The 'late style' of 102-year-old artist Lim Tze Peng

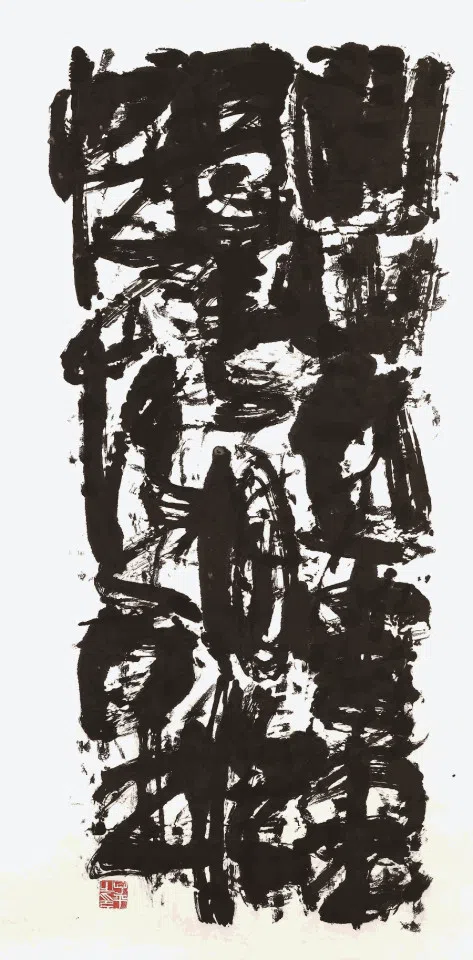

Artist Lim Tze Peng, who turned 102 this year, was born and bred in Singapore. From having a firm grasp of traditional Chinese painting techniques, he continually experimented with different methods, adjusting his style and finding a new path. Writer Teo Han Wue was there to witness the artist's pivotal change in style some 15 years ago, when the artist was in his 80s. This was when Lim experimented with using bold, cursive-style calligraphic brushstrokes to create near-abstract and completely abstract paintings, with trees as the main subject matter - a style which came to be known as hutuzi (糊涂字, "muddled writing"). Lim's "late style" continues to evolve, even until today.

(Photos courtesy of Teo Han Wue.)

If I say centenarian Lim Tze Peng is the brightest star in the Singapore art scene today, I am sure few would disagree or even find it in the least surprising.

The reason is quite simple. At 102, he is as sprightly as a man half his age. Though a little hard of hearing, he still speaks with a booming voice and articulates his thoughts lucidly.

More than that, he diligently paints and does calligraphy every day, producing a prolific body of work and constantly experimenting with new ideas and innovative methods in search of a breakthrough in the art of ink painting.

For some time now, he has been maintaining a high visibility by releasing a large number of works which are keenly sought after by various galleries. At the moment, an exhibition held at the Lim Tze Peng Gallery in Ubi in commemoration of his birthday has been discussed enthusiastically by his followers.

Even more significantly, a selection of his latest works was exhibited in London at the renowned Saatchi Gallery in October as part of the 10th annual StART Art Fair there.

A living legend

There is yet more to look forward to. Come next year, Lim will be featured in a special exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore as probably the most senior living artist ever to hold a solo show at the gallery.

According to Ng Siang Ping, senior art correspondent of Lianhe Zaobao who flew to London to cover the exhibition, Lim amazed many Western viewers with his highly energetic and contemporary ink expressions; they did not believe that such pieces could have been done by an artist of his age. "In fact, Lim Tze Peng's show was undoubtedly the highlight of the entire art fair," said Ng.

I cannot think of any artist in Singapore who can come even close to this glowing record. Not least in terms of his energy level at such a late age or his tenacity and creative spirit. He is truly a living legend of our time!

I am inclined to regard Lim's late maturity more as a new phase of difficulty, tension and unresolved contradiction rather than reconciliation and harmony.

Blossoming at a later age

Much has been written about him and his achievements on various platforms such as social media and printed material like books and exhibition catalogues. I would therefore like to focus instead only on how the artist's "late style" began to emerge.

Writer Edward Said in his book On Late Style asks, "Does one grow wiser with age, and are there unique qualities of perception and form that artists acquire as a result of age in the late phase of their career?" Said thinks some late works possess "a special maturity, a new spirit of reconciliation and serenity often expressed in terms of a miraculous transfiguration of common reality". And yet he questions the idea of late serenity by contemplating what if artistic lateness was not viewed in terms of harmony and resolution but "intransigence, difficulty, and unresolved contradiction".

I am inclined to regard Lim's late maturity more as a new phase of difficulty, tension and unresolved contradiction rather than reconciliation and harmony. It is quite clear that Lim has been challenging himself with new ideas, methods, experiments and explorations and creating works that are increasingly more difficult and abstract. Though he occasionally reprises old themes and subjects such as Singapore River and familiar old street scenes, they are not exactly about reconciliation or resolution.

The fascinating journey of his late style began with his exhibition titled "Inroads: Lim Tze Peng's New Ink Work" as a turning point in his painter's practice. The solo show in 2008 at Art Retreat, a private museum incorporating Wu Guanzhong Gallery, was a major milestone. For more than a decade since then, I have been following Lim's career closely and have gained some understanding of his art and thought process.

As the change was highly dramatic and appeared in stark contrast to his earlier work, some people described it as laonian bianfa (老年变法, "reform in old age").

Turning point when the artist was in his 80s

Planning his exhibition at the time as director of Art Retreat, I selected some of the best of his new works produced recently in his 80s. The works reflected a completely new style distinctly different from his earlier paintings. As the change was highly dramatic and appeared in stark contrast to his earlier work, some people described it as laonian bianfa (老年变法, "reform in old age").

Lim himself was nervous, fearing followers of his art being used to his previous style might find the change too abrupt and thus hard to accept. As things turned out, his fears were completely unwarranted.

First of all, viewers of Inroads were impressed with his new experiments affirming the merits of his use of bold, cursive-style calligraphic brushstrokes in creating medium to large format near-abstract and completely abstract paintings, with trees as the main subject matter. His new calligraphy was now rich in gestures of brushstrokes soaked in ink looking like doodles which are actually wildly cursive writing that has gone illegible almost completely beyond recognition. Many call it hutuzi (糊涂字, "muddled writing").

At this critical juncture, Lim was pleased with the encouraging response to his change. What delighted him even more was the subsequent development in which the exhibition came to be a significant turning point in his artistic journey in the later years. In addition to the warm reception he was enjoying from home, the exhibition also won commendation from two distinguished scholars of international standing from abroad.

On the road to exhibiting in China

When he was passing through Singapore, Wu Hung of Chicago University, a renowned art history professor and curator of contemporary art, came to see the exhibition with Kwok Kian Chow, then director of the National Gallery of Singapore. After viewing the works, Wu told Lim personally that the latter's experiments in ink were working and going in the right direction, especially his hutuzi.

Professor Wu was formerly a researcher at the Palace Museum in Beijing before he went to study at Harvard and graduated with a doctorate in both art history and anthropology. He once taught at Harvard and has published many important books.

Another visitor, Professor Fan Di'an, then director of the National Art Museum of China, made an even greater difference. Prof Fan saw Inroads accompanied by Kwok and was instantly impressed and asked for a copy of the catalogue. He called on Lim at the latter's home the next day to talk to him and to see more of his work in his studio. There and then, he extended an invitation to the artist to exhibit in Beijing.

That was how Lim's exhibition began its journey in China where it went on at the Liu Haisu Art Museum in Shanghai after its run in Beijing.

Always reaching for the next peak

Never one to sit on his laurels, Lim has continued to work diligently since his success in China more than a decade ago The new work we keep seeing coming from him to this day never ceases to surprise us as it is always the result of his explorations and experiments to break new grounds for his ink work.

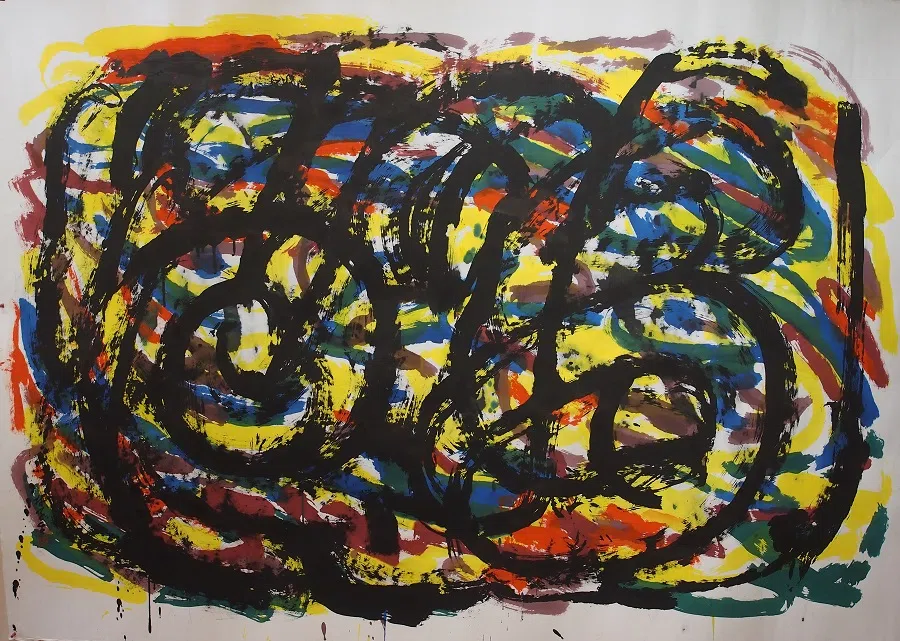

While he has often revisited and reworked some memories of his familiar subjects, he has also tried out new approaches and materials such as ink and paper resulting in a completely new look in his painting.

Once I visited him in his studio where I noticed books on Joan Miro among his reading materials. He told me how he was fascinated by the Spanish surrealist's innovative use of lines and colours, which I understood to be what inspired Lim's palette and brushwork in his more recent works painted with Japanese colour ink generously supplied by his collector friend, Ong Teng Huat.

I recall how on another occasion we talked about calligraphy, which he often stresses as the foundation of his painting. At that time, I gave him a book on the contemporary Japanese calligrapher Inoue Yuichi whom he admitted to not being familiar with before. Browsing through the book, he was pleasantly surprised by how unknowingly, and in his own way, he had been experimenting with calligraphy in a rather similar way that Yuichi had.

While there is still light the view up there must be magnificent with the sky illuminated by the sun's golden rays.

In 2016, I wrote for the exhibition of Lim Tze Peng's late works at the Cultural Centre of the National University of Singapore and discussed the development of his late style. I described Lim's later creative phase as an "evening climb", borrowing from the title of Singapore theatre artist Kuo Pao Kun's later play about a group of old people climbing a hill in search of a mysterious big bird.

In conclusion, I wish to quote from my essay for that exhibition titled "View on the Hill: Lim Tze Peng's Evening Climb":

"The day is not done and this fearless elderly climber has reached heights that would have defeated many much younger ones attempting the same ascent. While there is still light the view up there must be magnificent with the sky illuminated by the sun's golden rays. No matter if one finds what one is looking for, the climb itself must have been rewarding enough."