Chinese artist Zeng Fanzhi: Constructing a visual language all his own

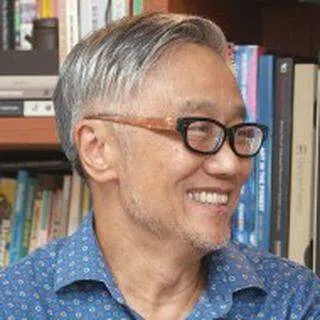

Former director of the Singapore Art Museum Kwok Kian Chow shares his thoughts on reencountering the works of Chinese artist Zeng Fanzhi at the Museum of Art Pudong, Shanghai.

(All photos provided by Kwok Kian Chow unless otherwise stated.)

Conlang is an uncommon word. It means "constructed language", as opposed to most languages that evolved naturally over a long period of time. Hence, a person who invents a language is called a conlanger.

In A Clockwork Orange, the linguist and author Anthony Burgess famously created the conlang "Nadsat", a fictional argot used by a teen subculture. Nadsat was supposed to be used only in the fictional world, but with the popularity of the film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange by Stanley Kubrick, Nadsat found its way into everyday youth language. It thus evolved from a conlang to be a part of natural language.

The conlanger Zeng Fanzhi

In the visual arts, artists have likewise created unique personal painting styles. Such unique styles are not usually compared to a language which has a structure, grammar, syntax, etc.

A painting style has a set of characteristic expressions, palettes and formal qualities. However, when an artist systematically constructs a structural approach to painting in a "linguistic" mode, he can be thought of as a conlanger, thinking not just about the subject matter, underlying emotions, and expressive quality but transcending all that to arrive at a way of painting that is as systematic as a language.

Zeng can draw the viewers into his world of pure art language, like grammar and phraseology, before the meaning of the artwork is considered.

Just as how a language evolves over time, the approach is developmental, systemic, and consistent with a deep sense of advancement over a longer time period. I think of Zeng Fanzhi as such an artist. Zeng can draw the viewers into his world of pure art language, like grammar and phraseology, before the meaning of the artwork is considered.

Only one constant: a unique visual language

I recently visited the exhibition entitled "Zeng Fanzhi Old and New: Paintings 1988-2003" at the Museum of Art Pudong, Shanghai (the exhibition is from 27 Sep 2023 to 8 Mar 2024).

Soon after I entered the gallery, I stood before a familiar work, asking myself the exact same question from my first encounter with the work 16 years ago in 2007: who is she/they? She walked away from me again, leaving me to wonder who she might be, where she was heading, and what the story of her walking alone on this forest pathway shone by bright lights whose source could not be explained.

We met for the first time when Zeng Fanzhi had his first museum solo exhibition outside China. I was privileged to be the co-curator with Chow Yian Ping for "Zeng Fanzhi: Idealism" which was presented at the Singapore Art Museum in 2007.

The same rush of puzzlement and awkward emotions in my re-encounter returned in full force. Am I to experience the painting as an energy field, considering the intensity of the crisscrossing brushstrokes amid the vigorous colour pigments? If yes, what is she doing there?

By 2007, Zeng had already concluded his earlier Face Mask series, for which he is best recognised by many art lovers. To entitle his "walking away" piece, also a figurative work, Abstract Landscapes - Night (2005), was another puzzlement.

This suggests that there has been one other dimension, or a constant, in Zeng's new "abstract landscape" works since the mid-2000s - that constant is the language.

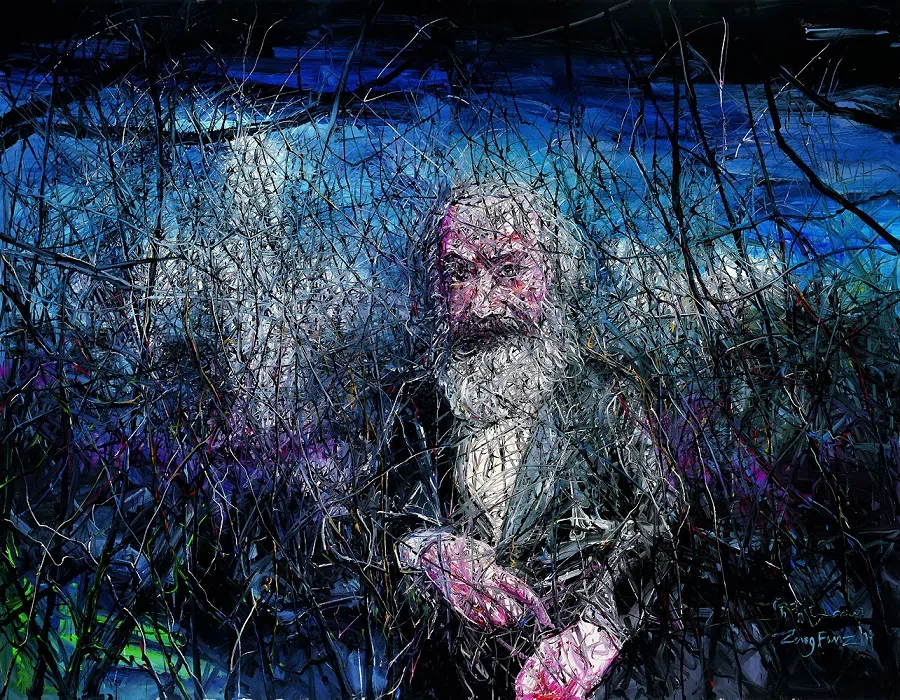

At the 2007 Singapore Art Museum exhibition, portraits in a similar mode of brushwork in the Great Men series including Karl Marx - He is from Germany (2007) were exhibited. Marx's portrait was also chosen as the main image for exhibition publicities.

While Abstract Landscapes - Night (2005) and Karl Marx - He is from Germany (2007) differed in the figure's identity: one unknown while the other a towering historical figure, the two paintings converged in Zeng's brushwork and painterly expression.

This suggests that there has been one other dimension, or a constant, in Zeng's new "abstract landscape" works since the mid-2000s - that constant is the language. Beyond that, the subject matter seems to have operated on separate and arguably less significant registers in Zeng Fanzhi's work.

I suggest understanding this "strange feeling" of Zeng as a painting language which may not be broken down into figurative versus abstraction, subject versus the lack of which, or even emotion versus the absence of which.

Capturing a 'strange feeling'

Exploring the Old and New exhibition further, I soon realised how this constant has evolved over the past sixteen years in great brilliance.

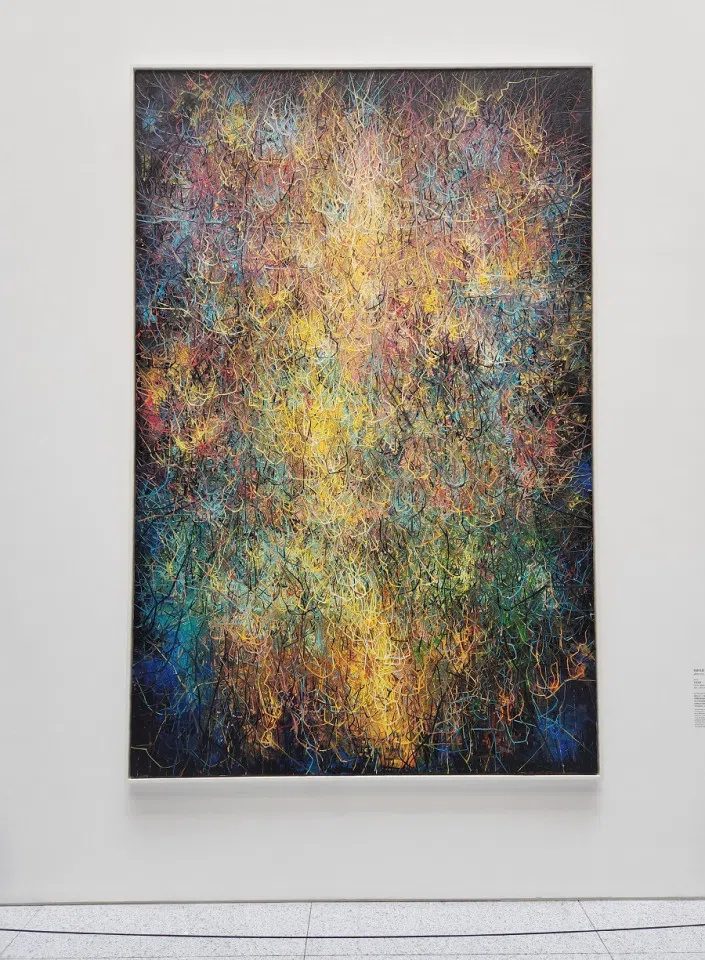

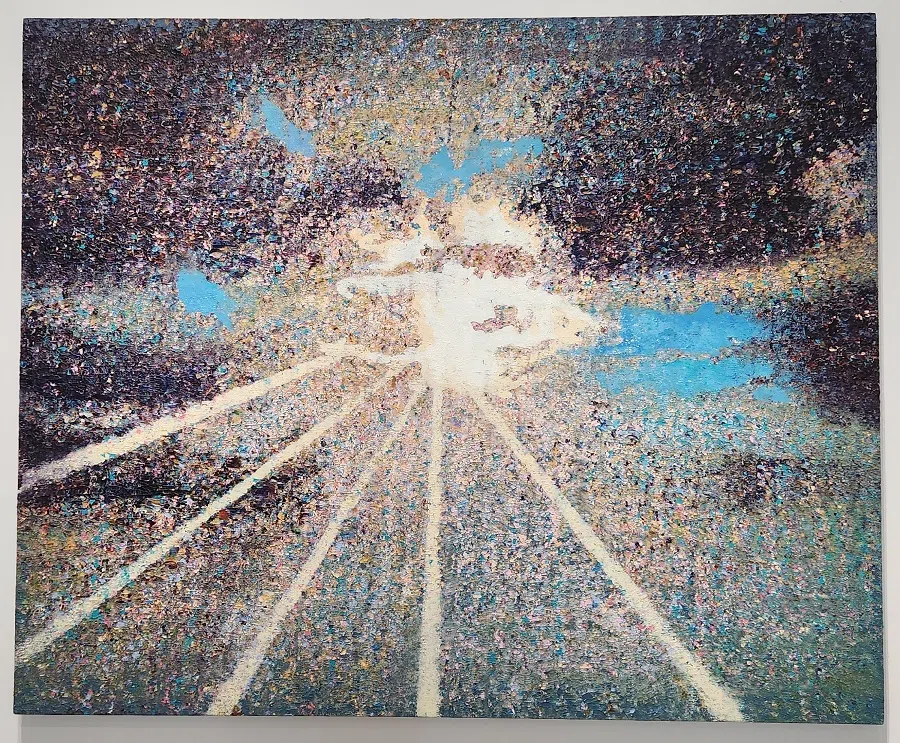

Zeng's energetic brushwork done in an "abstract landscape" manner, an emphasis on the painting language itself, unfolded in a new incandescence as seen in works such as the vast 7 by 4-metre Abstract Landscapes - Blue (2015) and another enormous work, Abstract Landscapes - Untitled (2019).

Zeng's Abstract Landscapes series has been a key to understanding Zeng's art since the mid-2000s, or to me personally, since the Singapore Art Museum exhibition in 2007. The encounter with Zeng's expanded oeuvre over sixteen years in a single exhibition at the Museum of Art Pudong further unveiled Zeng's artwork to me.

"In all my creations," Zeng once noted, "whether I move from abstraction to representation or portraits, I constantly need that sense of breaking new ground. I like to capture that strange feeling. I love capturing these coincidences. So my paintings have no boundaries. I don't confine myself to any boundaries."

I suggest understanding this "strange feeling" of Zeng as a painting language which may not be broken down into figurative versus abstraction, subject versus the lack of which, or even emotion versus the absence of which.

For Zeng, a painting is not just limited to its title and subject matter. It also possesses an energy field that exists beyond the subject, almost as a parallel existence. The Old and New exhibition has helped me understand that this energy field has had its trajectory over the years.

In the "Zeng Fanzhi: Idealism" curatorial text, I tried to explain how Zeng combined expressionistic impulses through gestural strokes imploring intensive emotive responses.

Yet, the Abstract Landscapes - Night (2005) work was "realistic" in a figurative and even narrative sense. Who the walking away figure is may never be known, but what responses Abstract Landscapes - Night (2005) induced became a reality or "realism" itself.

The Old and New exhibition, featuring some 60 works, is presented in six sections loosely serially and thematically organised (such as Portraits and Still Lifes), taking space, scale, and illumination into consideration.

In the Singapore Art Museum exhibition, Zeng was already deeply concerned about the environment of the presentation: "The gallery spaces at the Singapore Art Museum were unique to me in that they resonate with history as they were once classrooms of a school. I feel that as an institution of learning, the notions of idealism must have been held in high esteem by the teachers and students of the school working towards a future that would be filled with both ups and downs. But despite this uncertainty, idealism was still a spark that fired many imaginations. These new works I created for the exhibition is [sic] an expression of myself towards the gallery spaces at the Singapore Art Museum."

While the crisscrossing brush strokes formed the syntax of the Abstract Landscapes series, the architectonic layering of micro-colour patches optimised the high luminosity of the Sparking Paintings series.

A deep sense of mysticism

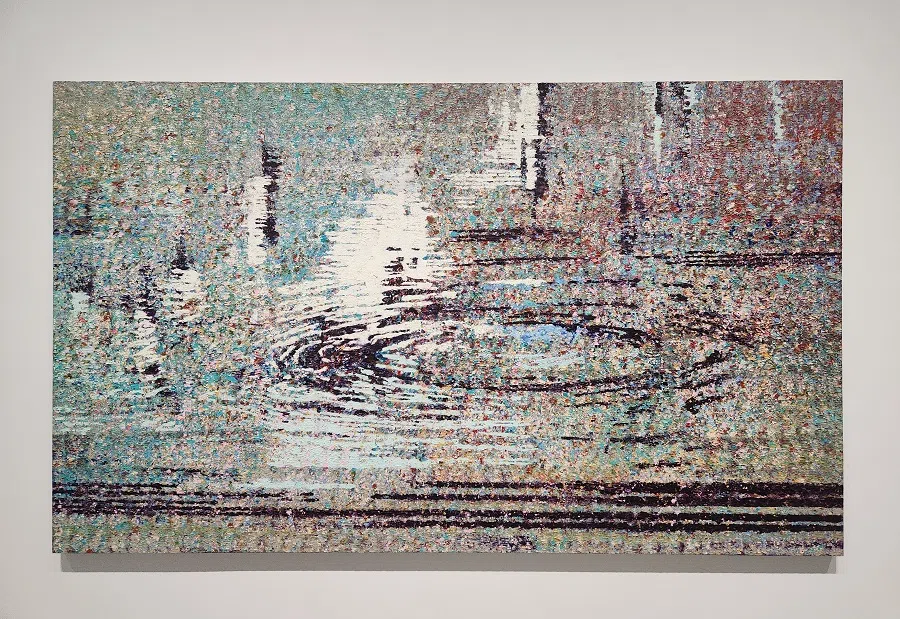

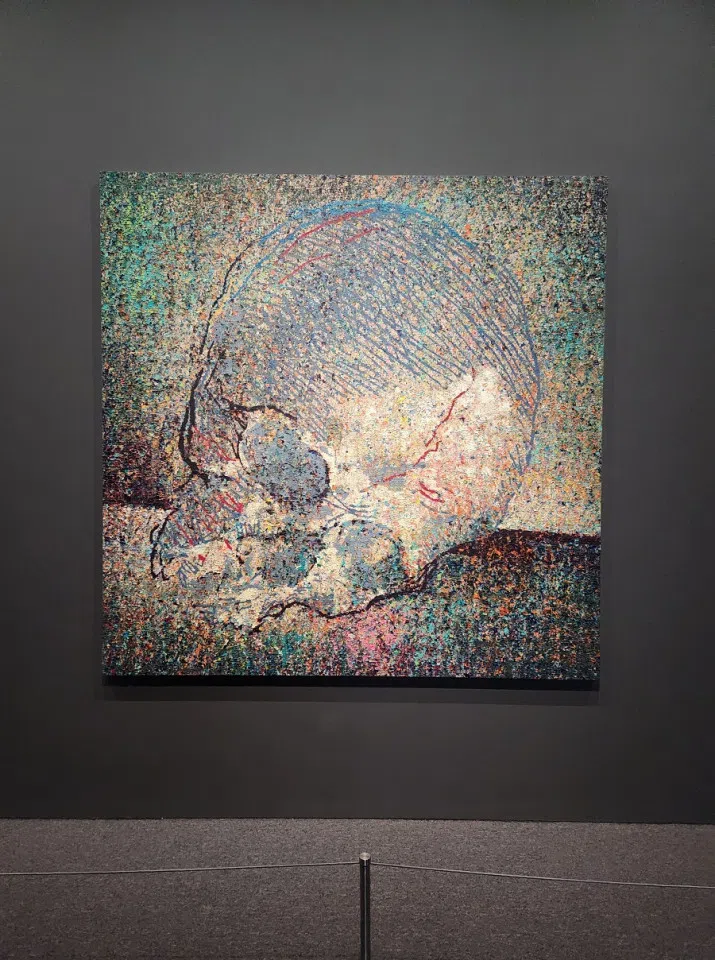

Zeng Fanzhi's new Sparkling Paintings series works are presented parallel to the newer works in the Abstract Landscapes series and overlap in the language theme I propose.

The Sparkling Paintings series (created since 2019) could be deemed an extension and a dimension of the Abstract Landscapes series. A new theme, contemplation, is introduced in the Museum of Art Pudong exhibition, and a Zeng video work YÓU 游 Project is presented at this point (section before the Monumentals final section).

Both of these final sections heightened the Sparkling Paintings and gallery lumination sequences with respect to the spaces, emphasising contemplation as a conceptual theme.

While the crisscrossing brush strokes formed the syntax of the Abstract Landscapes series, the architectonic layering of micro-colour patches optimised the high luminosity of the Sparking Paintings series.

Contemplation may mean looking at something and thinking deeply about it, or a mental process that may or may not involve visual imaging. Both of the above have a close relation to language.

Journeying from Abstract Landscapes to Sparking Paintings, a linguistic structure with a "grammar" of brushwork builds up toward a heightened contemplative visual field, amounting to partaking in Zeng's project as a conlanger.

There is a deep sense of mysticism in the Sparking Paintings series as if words in a language must now be elevated to pure light and colour to get any message across.

The exhibition wall text highlights that Zeng Fanzhi, like Cézanne, Picasso, Gerhard Richter and others, is deeply interested in the 17th-century vanitas paintings (still lifes including symbolic objects).

With the Sparking Paintings series, I also ended up wondering if the endpoint of a language is a state of wordlessness.

I saw this especially in Sparkling Paintings - Skull III.

In going through the Old and New exhibition, I asked if the task of a conlanger is to systematically invent a language and to launch it as a part of natural language, as Zeng Fanzhi has created his own language of painting, and shared this at large in the explorations into the purposes and possibilities of painting?

With the Sparking Paintings series, I also ended up wondering if the endpoint of a language is a state of wordlessness.