[Photos] Xie Xin: The superstar bringing Chinese contemporary dance to the world

Shanghai-based writer Kyle Muntz speaks with Xie Xin, a star choreographer in China’s contemporary dance world. He learns about dancers’ commitment to their passion and a dance form that could be called the live equivalent of abstract painting.

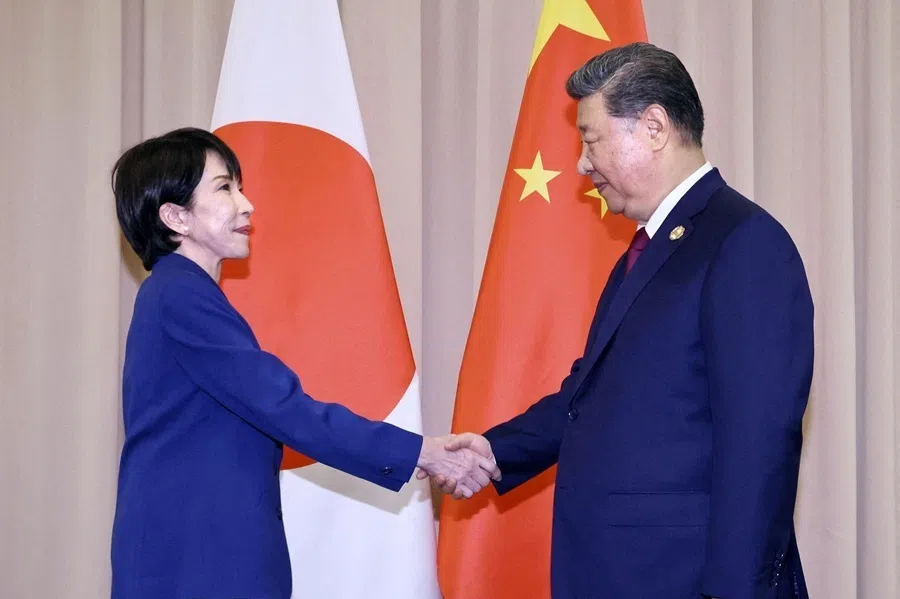

(Photos provided by Xie Xin’s press team)

With a thunderous burst of pounding drums, the Xiexin Dance Theatre’s “In Satie: The Rite of Spring” made its premiere at the Shanghai International Dance Center from 21-23 February — the same historical venue where, over the last half century, hundreds of the country’s largest performances have been featured for the first time.

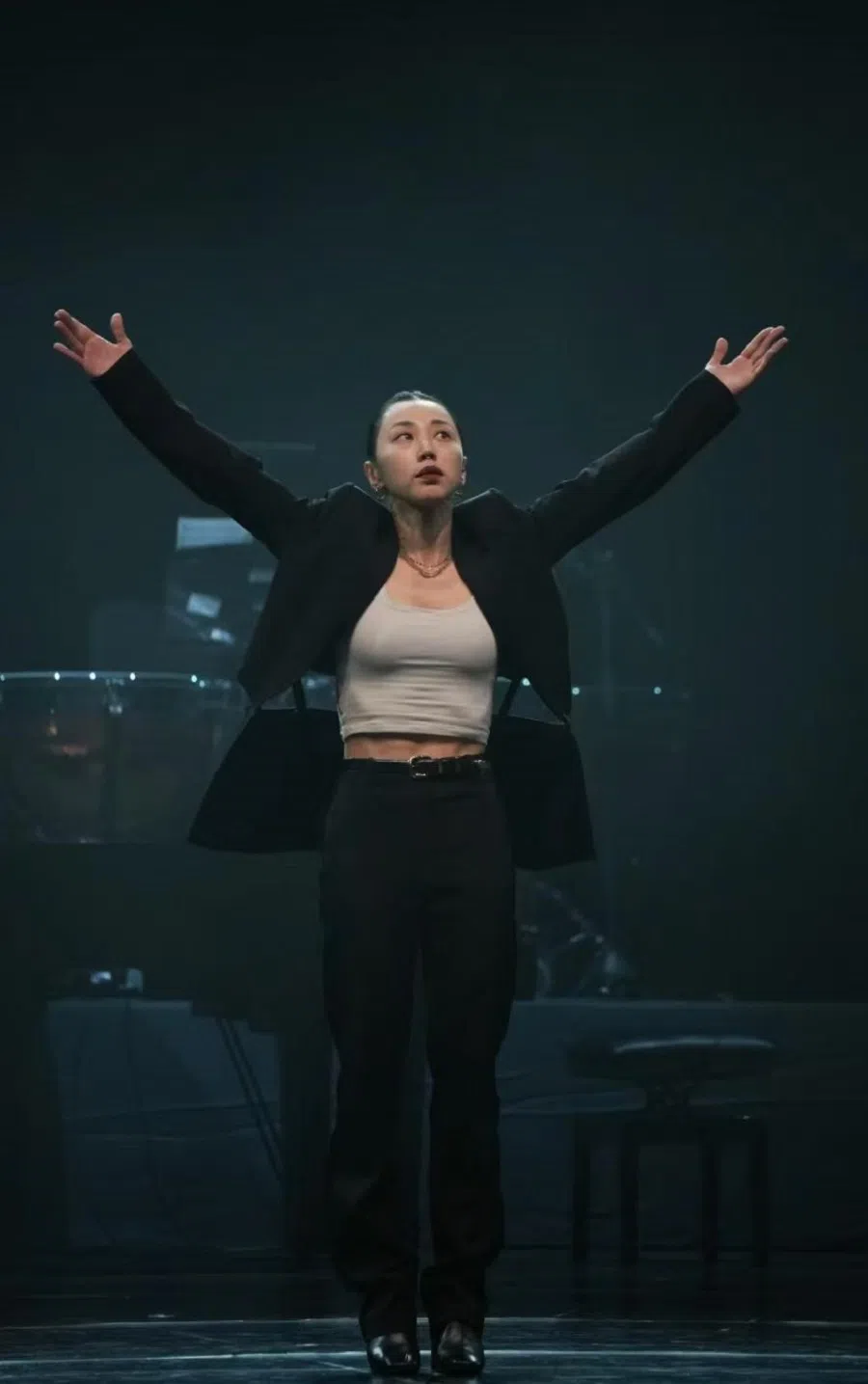

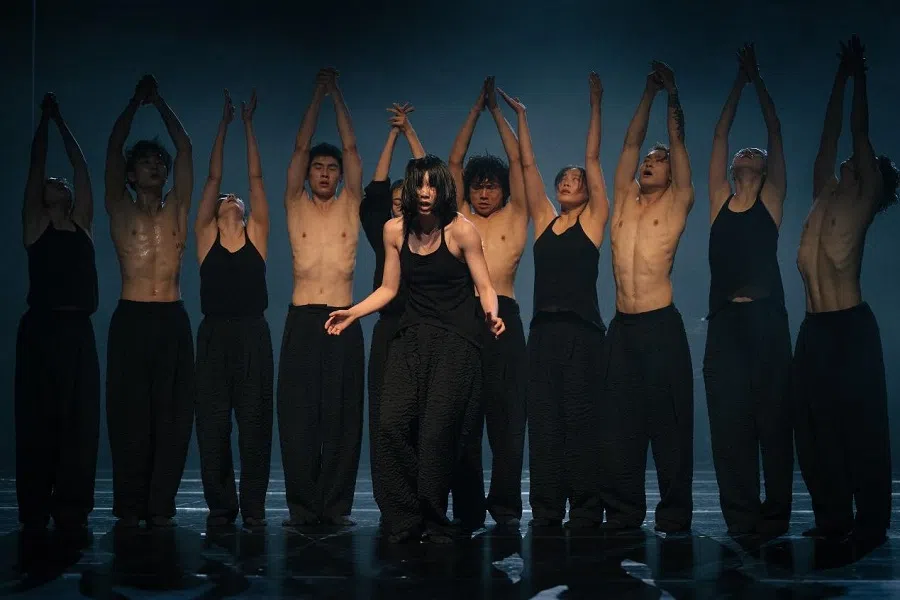

In the first half, dancers glide like silent wraiths to the gentle piano melodies of Erik Satie’s Gymnopedies. Later, this escalates to a violent, crashing assault of writhing limbs and contorting bodies set to Igor Stravinski’s Rites of Spring — “like magma breaking through the forbidden copper percussion of double pianos and pumping out the blood of ancient rituals,” writes Shanghai arts magazine iWeekly. But despite that, the loudest moment of the night occurs when Xie Xin, founder and artistic director of Xiexin Dance Theatre, steps onstage herself, raising both arms to bow to the crowd.

“There is no contemporary Chinese dance without Xie Xin,” Shenyuan Hu, another prominent dancer and composer once said. Tonight, the dancer, choreographer and owner of one of China’s most prominent dance groups needs no introduction; the crowd already recognise her from TV programmes such as Ride the Wind and Hello Star Six, not to mention countless viral videos. And soon, when this show begins its world tour, more people may know her overseas as well.

... Xie Xin is one of China’s foremost practitioners of contemporary dance, so called because — unlike ballet, with which it is often confused — its history traces back only to the 20th century.

Practising an ‘incomprehensible’ artform

But the dance featured onstage is very different from the hip hop and popular dance so common on TikTok (or, in China, its mother-app Douyin). Rather, Xie Xin is one of China’s foremost practitioners of contemporary dance, so called because — unlike ballet, with which it is often confused — its history traces back only to the 20th century. This kind of dance is “incomprehensible, not pretty”, writes a RedNote user from Guangdong, made up of an often baffling series of contorted body positions, frequently challenging users not just with the strangeness of the choreography but the ambiguity of its ambitious hour-long, theatrical performances, which stretch the possibilities of the human body while simultaneously functioning as the live equivalent of abstract painting.

But for Xie Xin, and China more broadly, contemporary dance truly is contemporary — a history brief enough that, though her company has only existed for ten years, it overlaps significantly with her own life and career. “The development of contemporary dance in China up to now is actually quite different from that in foreign countries because it has only existed for 40 years,” she says, in an exclusive interview with ThinkChina. “When we perform in Europe, we can see the dance troupes in China are already top quality. But I think in China, in terms of the diversity of works, the diversity of aesthetics, and the richness of creativity, there will still be many breakthroughs.”

“Dancers or choreographers in Europe have a more direct style, like they’re on the attack, but Chinese culture is different, it has a certain openness.” — Xie Xin, Founder and Artistic Director, Xiexin Dance Theatre

‘A certain openness’

Xie Xin is acutely aware that most overseas audience members have likely never seen a dance performance from China, but she’s also confident that she has something unique to offer. “Dancers or choreographers in Europe have a more direct style, like they’re on the attack, but Chinese culture is different, it has a certain openness,” she says, reflecting on her time working and studying in places such as New York, Berlin, and elsewhere. “We don’t deliberately try to show something, but rather to see whether there are some differences in the nature of the body’s performance, the expression of emotions, or everyone’s subjective feelings.”

Frequently, when Xie Xin discusses her work, she transitions to poetic language that evokes a vague sense of spirituality as well as the notion of “qi”, a kind of effervescent, invisible energy in the body which also informs the traditional practice of Taichi. “For me, there’s a deep curve: you receive the energy from other people, then you change it and send it out again,” she says. “If there is no air, no breath, then there is no movement. So it’s a circle of feeling. You always feel the energy as you move: it changes your body and takes you where you want to go.”

At one point, the company had only 10,000 RMB on the books — but despite this, she was determined to push on without firing any of the company’s over 20 employees...

Despite this, Xie Xin’s adaption of Stravisky’s Rites of Spring is a jarring, physically demanding performance, even ugly — a fitting companion to music that, upon release, was sometimes dismissed as too “barbaric” for audiences, with its depiction of a sacrifice ritual among vanished Russian tribes.

But for Xie Xin, the violence of the music echoes the more tangible tragedy of the surprise fire that burned down her dance studio in 2023, sending the company hurtling towards bankruptcy and making the preparation for this performance one of the most difficult of her life. At one point, the company had only 10,000 RMB on the books — but despite this, she was determined to push on without firing any of the company’s over 20 employees, though the struggle sometimes felt hopeless.

Gruelling work

“I feel that through this process, I discovered that there is a kind of vitality in the human body and life,” she says. “It grows out of a wound, it blooms from pain.

Between takes, dancers regularly stumble, heaving, from the floor; vomiting is a regular occurrence, both from the nausea of rapid motion and the simple exertion of the choreography.

In Xie Xin’s version of the Rites of Spring, this pain isn’t simply metaphorical. Seen from a seat in the theatre, the dance looks elegant and clean to the hundreds of audience members in the theatre — but up close, preparing for the show in their studio at the edge of Shanghai is gruelling, brutal work. The dancers wear loose-fitting, long-sleeved clothes to avoid the floor becoming slick with sweat. Between takes, dancers regularly stumble, heaving, from the floor; vomiting is a regular occurrence, both from the nausea of rapid motion and the simple exertion of the choreography.

“In our usual rehearsals, the dancers in our troupe are relatively more tired than those in other troupes, because our works are very intense,” says Xie Xin. Five days a week, rehearsals begin at 10am, with only a few brief, 15-minute breaks until practice ends at 6:30. Seen from up close, the dancers look and sound more like extreme sports athletes — an impression emphasised by the constant expressions of visible pain which are an important aspect of Xie Xin’s vision for this adaptation of Rites of Spring.

In comparison, Xie Xin’s appearances on TV — such as Ride the Wind, where she emerged as the champion — are a much shorter, simpler challenge. “When participating in a TV programme the length of a work is usually no more than two minutes, so you have to be quick, accurate, and ruthless. TV directors want to set the rhythm and keep the audience in suspense. It’s all very fast and accurate — different from the stage, where you slowly develop ideas and are presenting audiences with a much larger picture.”

Part of a larger picture

Despite her success on TV, Xie Xin prefers the more open, ambitious space of the stage. She hears the music, and inside, a vision unfolds, emerging from a combination of intuition and inspiration — though it will be four to six weeks of practice before she actually sees her dancers performing it in reality. “You can’t just control individual movement, because each of your actions must be part of a logical process in the larger work. It makes a larger musical picture, sudden and cold but complex. At the same time, you need movement, you need musicality, you need the logic of the work itself.”

After years of preparation, many sacrifices have been spent to get this performance onstage. Xie Xin recalls days spent crying, wondering at the future of the company; at times, the pain was so intense she could not even clean her apartment. But the equipment, props and costumes burned in the fire have now been replaced. Despite spending over 2 million RMB to rebuild, Xie Xin and her husband Liu He — “the pillar of the company” and “the most important person who makes all this possible” are now looking eagerly towards the future.

“... even if they may not have a lot of income like the big businesses in China, dance groups are making money and have options available to them. It’s a great time for independent artists to make progress.” — Xie

A promising era for contemporary dance

“In fact, I’m very grateful to be dancing in this era,” Xie Xin says. “These days, the theatres in every city and every country have very good audiences — the whole environment and cultural atmosphere supports them with stable investments. So even if they may not have a lot of income like the big businesses in China, dance groups are making money and have options available to them. It’s a great time for independent artists to make progress.”

On stage, Xie Xin bows for nearly five minutes, pushing her dancers ahead while the applause refuses to fade — but even when the curtain closes, the show is far from over, as it will soon be seen by audiences around the world.

“I often tell my dancers — this isn’t just for us,” Xie Xin says. “As a Chinese choreographer, I always had a strong sense of responsibility towards Chinese modern dance when I go abroad. In this era, it seems that you cannot retreat, you can only move forward. As the country keeps developing, I believe it will naturally reach the next destination. Maybe not in my lifetime — but a new golden age is definitely coming.”