Chinese economics professor: Fathers are not inferior to mothers when it comes to parenting

Since my return to China early this year, I have been the apple of my little girl's eye. Even the important task of sending her to the youth activity centre for lessons was entrusted to me.

I was obviously flattered; I put down all the books I was reading, cancelled all my meetings and declined all dinner invitations. I brought her to class every weekend and mingled with the other parents at the centre.

I would say around 70% of the parents there were female. Of the 30% that were male, most of them obviously did not go there often. They only popped in now and then. Male parents like me who frequented the centre in the last two months and who were at ease chatting with female parents were few and far between.

So, should female parents always be the ones sending their kids for lessons?

This question could be easily answered in ancient China or even just forty, fifty years ago. One might say this has always been how human society divides tasks and shares the load; because the mother is better at caring for the child, she is naturally entrusted with sending the kid for classes.

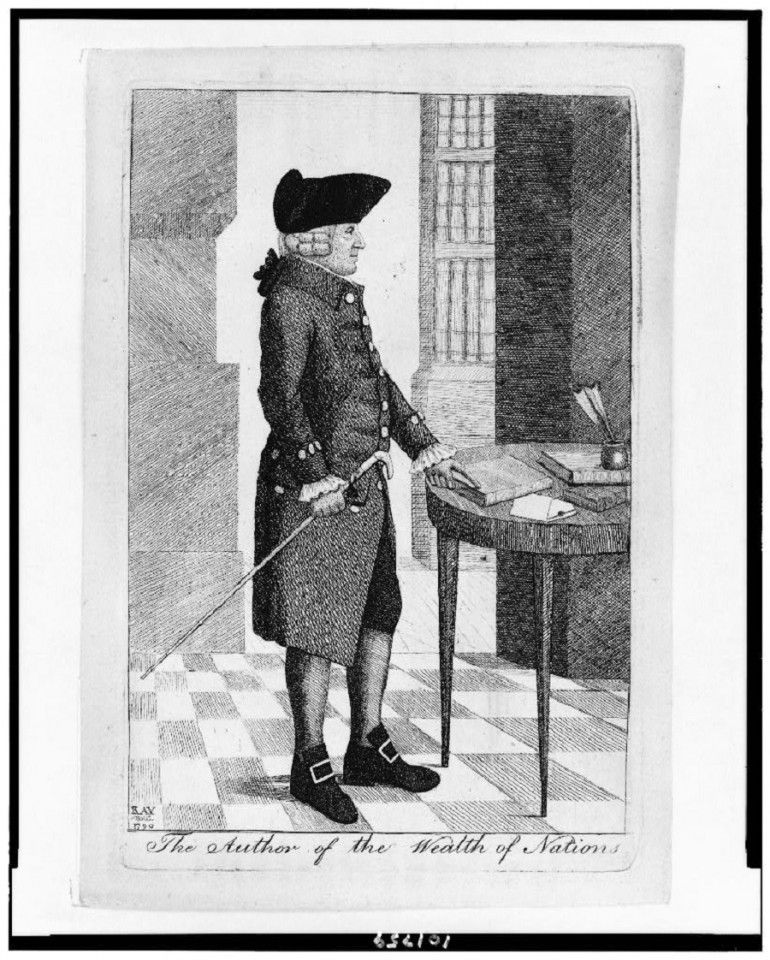

In 1776, renowned Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith, once a professor of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow, published his magnum opus An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. This key work laid the foundations of the economics discipline, which is why Smith is also called the "father of modern economics".

Division of labour for better productivity

Smith opened his book, commonly referred to by its short title The Wealth of Nations, with this central thesis: "The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which it is any where directed, or applied, seem to have been the effects of the division of labour."

Then, he gave the famous example of the pin maker.

Smith said that pin-making was a "very trifling manufacture" but one "in which the division of labour has been very often taken notice of". He explained that a workman not educated to this business, nor acquainted with the use of its machinery, could at the very best make one pin in a day, and certainly could not make 20. But as the business developed into "a peculiar trade that is divided into a number of branches", where "one man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head...", the business of making a pin became divided into about eighteen distinct operations, where each could be performed by distinct hands. As such, a team of ten persons could make 48000 pins in a day, with each person making 4800 pins daily!

Observably, such a division of labour greatly increases productivity and in turn, social wealth.

Early male-female division of labour gave rise to matrilineal societies

Man's earliest division of labour is perhaps that between man and woman.

In the Stone Age, the men of a tribe went out to hunt while the women gathered fruits and vegetables nearer to home, reared small animals, and took care of their household. But in a different era, the same division of labour gives rise to a different power structure. Why? Because when men and women's productivity level changes, the survival risks under such a division of labour start to change.

In a patrilineal society where men are deemed more productive, women either have to take the initiative or are forced to seek shelter under the protection of a man to survive.

When productivity was low, that is, when the men's hunting tools were ineffective, hunting was a high-risk activity. I am not referring to the activity being dangerous or life-threatening, but that the men might need to track the prey for several days and yet the hunt might still not be successful. If so, a tribe would not have a surplus of food supply, and the survival of the entire tribe would have been uncertain if hunting was its only mode of subsistence. While hunting skills that men developed were important, during that time and age, women's gathering skills could better guarantee the survival of the tribe. This is the reason why I believe matrilineal societies existed in history.

However, as humans continued to improve their hunting skills and as men continued to upgrade their hunting equipment, successful hunts became frequent and common, and food sources gradually stabilised. This meant men surpassed women in the race to provide sustenance for the body. Thus, human society transitioned from matrilineality to patrilineality, and we have what we call today a patriarchal society.

Productivity and patriarchy in the agricultural and industrial ages

In a patrilineal society where men are deemed more productive, women either have to take the initiative or are forced to seek shelter under the protection of a man to survive. However, if the men are unable to ensure that the children borne by the women are their own, they would perhaps be unwilling to take care of them or to invest human capital. This is detrimental to maintaining and raising the productivity of the entire tribe. Thus, the marriage system developed in which a man is allowed to have one or more wives, and the children that his wives give birth to can basically be regarded as his own, at least in a social sense. At the end of the day, it may be overboard to say that the marriage system is a type of property system, but we can at least say that the institution of marriage is a new form of human cooperation of a particular stage of productivity.

... females remain dominated by males and naturally take on the responsibility of raising children. That is because this task does not generate income, it naturally falls to family members with lower productivity.

In an agricultural society, men are physically stronger than women and are still the main labour force in farming, thus maintaining the characteristics of a patrilineal society. Hence, the so-called saying that "the father guides his sons and the husband guides his wife" (父为子纲,夫为妻纲) is actually still a type of power structure demonstrated by the division of labour between men and women under a particular stage of productivity.

Even in the industrial age dominated by the manufacturing industry, male labour is still the main source of household income. Thus, females remain dominated by males and naturally take on the responsibility of raising children. That is because this task does not generate income, it naturally falls to family members with lower productivity.

Women today benefitting from another role reversal?

However, the situation has drastically changed in modern society. The widespread use of machines in industries and the more precise division of labour in the modern economy have made collaboration more important. And women, having designated tasks for family members and coordinated various interpersonal engagements over the long course of history, have gained the upper hand whilst being in the weaker position. In today's society where office work has become the mainstream, women are showing strong advantages. The feminist movement thus began in developed western countries in the later half of the last century. Now, following the development of globalisation, the more free and prosperous the economy, the higher the status of women.

When I was little, my grandmother and mother were not allowed to eat at the dining table in the central hall whenever there were guests in the family.

I feel deeply about this as I lived for over 20 years in the northern regions of China, and for another 20 years in the southern regions later on.

I was born in an agricultural town in the north and later went to Hangzhou to study and work. When I was little, my grandmother and mother were not allowed to eat at the dining table in the central hall whenever there were guests in the family. They could only eat in the kitchen. Without a doubt, raising children was almost always the responsibility of the women in that era. Male parents mostly asked about how the children were doing occasionally and disciplined them if they did badly at exams. Of course, the men were in charge of earning a living. But when I arrived in Hangzhou, the status of women and men was the complete opposite of what it was like back in my hometown. In Hangzhou, women are much more well-respected by men than in the north.

Based on my chats with the other parents, if a family does not have to take care of the elderly at home, and if the income of the woman is higher than the man, the man would generally be the one accompanying his kids to their lessons. Of course, this sample size is not big enough and my conclusion may not be representative of the overall situation in Hangzhou, let alone society at large.

Co-parenting to win the child-raising war

However, objectively and generally speaking, in today's world, choosing a parent to accompany his or her children to their lessons is no longer dependent on their productivity levels. Today, raising children is like fighting a battle. To win the battle, we must fight together. In my family, my wife and I are just taking charge of different branches of the army. Specifically, I am responsible for manual labour like accompanying my children to their lessons, while my wife is responsible for the large amount of work that needs to be done on the smartphone because I have no clue how they are done. But I know that some families are the complete opposite of us.

From this perspective, those who think that women are naturally suited to educating children while men are unsuited to playing this role have actually forgotten that all this is simply the effect of the division of labour and not the cause of that division. Although males are indeed unable to give birth like the females - our biological make-up is different - males are certainly capable of doing all the remaining things such as feeding the child using milk bottles, changing their diapers, and accompanying them to their lessons. These tasks are not inherently different from the tasks of making bows and arrows and setting traps in primitive society, but the separation of duties is simply the effect of the division of labour in the name of survival.

If what Smith said is correct, then men are not necessarily inherently inferior to women in raising children, and neither should it be taken for granted that women should stay at home to raise and educate children.

In response to this, Smith wrote: "The difference of natural talents in different men is, in reality, much less than we are aware of; and the very different genius which appears to distinguish men of different professions, when grown up to maturity, is not upon many occasions so much the cause, as the effect of the division of labour."

For Smith, the difference between a learned philosopher and a common street porter was hardly about the former being gifted with intelligence, as some philosophers liked to say. In his view, this huge difference "seems to arise not so much from nature, as from habit, custom, and education", and is the result of putting into practice what one has learnt from different exchanges.

If what Smith said is correct, then men are not necessarily inherently inferior to women in raising children, and neither should it be taken for granted that women should stay at home to raise and educate children.

This article was first published in Chinese by Caixin Global as "神奇的生活经济学:养孩子这事跟分工有啥关系". Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

Related: Chinese women in the 21st century: Finding happiness and meaning in life | No bride price, no marriage in China | Chinese single women ponder love, marriage and freedom | A Chinese woman's status and the one-child policy | Woman traveller of the Qing dynasty Qian Shan Shili: Education is the bedrock of a nation