an unauthenticated cultural artefact and make huge profits out of it in the process of passing it around. Is this what a collector does? Of course not.

A true collector's passion

When it comes to collecting artefacts, one must first be passionate about passing down cultural traditions. There must be an understanding that a cultural artefact is an embodiment of cultural traditions and a tangible artistic representation of history and tradition that revives memories from a distant past. It has the ability to cut to the core of our deepest cultural identity.

True collectors have a deep love for cultural artefacts because they understand the profound meaning that these objects hold and cannot bear to watch them disappear. That is why they are willing to spend all that they have to preserve these civilisational gems for future generations to enjoy.

One of the most admirable and awe-inspiring collectors of the modern era is Zhang Boju. In his writings, he revealed that he was born in an era of chaos and did not study much. He fell in love with calligraphy and paintings when he was in his thirties and went to the extent of being saddled with debt in order to keep adding important works to his collection. He did not regret his decision even when people scorned him. After many years, he amassed an impressive collection of ancient Chinese art works and would admire them and use them to educate himself and cultivate a sense of appreciation for the arts. Indeed, collecting pieces of calligraphy and paintings by illustrious painters helps one to hone his appreciation for the arts. Admiring such pieces brings endless joy - it is a spiritual communication with the ancient people and even a communion with heaven and earth in the spiritual realm.

Zhang further said, "The things I collect need not be forever mine, but should forever remain in our land and be passed down from generation to generation." In the 1950s, Zhang donated the precious works that he collected throughout his lifetime to the country. They included no less than 30 national treasures, including:

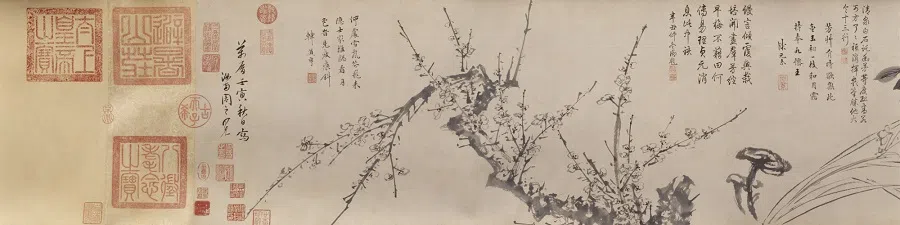

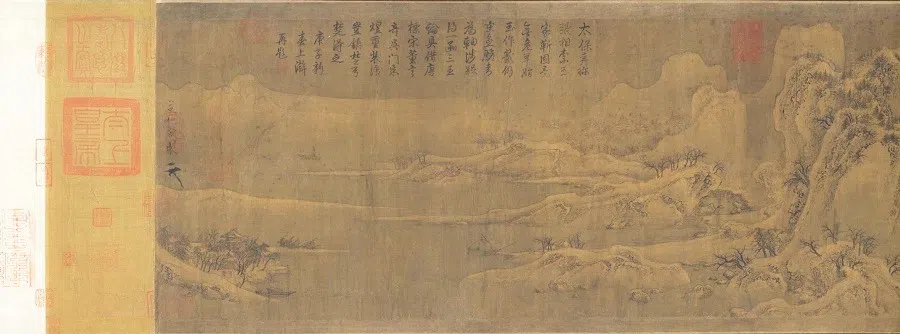

(1) Lu Ji's calligraphy Ping Fu Tie (《平复帖》, A Consoling Letter) of the Jin dynasty; (2) Zhan Ziqian's painting Youchun Tu (《游春图》, Spring Excursion) of the Sui dynasty; (3-4) Li Bai's calligraphy Shang Yangtai Tie (《上阳台帖》, Ascent to Yangtai Temple) and Du Mu's Zhang Haohao Shi (《张好好诗》Courtesan Zhang Haohao in Running Script) of the Tang dynasty; and (5-8) Emperor Huizong's painting Xuejiang guizhuo tu (《雪江归棹图》, Homeward Bound on a Snowy River), Fan Zhongyan's calligraphy Daofu Zan (《道服赞》, Encomium on Daoist Attire), Cai Xiang's poetry album Zishu Shi (《自书诗》, Personally Written Poetry), and Huang Tingjian's cursive script Zhu Shangzuo Tie (《诸上座帖》, The Host of Monastic Superiors ) of the Song dynasty.

This is a mark of great ambition and true selflessness.

More importantly, collecting cultural artefacts is a way for them to contribute to preserving exquisite art works and protecting these cultural gems from getting lost in the mayhem of the material world.

Over the past decades, I have gotten to know a few collectors who are of the same mind. They view collecting not for the sake of investment or making a profit but for the sake of one's hobby and to hone one's eye for beauty. More importantly, collecting cultural artefacts is a way for them to contribute to preserving exquisite art works and protecting these cultural gems from getting lost in the mayhem of the material world. This is then a collector worthy of our respect and of the name of a collector of cultural artefacts.