Hong Kong graffiti: Art, vent or therapy

Hong Kong graffiti in the last few decades have been largely disciplined, and have embellished many dilapidated walls, enlivening otherwise boring surfaces, says academic Lian-Hee Wee.

(Photos: Lian-Hee Wee)

Most people think of vandalism when they hear “graffiti”. This comes in part from the fact that graffiti is seen only in places where permission is ostensibly lacking, and in part from how some practitioners require illegality as a feature of their activity.

While some cities (e.g. Shanghai) have “free [legal] walls”, Hong Kong outlaws graffiti, imposing fines and community service orders for this “criminal offence”. The graffiti world in Hong Kong abides by the following “rules”, largely adopted from the West:

#1. Graffiti practitioners are “writers”

#2. Tags 🡪 throw-ups 🡪 pieces and collaborations (collabs)

#3. Be respectful

The rules give graffiti a mafia-like sheen, although in reality practitioners are very gentle and civil. I have interviewed quite a number in Hong Kong, all of whom exude high aesthetic sophistication and are deeply philosophically reflective.

They are very shy. I have not been able to learn their real names, addressing each other only with monikers. At the same time, they are warm and welcoming, sharing knowledge freely and candidly.

... graffiti are words and symbols embodying a message, hence different from a pictorial mural. A “tag” is the signature of a writer, usually in one colour.

Following the rules without following the rules

By #1, graffiti are words and symbols embodying a message, hence different from a pictorial mural. A “tag” is the signature of a writer, usually in one colour. It may be done with a spray can, a drip-stick or stickers. Newcomers should start by putting up tags until they become accepted as “known” personae.

A throw-up is a tag done with two colours (Figure 3). A piece has more, is usually larger, and should be done only by writers already accepted by the graffiti community. Writers seem to know intuitively when they are accepted. Collabs are pieces done by a few writers together who may or may not be a team.

It is okay to write over a tag with a throw-up, which may in turn, be overwritten by a piece. Overwriting must be complete. Violation of #2 is regarded as disrespectful (#3) and incurs censure, ironically, in the form of vandalism (Figure 4).

Uncoincidentally, 2019 saw a sudden increase in the number of graffiti writers in Hong Kong. These younger practitioners have a laxer interpretation of what counts as “writing”.

The medium is the message

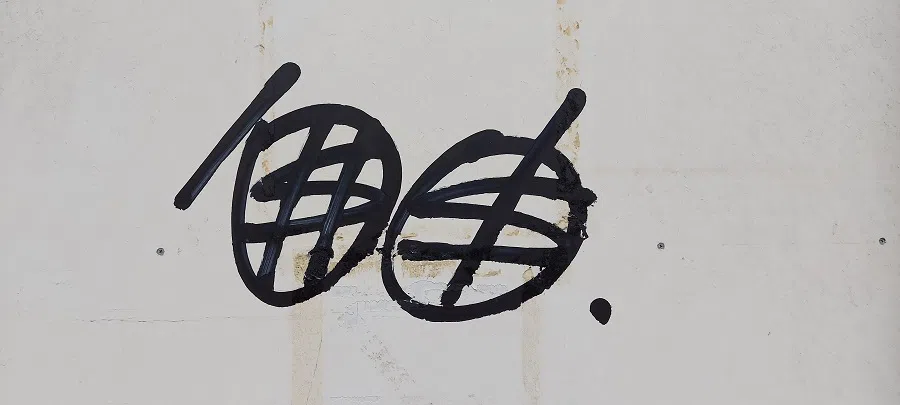

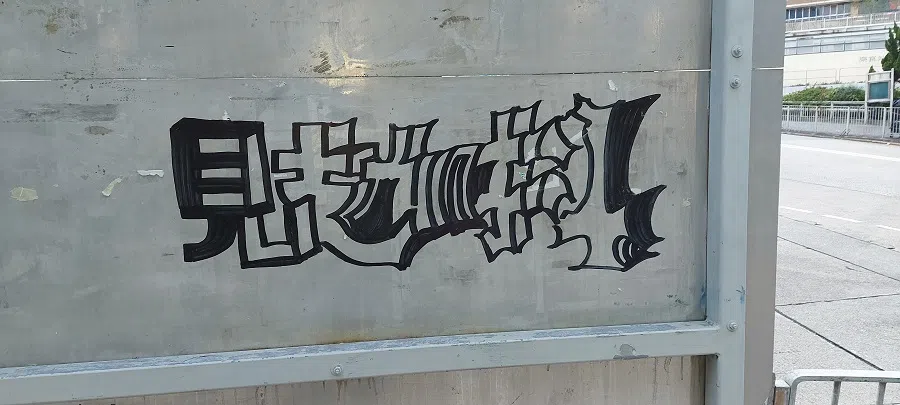

Uncoincidentally, 2019 saw a sudden increase in the number of graffiti writers in Hong Kong. These younger practitioners have a laxer interpretation of what counts as “writing”. Compare Figure 6, by Bob (~20 years old) and Figure 7 by Edge, who is much older. Edge’s piece is actually made up of letters, but Bob’s is much more stylised and abstract.

To the uninitiated, the concept of writing as the main graffiti activity is mind-boggling because to the untrained eye, graffiti appears to be instantiations of street art. Consider Figure 8, for instance. The whole piece is the Chinese character 爆 (bao, explosion) sandwiched by a bomb-face on the left, and a bundle of dynamite sticks on the right. Figure 9 offers another example that looks more like a picture mural than writing.

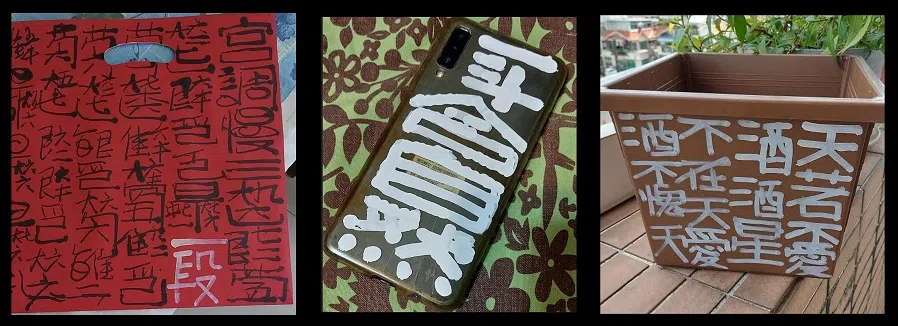

Graffiti writers interviewed explained that an essential part of their activity is to convey a message. For instance, Figure 10 shows a progressively unhappier smoking face. The astute reader would recognise the face to be the Chinese character 酒 “wine”. What the message is may be hard to articulate, but there is clearly one.

Freedom of expression a hot-button issue

However, messages can be sensitive. Around November 2023, “Mick” was arrested for spraying the graffito in Figure 11 in some 4000 places over a few months. Graffiti arrests have never found attention in the media, but this coverage was very high profile, indicative of how jumpy Hong Kongers are about freedom of expression and creativity. Just as I was writing this in end-June, the media reported an arrest of a 29-year-old for three counts of seditious graffiti on the seat back of a bus.

The court gave Mick a community service order and a standard fine. After all, “freedom” is one of the twelve core socialist values articulated by Xi Jinping.

Focusing on how graffiti always involves a message, one can see an interesting shift from the old kinds of advertising graffiti (Figure 12) to more recent ones that have a greater therapeutic mission (Figures 11 and 13).

The recent years have seen a lot more of these “encouragement” and “therapeutic” messages, often written in Chinese, particularly Cantonese.

Graffiti of encouragement

The world was suffering from Covid in 2020, and for Hong Kong it abutted the end of the social unrests that festered through most of 2019. These messages may have been vented by those who felt something had been lost. Equally likely, the graffiti may have been benign ways towards healing, privately or socially, as exemplified in Figure 14.

The recent years have seen a lot more of these “encouragement” and “therapeutic” messages, often written in Chinese, particularly Cantonese. Some are cited from scriptures, like 煩惱即菩提 (Woes and worries are bodhi), which is suggestive of Buddhist thought. Others appear to be laments of sorts like 傷心欲絕 (Sadness that begs for termination). Some are longer messages about love, e.g. 我終於搵到妳,但你終於都係搵咗佢 (I finally found you, but you finally chose him). Lewd messages are rare.

Respect for beauty

As far as I have been able to determine, Hong Kong graffiti in the last few decades have been largely disciplined, and have embellished many dilapidated walls, enlivening otherwise boring surfaces. They have high aesthetic value and deserve appreciation.

Most writers understand that their works are ephemeral, to be painted over by the authorities, vandalised, and eroded. All writers interviewed were clearly respectful of beauty. I have observed this myself.

There was a dull grey wall just outside of Shek Kip Mei MTR station. For about two years, graffiti kept appearing on it despite the dogged repainting efforts by the authorities. A few months ago, the town council made a colourful mural of the Shek Kip Mei and Sham Shui Po neighbourhood. No graffiti has appeared on that wall ever since.

Personally, I feel the Hong Kong authorities have not been very heavy-handed. I hope they continue with their magnanimity. The balanced tolerance promises positive effects...

Although Hong Kong street art has its Banksy moments, the Hong Kong government did pledge efforts to boost creativity and appreciation, including recovery of works by the late Tsang Tsou-choi, King of Kowloon. Notably, the City University of Hong Kong recently commissioned famed Hong Kong graffiti writer “Uncle” to cover quite a few of their walls.

Balanced tolerance

Personally, I feel the Hong Kong authorities have not been very heavy-handed. I hope they continue with their magnanimity. The balanced tolerance promises positive effects, healing a city whose decline many barely dare lament only privately under bated breaths. This must not be underestimated even if it is hard to quantify.

Here is a proposal: invite the world’s graffiti writers to a week-long festival at a conspicuous canal or a few trains to showcase their tags in ways that celebrate their respective home cities/towns. There are many superb writers across China. Indonesia is also very advanced in graffiti culture. Even Singapore has a team of some international acclaim — the “Rscls” led by Antz.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to the many graffiti writers interviewed, all of whom must remain anonymous, and to my assistant Grey who connected me to these writers. The project is funded by the Hong Kong Baptist University (grant BSRF/21-22/01) with support from Molotow, Hong Kong. I am grateful to Ng Kum Hoon and Jason S Polley for saving me the embarrassment of many writing errors. The remaining faults are mine.