An exceptional thread of guqin heritage

Academic Lian-Hee Wee shares how the delicate craft of making and repairing ancient guqins was passed down to Master Choi Chang Sau in Hong Kong, and lives on through his disciples at the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society.

(Photos: Lian-Hee Wee)

The now economic juggernaut that is China, has, in the last two decades, put much effort into recovering and rediscovering threads of heritage broken by volleys of historical misfortunes. This is a brief story of one exceptional thread that survived untouched because it reached out to Hong Kong at an important historical juncture.

Through touch, one knows how the instrument would go with the player’s hands, and how well sounds resonate as wood metamorphosises into the instrument.

In the late 1940s, Xu Wenjing (徐文鏡) arrived at the Fragrant Harbour. While others had come to escape war and prosecution, Xu’s trip was also motivated by medical needs for his eyes. Xu was an accomplished literato, a kind of renaissance man in traditional Chinese scholarship. Not only did he author one of the most authoritative tomes on ancient Chinese scripts, the 《古籀汇编》 (Guzhouhuibian), he also concocted the best of the red Chinese seal paste, the 紫泥山馆印泥 (zinishanguan yinni).

Among Xu’s talents were the playing and making of the guqin (古琴), which he inherited through a long line of masters of the 浙 (Zhe) school — the guqin being the erstwhile instrument of traditional Chinese cultivation, listed first among the four arts (guqin, weiqi, calligraphy and painting).

The art of repairing a delicate construction

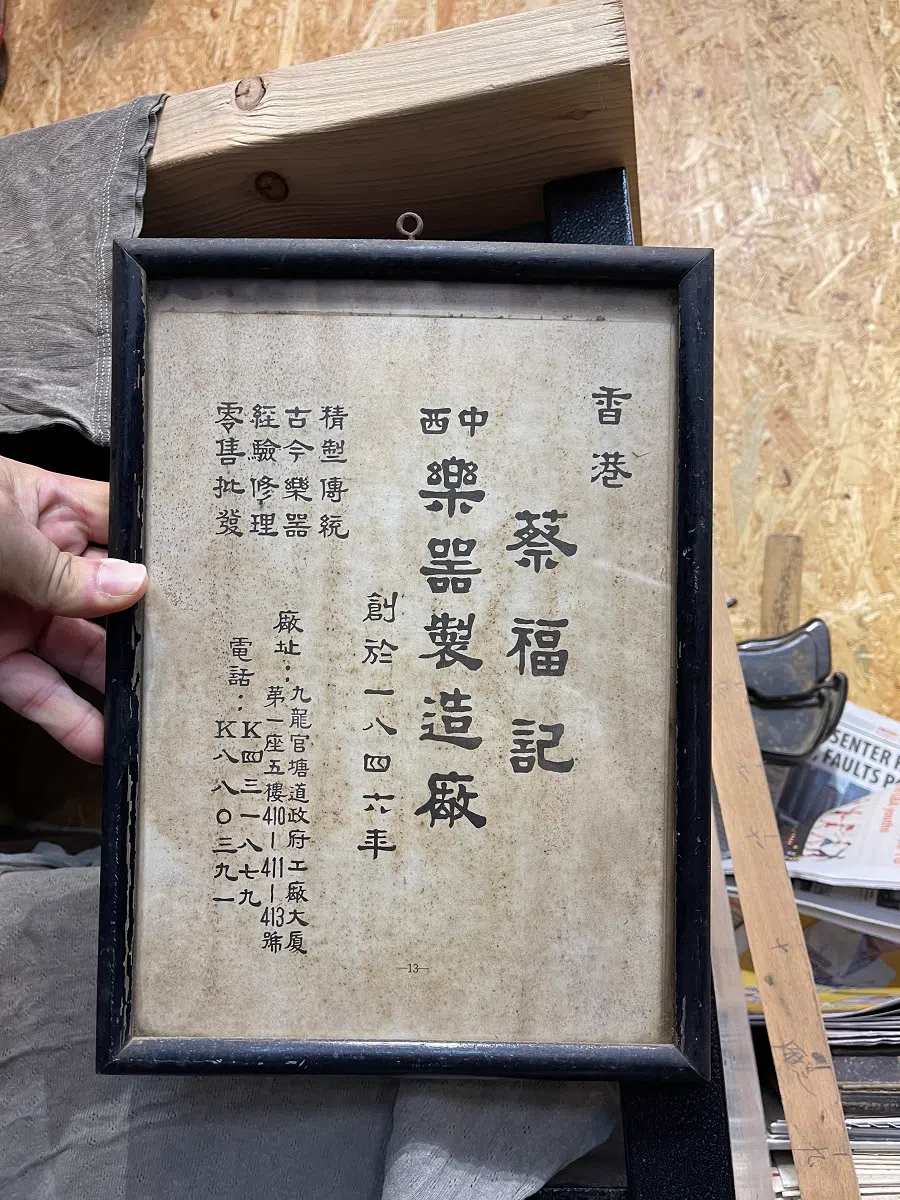

Failing eyesight compelled Xu to seek help with inevitable repairs of his guqins when he was in Hong Kong. The Choi Fook Kee Musical Instrument Factory (蔡福記中西樂器廠), hereafter CFK, was the most obvious choice. CFK, founded in 1846 in Chaozhou, has been established in Hong Kong since 1904. At least up until the 1980s, CFK produced almost all the Chinese musical instruments used in Hong Kong and made guitars that sold as far as Germany, alongside violins that were exported to the US.

In the 1950s, when Xu brought his qin to CFK, none of the craftsmen there had intimate knowledge of the qin’s construction. All were suitably impressed as Xu gave his precise technical instructions for the repairs. Young Choi Chang Sau (蔡昌壽), then helping out at his father’s factory, was smitten. Although eager to find someone to pass on his skills, Xu was also strict, and carefully tested Choi for some years before accepting him as a disciple.

Xu eventually lost his sight, but was nonetheless uncompromising in checking his understudy’s progress. In doing so, the master demonstrated one of the great mysteries in instrument artisanry: the touch. Through touch, one knows how the instrument would go with the player’s hands, and how well sounds resonate as wood metamorphosises into the instrument.

In time, Xu and Choi collaborated to make a few qins together. After his master’s passing, Choi became the only person in Hong Kong with intimate knowledge on the repair and maintenance of antique qins. Choi’s skills and dedication towards qin-making endeared him to other masters of Chinese art and scholarship. Indeed, Master Choi’s friends included the great academician Jao Tsung-yi, the renowned Lingnan school painter Chao Shao-an, among other notables.

... more urgently, Master Choi was the only link left from an unbroken thread of qin artisanry.

To whom antique qins were entrusted

Along with migration out of mainland China through a tumultuous era came many of the finest antique guqins. Many would find their way to Master Choi for repairs. In fact, as late as 2023, the present author was fortunate enough to help with the restringing of a guqin dating to the Dakang (大康) reign-period (1075-1085) of the Liao dynasty. The instrument had belonged to Wong Tok Sau (黃篤修 1914-1978), who chaired the Amoy Food Company in Hong Kong that produces condiments familiar to Singaporeans.

Despite many dignified associations, there was hardly a market for guqins in those days. The subdued and delicate timbres of the guqin did not resonate with most who would learn a Chinese musical instrument. But Master Choi persevered. The guqin symbolised and embodied the most noble and timeless of Chinese civilisation.

In 1992, cancer struck. Master Choi survived, but felt it no longer viable to continue the business at CFK. In any case, mass production of musical instruments in mainland China proved impossible to compete against. As he contemplated retirement, a group of guqin masters in Hong Kong proposed that he pass on his art of guqin making. Classes would mean income, and more urgently, Master Choi was the only link left from an unbroken thread of qin artisanry.

These amateur enthusiasts, like the traditional literati before them, are strands of silk that extend from a long and tested tradition.

Labour of love

CFK’s premises became the studio for the first guqin workshops that ran in 1993. By 2011, the Choi Chang Sau (CCS) Qin Making Society was established. In 2014, the society received protection at the national level as an Intangible Cultural Heritage unit with Master Choi at its helm as a national-level grandmaster. Master Choi, now in his 90s, has retired fully after appointing six among his 50 odd disciples to be instructors to pass on the art faithfully.

Master Choi has strict rules. Applicants must have learnt how to play the guqin before they would be accepted as students. To complete the first guqin, a student will take about 18 to 24 months. Everything is done from scratch with all parts handmade. Some electronic tools like electric hand-drills or a lathe are allowed, but generally the crafting adheres to tradition as much as possible. Even adhesives are self-made from a mixture of flour and natural tree lacquer, or else prepared into hide glue using pig’s skin bought from the wet market.

Every step requires patience and perseverance found only in those truly in love with the guqin. Since natural lacquer is a strong allergen, that too represents an obstacle for applicants who must endure intense itches. After completion of the first guqin, the student may then be recommended for membership into the society. As encouragement, Master Choi recognises a student to have graduated after completing three guqins. At present, there are about a dozen active apprentices who have chosen to continue their study with Master Choi even after many years of apprenticeship, and already having completed quite a number of guqins.

Stringent requirements keep out many, but the few who persist would have very real commitments. Guqins made at the society are not for sale and have never been so. Thus, the commercial world may not sway these people from their art. There is nothing in the world of fashion or economics that would adulterate their aesthetics. The authorities of conservatories or academia cannot consume them, but instead have referred and deferred to them as living fossils of humanity’s cultivated past.

These amateur enthusiasts, like the traditional literati before them, are strands of silk that extend from a long and tested tradition. If you ever have the chance, play on one of their instruments, and compare that experience with playing on finer guqins available commercially. For want of a better analogy, it would be like comparing your grandmother’s laksa with that from a Michelin hotel. The latter is good, is art, but also quite something else.

(NB: Master Choi no longer entertains visitors and does not accept interviews. The CCS Qin Making Society currently accepts students, and retains the same rules set by Master Choi. The current instructors at the society are Kelwin Kwan, Tong Wan Hoi, Ho Chun Wah, Loo Sze Yuen, Li Fei and the author.)

Acknowledgement: The CCS Qin Making Society for information and photos. Ng Kum Hoon for reading and commenting on an initial draft.