Chinese netizens lament barbarity of one-child policy era

The topic of "social reallocation" (社会调剂) or the practice of "excess" babies taken away from their parents in Guangxi province during the 1990s, has sparked heated discussion in China.

There are "reallocations" and "adjustments" in jobs, exams and funds, but many Chinese netizens are shocked that it could happen to humans too - and to newborn infants nonetheless.

'No records' of children being taken away

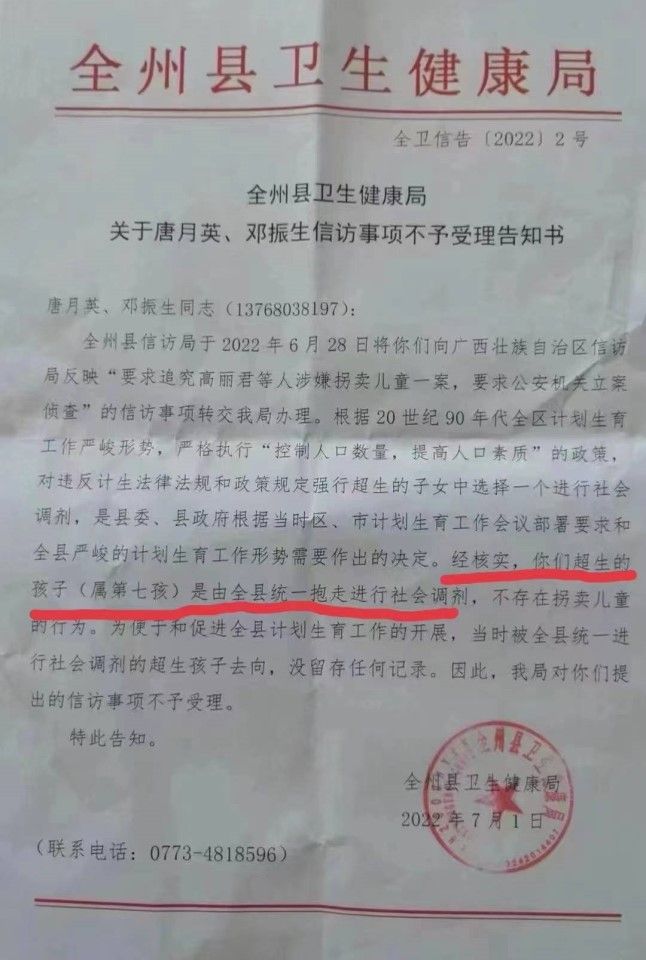

A document from the Quanzhou health bureau in Guilin city, Guangxi, rejecting an appeal from a couple whose son was kidnapped in the 1990s, was circulating online on 5 July and picked up by The Beijing News and Fujian Daily.

It showed that on 28 June, an appeal for the public security agency to investigate an alleged kidnapping was referred to the Quanzhou health bureau by the Quanzhou Bureau of Letters and Calls, which deals with complaint letters and calls submitted or made by individuals to the party or the state.

The couple, Deng Zhensheng and Tang Yueying, have four sons and three daughters. Their son and youngest child, Deng Xiaozhou, was taken away.

Xiaozhou's elder sister said that in August 1990, then head of the family planning office Gao Lijun and some others took away her brother, who was less than a year old, from their mother, and they have not seen Xiaozhou since.

In the document, the Quanzhou health bureau informed Deng and Tang that family planning work in the region during the 1990s was difficult, and the policy for population control and raising population quality had to be strictly implemented. Hence, it was mandatory for those who infringed the regulations to give up one of their "excess" children for "social reallocation".

The document also said that at that time, to facilitate and encourage family planning efforts, no records of these reallocated children were kept. Hence, the health bureau "would not be acting on the appeal".

The health bureau's response sparked an outcry, with one netizen asking, "How is this different from abduction and trafficking?"

In the face of public outcry, Guilin authorities organised a working group to investigate in Quanzhou. The health bureau's director and deputy director, along with other personnel involved in the matter, have been suspended.

Not an isolated case

Judging by the document from the Quanzhou health bureau, this was not an isolated case of "social reallocation". There have been similar cases in other Chinese provinces.

In May 2014, China Youth Daily published a report titled "'Reallocated' for 23 years" (《被"调剂"了23年的人生》) on Xie Xianmei, a young woman from Dazhou city in Sichuan province, and her search for her birth parents.

After finding her birth mother through DNA testing, Xie pieced together what happened to her with recollections from her birth mother and adoptive father, Xie Yuncai, as well as family planning officials.

Like the Quanzhou case, her birth parents could not afford to pay the fine, and Xie Xianmei was taken away by the family planning office of Nanwai town, and adopted by Xie Yuncai, with a fee of 200 RMB (US$30) in 1991. This was no small sum at the time, and her adoptive father sold two pigs to get the money.

Xie Yuncai recalled that family planning was very strict that year in Dazhou's rural areas, and the family planning office even set up a dedicated room for women who returned to the city after giving birth elsewhere.

According to People.cn, on 12 May 1991, a "decision on strengthening family planning and strict control on population growth" was released, where family planning and population planning would be made a key performance indicator for party committees and government leadership cadres.

Li Benyou, former director of the family planning office for Nanwai town, told Xie Xianmei, "I had no choice then, the higher-ups were pressing hard."

... the family planning office cadres could receive at least 1,000 RMB for each child sent to the welfare home, while overseas adoptive families usually paid US$3,000 for a Chinese orphan adopted through the relevant channels.

'Abandoned' babies an industrial chain?

If fines for "excess" births and adoption fees were "normal procedures", what happened in Shaoyang city in Hunan province must be considered appalling.

Caixin's New Century (新世纪) magazine ran a cover story in May 2011 titled "Abandoned Shao Babies" (邵氏"弃儿"), which sparked a major outcry.

"Abandoned Shao babies" referred to the infants and young children forcibly taken by family planning authorities in Longhui county, Shaoyang city in Hunan province. A dozen children from farming families were sent to welfare homes and given the surname "Shao" (after Shaoyang). Most were then moved into adoption channels.

Caixin reported that the head of a welfare home in Shaoyang confirmed that between 2002 and 2005, they received 13 babies from the civil affairs and family planning offices of Gaoping city, Longhui county.

An informed source told the media that the family planning office cadres could receive at least 1,000 RMB for each child sent to the welfare home, while overseas adoptive families usually paid US$3,000 for a Chinese orphan adopted through the relevant channels.

After the report was published, the local government launched a joint investigation. Five months later, in conflict with what the villagers had told the reporters, the investigation stated that there was no child trafficking involved as most of the babies were abandoned.

Many years later, the truth about the "abandoned Shao babies" remains a mystery, but some of the children who were adopted by families overseas have returned to Shaoyang in search of their birth parents.

With the help of US media, Zeng Youdong, a local farmer who lost one of his twin daughters, finally reunited with his long-lost daughter of 17 years in 2019 and spent the Spring Festival together as a family in their Shaoyang home.

Yang Libing, another interviewee in the report, learned from volunteers that his daughter may have been adopted by a family from Illinois, US, but that was as much information as he could gather.

Decades-old one-child policy

China's family planning policies have evolved over time. The most prominent policy was the one-child policy introduced in 1979 where couples were allowed to have only one child. This policy later became China's basic national policy.

Specific measures of the one-child policy include fines for having more than one child and compulsory sterilisation, which were implemented by various local family planning offices. In practice, however, harsher measures were taken as a result of the pressure from the higher-ups or the benefits that could be reaped.

Perhaps most people still vividly remember the family planning slogans of that era: "Rather bleed a river than have an extra child" (宁可血流成河,不准超生一个); "Your house will collapse if you fail to sterilise" (该扎不扎,房倒屋塌); "You can run away today but your property will be gone tomorrow" (今天逃避外出,明天财产全无). These intimidating slogans were not just for show - some families had indeed fallen apart because they had more than one child.

Entering the internet era, the most shocking event was perhaps the forced abortion of a seven-month-old foetus. In June 2012, Feng Jianmei, a second-time mother from Shaanxi was forced to abort her seven-month-old female foetus as she was unable to pay the fine for having an extra child. The news sent shockwaves across China and was widely reported by international media.

The Quanzhou social reallocation case has also put a spotlight on the historical issues remnant of the one-child policy era.

Following China's shrinking and ageing population, major changes have been made to the country's family planning policies in recent years. In November 2013, China relaxed the one-child policy and allowed couples to have two children if one of the parents was an only child. In January 2016, all couples were allowed to have two children, and as of May 2021, couples are now allowed to have three children.

"Furthermore, treating children like transferable objects destroyed basic ethics and was a criminal act. - Zhao Hong, a professor at the China University of Political Science and Law

Individual lives and history cannot be ignored

In response to the Quanzhou social reallocation uproar, on 5 July The Economic Observer published a commentary by Zhao Hong, a professor at the China University of Political Science and Law.

Zhao criticised the local government from the perspective of the rule of law and human relations. He said that taking away excess children from families for social reallocation was an act worse than the illegal disposal of the property (such as houses and foodstuffs) of these families. Furthermore, treating children like transferable objects destroyed basic ethics and was a criminal act. The officials and law enforcers involved had abused power and committed the crimes of child abduction and child trafficking.

Arguments that these were "standardised social reallocation" or that "no records have been kept" were just not acceptable. - Commentary by Ding Hui published in The Beijing News

The Beijing News also published a commentary by Ding Hui which said that these children could not have vanished into thin air and that the related local government departments should make amends as soon as possible.

The article added that children were not commodities or resources that could be freely allocated by others. Moreover, the term "social reallocation" defied common sense and breached the ethical bottom line. Arguments that these were "standardised social reallocation" or that "no records have been kept" were just not acceptable.

Former Global Times editor-in-chief Hu Xijin talked about the historical evaluation of family planning policies and wrote that family planning was a demographic revolution conducted under the conditions of the times. In the process, there was certainly reluctance and suffering for individuals and families.

It is important to make amends for old tragedies, as a society's attitude towards individual lives and history would shape its future and what it will become.

Still fresh in people's minds, the evaluations have been complex, and include humanitarian concerns and anxiety over a rapidly ageing population. It is expected to continue for years and generations until a relatively stable historical perspective is formed.

He also said that some old problems have become today's tragic realities that may not have good solutions, and if grassroots officials fail to resolve these with the right attitude, a new public opinion and perspective with the potential to trigger public rage could quickly form.

As Chinese society develops, thoughts on population and human rights issues have also evolved. While history will certainly assess the decades-long basic national policy, the sufferings and trauma of each family and individual in the process should not be ignored.

It is important to make amends for old tragedies, as a society's attitude towards individual lives and history would shape its future and what it will become.

Related: A Chinese woman's status and the one-child policy | Why Chinese women are unwilling to give birth | 'The world has abandoned me': Chinese women married into slavery? | China wants to reverse its high abortion rate with pro-birth policies, and young women are not happy | A Singaporean in China: Can there be justice for trafficked women sold as wives? | Gender equality: The solution to China's declining birth rate