Lang Lang on the future of classical music

If you think that classical music is gradually becoming obsolete, world-renowned pianist Lang Lang begs to differ. In an interview with Lianhe Zaobao associate editor and Fukan editor Woo Mun Ngan as part of Lianhe Zaobao’s Future 365 interview series, he says that classical music is as relevant and important as ever, and that social media and AI technology have made the genre accessible to a wider audience.

Amid sub-zero winter temperatures, a group of excited young pianists eagerly awaited the arrival of pianist Lang Lang at the backstage area of the Tianjin Grand Theatre’s opera hall, oblivious to the freezing cold. When Lang Lang showed up, the young pianists cheered loudly, giving him a warm welcome.

Lang Lang had a solo recital scheduled at the venue that evening. Toward the end of the performance, the organisers arranged for 64 young pianists to join him in playing the Radetzky March and My People, My Country. Time was tight on the rehearsal earlier that afternoon and the results were far from perfect — the children’s skill levels varied, their timing was off, and the pianos shook the heavens as they were hammered like percussion instruments. Yet the young pianists’ faces were aglow with hopes and dreams.

Perhaps the next Lang Lang might emerge from among them. At the very least, early exposure and immersion may make them music lovers. Children are our future, especially in classical music — often seen as the pinnacle of high culture.

Is classical music still relevant today?

Classical music is not a luxury; as part of humanity’s spiritual heritage, it offers a unique life experience that can bring joy or move people to tears. However, with the decline of the recording industry and an ageing audience, and in an era where the senses are saturated with “fast culture”, classical music, with its rigour and depth, will never be as accessible as pop music. Can it continue to hold universal value? Does it have a future?

In 2023, Swiss philosopher and sinologist Iso Kern asked if young people would still be interested in classical music in 20 years. It was a mindblowing question.

At the time, Lang Lang expressed great optimism, highlighting the enthusiasm and talent for classical music shown by young people in China and Asia. He argued that as long as classical music is performed well and properly, there will be no need to fear a lack of interest among young people. The pianist firmly believed that interest in classical music would not dwindle, nor would the classical music industry decline.

He said this not because he is a pianist, but because he has seen the awe inspired by countless classical concerts in audience members, the passion of numerous classical music enthusiasts, the success of many classical music compositions, and how classical music festivals and events continue to thrive.

Lang Lang: there will always be a place for classical music

One year on, during breaks in his rehearsals and performance in Tianjin, Lang Lang reiterates his confidence in the future of classical music.

“The pandemic was worrying, and music festivals suffered significant losses during that period. But audiences have gradually returned, and people quickly realised the importance of sharing experiences in concert halls. Personally, I believe classical music will never disappear, but we can also do more. After all, classical music isn’t easy to understand, and the new generation of musicians has realised they can’t just focus on their performance alone — they need to spend time bridging the gap with their audience. For example, my good friend Ray Chen has done many bold experiments on social media, which I find fascinating.”

Ray Chen, a renowned Taiwanese-Australian violinist, is also an internet “funnyman” who frequently posts humorous videos on social media to help more people understand and fall in love with classical music. He has over a million followers on Instagram alone, combining artistry with mass appeal.

“In the past, I might have thought that just playing the piano was enough. But I now recognise that I have to master various forms of communication, and put some time and energy into sharing what I enjoy doing to get closer to the audience.” — Lang Lang

Since the advent of social media, classical music seems to have experienced a renaissance, allowing performers to build popularity quickly, step off their performing pedestal, actively break barriers, accelerate the dissemination of music, and find new growth opportunities for classical music.

According to the Sound of the Internet report published by royalty-free soundtrack provider Epidemic Sound, the global use of classical music surged by 90% in 2022 due to its popularity among content creators on YouTube, while its classical music titles saw 200 million plays on TikTok and other streaming media platforms.

This surge in interest has inspired Lang Lang — who currently has more than 16 million Weibo followers — to embrace social media trends. “I’m also creating my own vlogs now. I document every place I perform and edit several concerts together. In the past, I might have thought that just playing the piano was enough. But I now recognise that I have to master various forms of communication, and put some time and energy into sharing what I enjoy doing to get closer to the audience.”

The healing power of music

On 28 December 2024, the day before my interview with Lang Lang, Israeli forces raided the largest hospital in northern Gaza, forcing the evacuation of 15 critically ill patients and 50 caregivers whose lives were at risk.

The situation made me question if there was any meaning in discussing the future of classical music, in the face of war and death.

Composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein once said that he believed even the faintest music amid the flames of war is stronger than any armour. “This will be our reply to violence: to make music more intensely, more beautifully, more devotedly than ever before.”

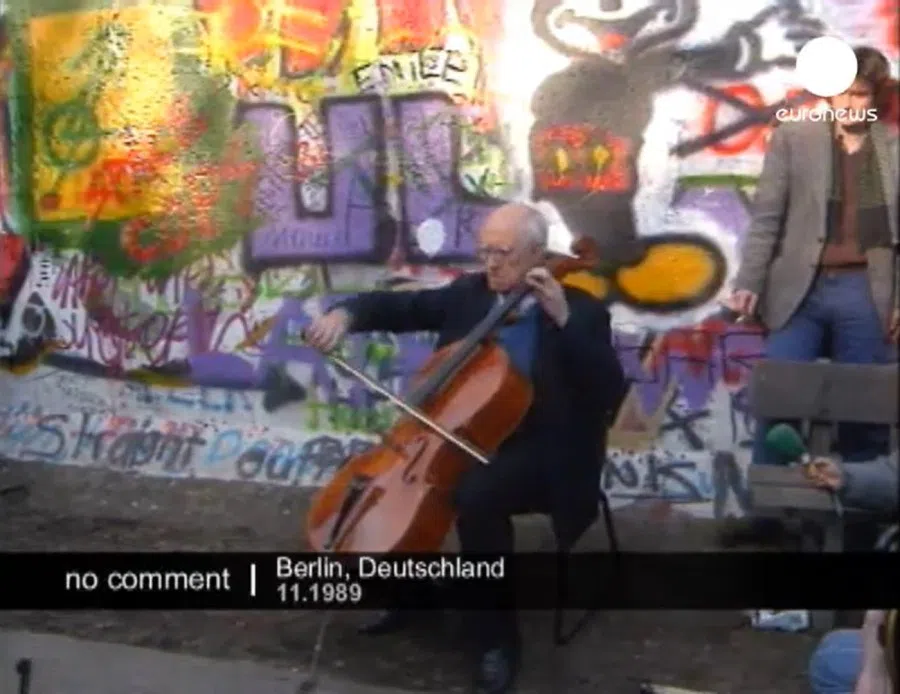

In 2020, following a devastating explosion in Beirut’s port district, cellist Yo-Yo Ma recorded Bach’s Cello Suites to express solidarity with the people of Beirut. Similarly, the image of Mstislav Rostropovich performing the same piece in front of the remnants of the Berlin Wall remains etched in memory — a poignant elegy for the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Iron Curtain.

Classical music has never been an altar in hallowed halls; it has always been a spiritual force responding to societal injustice. Lang Lang said, “The world is indeed at a crossroads. In times of danger, music is needed more than ever to comfort and unite people. I believe that music has a unique power to bring people together, remove prejudices, and resolve cultural conflicts. Many conflicts arise from misunderstandings or differences in interpretation.”

Classical music is a universal language that can transcend barriers and break down divides. “When you hear Ode to Joy, you can feel the heartbeats of people all around the world pulsing in unison. In many difficult moments of my life, music has pulled me back from the edge. The power of music is difficult to express in words.”

A United Nations Messenger of Peace, Lang Lang has consistently used his platform as a musician to advocate for peace. “Conflicts will always exist, but I believe avoiding war is crucial for humanity.”

Beyond promoting peace, he actively participates in public welfare initiatives with international organisation WildAid, urging people to protect marine life and take action in response to global warming. Musicians, after all, should not simply live in their own bubble.

In 2008, Lang Lang founded the Lang Lang International Music Foundation, which has since helped tens of thousands of children access arts education and fulfil their musical dreams. He hopes that music will be able to touch the soul of every child, just as music once transformed his own life.

Music education: a transformative experience for vulnerable children

Amid the chaos of an uncertain future, music education shines like a guiding light. This brings us to El Sistema, Venezuela’s music education programme that has created miracles. Founded by Venezuelan educator José Antonio Abreu, El Sistema champions the idea that music can transform a child’s life, bring them spiritual enrichment and help them resist material poverty and overcome the harsh realities of life.

Since its establishment in 1975, El Sistema has redirected over 700,000 youths living in slums and at the margins of crime onto a better path by providing them with classical music education. Many have gone on to become renowned musicians — one of its most astounding and celebrated success stories is Gustavo Dudamel, who is currently music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and one of the world’s most sought-after conductors.

The concert for the grand reopening of the restored Notre Dame cathedral in Paris featured Dudamel as conductor and Lang Lang as piano soloist. Lang Lang said, “I’ve learned so much from Dudamel. He comes from Venezuela, where youth crime rates are extremely high. But over the decades, El Sistema has slowly educated children through music, teaching them to play instruments and form symphony orchestras. Today, many musicians from Venezuela are recognised worldwide — Rafael Payare, the music director of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra, is another product of this system. I think it’s really great.”

The Venezuelan National Youth Orchestra, another product of El Sistema, frequently tours worldwide, often conducted by Dudamel. Lang Lang once attended one of their performances in London. “You could feel an incredible energy, the effect was so good — it brought out the goodness and love within people. It was really inspiring.”

Through his own foundations, including the Lang Lang Arts Foundation, Lang Lang has long been making a meaningful impact in music education. He often performs alongside young pianists to inspire their love for the art of piano. To fulfil his commitment to ensuring that all children — regardless of their socioeconomic background — have access to quality education, Lang Lang initiated the Keys of Joy programme. Over the decades, this initiative has brought music to many underprivileged children through the donation of pianos and the establishment of music classrooms.

“It was definitely not Vienna. But in the compound where I lived, everyone was practising Mozart or playing The Shepherd’s Flute. Before the age of five, I didn’t realise some people in the world didn’t play the piano.” — Lang Lang

The key to becoming a successful musician? A genuine passion for music

It is well known that Lang Lang’s upbringing was strict, and his education rigorous. However, the main goal of Keys of Joy is that “children are happy when practising piano and that the desire to play comes from within, rather than being forced to do so”.

Lang Lang’s situation was unique — his competitive spirit and unyielding character were well-suited to his father’s “tiger dad” parenting style. A critical factor in his success was his genuine and heartfelt passion for music, which remains the most essential foundation for learning it. As a result, the “Lang Lang model” of success cannot be easily replicated. As a father himself, Lang Lang knows he will not raise his son the same way.

“I think there needs to be some flexibility in music education. You can’t treat all children as if they’re machines to be trained mechanically. Teachers shouldn’t be overly strict, especially when teaching children. Overly strict teaching can easily strip away a child’s natural musicality, turning them into a machine. So, it’s important to strike the right balance and leave room for children to express themselves. Don’t say this or that is wrong, or that things have to be done a certain way. Music isn’t like that. Rules are for adults, not kids.”

Lang Lang believes that nothing beats having a good teacher and environment. At the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, he met his mentor Gary Graffman. Graffman noticed that Lang Lang was too focused on results, and gently guided him toward firmly putting art first. In two years under Graffman, Lang Lang learned 40 concertos, building an ample repertoire to become a professional pianist.

Born in the industrial city of Shenyang in northeastern China, Lang Lang said, “It was definitely not Vienna. But in the compound where I lived, everyone was practising Mozart or playing The Shepherd’s Flute. Before the age of five, I didn’t realise some people in the world didn’t play the piano. Even a small environment can have such an immense influence.”

Music in the age of AI

Classical music continues to spread and exert its influence and function today, even though it has been over 1,500 years since classical music first emerged during the Middle Ages. But in the 21st century, where artificial intelligence is replacing many human functions, the critical question for classical music may no longer be whether young people will remain interested in it, but rather: will classical music lose out to AI?

Standing at the intersection of science and art, Lang Lang has already witnessed the prowess of robots in 2017, when an Italian-designed robot named TEO (TeoTronico) performed Chopin’s Fantaisie Impromptu flawlessly in a man-vs-machine showdown. When playing Flight of the Bumblebee in a speed challenge, the human lost to the robot by just two seconds.

While robots are undeniably fast and precise, Lang Lang had no hesitation in distinguishing the robot from the human performer based on a single wrong note and the dynamics of the piece. “The robot was too perfect, and that actually took away from the live experience because you know it can’t make mistakes. I think people still prefer watching humans play the piano. Robots can only replicate — they have no warmth, no emotion.”

“But can AI reach the level of Mozart, Chopin or Beethoven? I haven’t seen that yet. It’s really just a tool. You feed it into a vast dataset, and it can learn, mimic and replicate, but to create something entirely new on its own — it can’t do that.” — Lang Lang

Lang Lang believes AI has proven effective in music education. As a practice companion, it has clear advantages, as it can repeat endlessly without ever tiring. Steinway’s innovative Spirio system exemplifies this, capturing every detail of a live performance while offering recording, editing and playback capabilities. With just an iPad and a few taps, users can recreate the effect of a live performance, essentially bringing a piano master into their home — an astonishing leap in technology.

“But can AI reach the level of Mozart, Chopin or Beethoven? I haven’t seen that yet. It’s really just a tool. You feed it into a vast dataset, and it can learn, mimic and replicate, but to create something entirely new on its own — it can’t do that.”

Music remains a profoundly human art, a medium of deep personal expression. Every artist’s style and emotional depth evolve over time. No matter how advanced AI becomes, it will ultimately always be a reflection of logical thinking; AI does not feel, nor can it convey genuine emotion.

We should be glad that the future of classical music does not hinge on competing with machines. Instead, music can transcend boundaries, express emotions, bridge differences and inspire strength, allowing us to come to terms with — and fight — the pain and suffering that inevitably accompany the human experience.

Lang Lang’s recommended booklist:

Parallels and Paradoxes: Explorations in Music and Society by Daniel Barenboim, Edward W. Said, Ara Guzelimian

This book documents the dialogue between two prominent contemporary cultural figures — musician Daniel Barenboim and literary theorist and critic Edward Said. The two were close friends, sharing similar experiences of displacement and originating from complex and interwoven cultural backgrounds. Over the course of six conversations spanning five years (1995–2000), they engaged in profound intellectual exchanges and sharp debates on music, culture and politics.

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

Hamlet is William Shakespeare’s most renowned play, embodying profound tragic significance. Through the character of Hamlet, the work reflects the conflict between humanist ideals and feudal realities. Themes such as power, corruption and human frailty are also explored in depth throughout the play.