Venice Biennale 2024: Troubled worlds on art’s stage

Keong Ruoh Ling decodes the 60th Venice Biennale 2024, seeing it as a framework of understanding the world. The stories of those on the margins — the migrants, the outsider artists, the global south — come together in a patchwork of artworks. In the theatre of the geopolitics of art that is the Venice Biennale, one sees the different acts playing out.

Walking into the Central Pavilion of the 60th Venice Biennale, the Giardini, one is immediately brought face to face with the brightly coloured facade of the entrance.

Covering the walls in every quarter including the columns and architrave are the flamboyant imageries of patterns, animals, human beings and vegetations. This artwork is created by MAHKU (Huni Kuin Artists Movement), an indigenous collective founded in 2013, based between Jordão city and Chico Curumim village in the Kaxinawá (Huni Kuin) indigenous territory along the Jordão River.

Between humans and all living things

Beginning in the late 2000s, this collective has organised workshops in universities to record the Huni Kuin chants, myths and practices in drawings. In the large mural created for the facade of the Central Pavilion, MAHKU has painted the story of kapewë pukeni (the alligator bridge).

The myth describes the passage between the Asian and North American continents through the Bering Strait. In the tale, humans struck a deal with a chief alligator who agreed to carry the humans across in exchange for food. However, during the journey, some of the animals got agitated and hesitant, leading the humans to kill a smaller alligator and thus breaking their pact with the chief alligator.

This tale addresses both migration and the relationship between humans and animals, and alludes to the world’s emergence and species division — central themes for the Huni Kuin people and the biennale.

Adriano Pedrosa, the curator of the 60th Venice Biennale has named the present edition Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, a name taken from a series of work by the Italian-British art collective Claire Fontaine, who has since 2004 created neon signs in different colours that render in an ever-growing number of languages — some living, some indigenous, some archaic and some defunct — of the words “Foreigners Everywhere”.

The phrase is in turn adapted from another Italian collective who fought racism and xenophobia in Italy in the early 2000s. Thus the phrase comes from a very specific context in Italy, the host country of the biennale with which the curator sees its relevance to the world at large.

Adriano Pedrosa would likely be remembered for the inclusion of many “outsider artists”, primarily from the global south and many of whom are first-time participants.

Bringing the outsiders in

“Foreignness” is at the heart of the 2024 Venice biennale and in Pedrosa’s own words, explained in the official website of the biennale, he wants to place artists who are “immigrants, expatriates, diasporic, émigrés, exiled or refugees” in the limelight.

Expanding on the concept of strange, he states further: “… thus the Exhibition unfolds and focuses on the production of other related subjects: the queer artist, who has moved within different sexualities and genders, often being persecuted or outlawed; the outsider artist, who is located at the margins of the art world, much like the self-taught artist, the folk artist and the artista popular; the indigenous artist, frequently treated as a foreigner in his or her own land.”

In contrast to the more open-ended trajectories of previous editions, Pedrosa aimed for viewers to navigate the biennale with a curatorial framework that provides a perspective but not a specific context and specification. Human history, as this biennale suggests, is non-linear, multi-fold, nuanced, layered, disjointed, complex and messy.

If Cecilia Alemani, the curator of the 2022 Venice Biennale would be remembered for devoting the show mainly to women artists, Adriano Pedrosa would likely be remembered for the inclusion of many “outsider artists”, primarily from the global south and many of whom are first-time participants.

Consequently, there are numerous first encounters with unfamiliar names even for the art aficionados, professionals or not, inside the circle or outside, curiously levelling a field that is infamously inclusive and elitist.

The first-timers are not limited to the living artists. Pedrosa also included a huge number of artists who have passed away, and by doing so, he risked undermining a biennale with an original intention of showcasing the contemporaries of the time. Every writing and review of the biennale has not let this slip and the verdict is out.

Jackson Arn, writing for The New Yorker, titled his piece “The Dead Rise at the Venice Biennale”, observing that the dead is actually another category of foreign land. He surmised that “stifled by a weird and desperate present, the show finds some life in the treasure of the past”. And the treasures of the past also tell another sort of journey that is the arrival of Western Modernism in the global south and how it was embraced by the natives.

It is in these rooms that one would find many deceased artists, the relics of the past that underlined the adoption of Western Modernism by the global south.

Stories on the boundaries of the global south

Indeed, alongside the mythical tale of MAHKU that is about crossings, arrivals and departures etched in mind, one comes to an encounter with a smeary, bloody trace of an anonymous Venezuelan migrant who was killed as he crossed into Colombia, in Tela Venezuelana (2019), a straightforward but poignant work by Teresa Margolles who is based in Mexico city. Going by a work motto of “looking at the dead you see society”, she produces works that communicate her observations from the morgue.

Also in the Central Pavilion is the work of first-time participant and a recipient of the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement for Venice Biennale 2024, Turkish artist Nil Yalter, who showcases a new reconfiguration of her previous work, Exile is a Hard Job (1977-2024) discusses lives and experiences of economic immigrants across generations alongside her iconic Topak Ev (1973), literally translated as the round house, a tent that is modelled after the dwellings of the nomadic communities of central Anatolia.

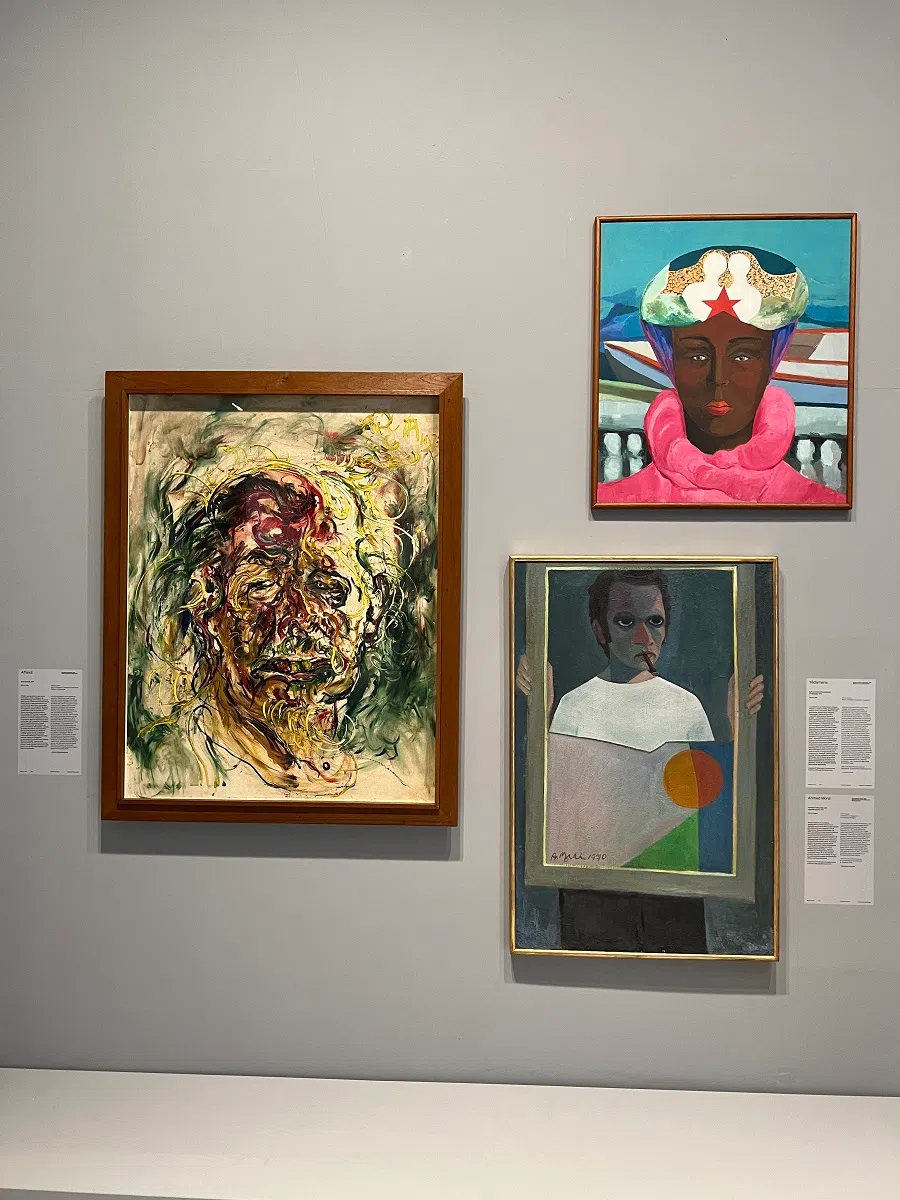

Further into the Central Pavilion are three rooms that are dedicated to works of “Portraits, Abstractions” and the third one is reserved for artists who represent a global Italian diaspora in the 20th century. It is in these rooms that one would find many deceased artists, the relics of the past that underlined the adoption of Western Modernism by the global south.

Henceforth, one encounters the self-portrait of Indonesian modernist Affandi, with its smearing and smudges of paint in full glory; comes face to face with the steady gaze of Georgette Chen, herself an émigré artist from Shanghai who settled in Singapore in the second half of the 20th century; bumps into the classic salon-styled self-portrait of Filipina Anita Magsaysay-Ho; and finally running into the seemingly whimsical Untitled (Mujer Caballo) by Wifredo Lam, who was Chinese by descent but unapologetically Cuban by breeding.

Intercepting the thematic rooms are the various groupings of art that showcase the indigenous, the queer and the subversive ones. Strange and foreign in their respective contexts, they tell a tale of struggle and coming to their own terms respectively.

There are the works of Abel Rodríguez, painter and plant expert who is a Nonuya, an ethnic group that is native to the Amazon rainforest of Colombia. Rodríguez’s works usually focus on the taxonomical exploration of different varieties of Amazonian trees, eager to document the flora and fauna of his native land but yearning to convey the belief of his people that nature and people cannot exist without the other.

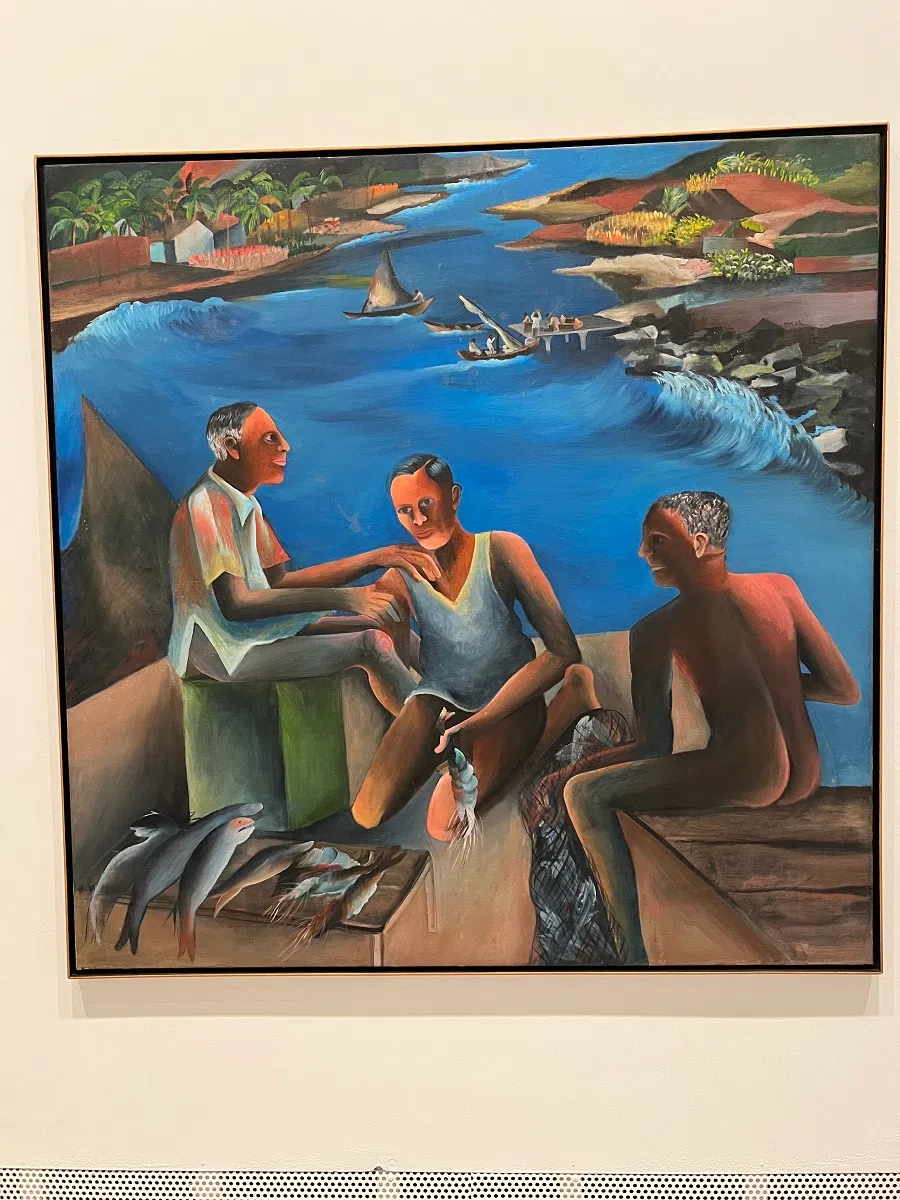

Bhupen Khakhar, born in Bombay in 1934, was among the first artists who painted works that addressed societal taboos surrounding homosexuality in India since the 1980s. Exhibiting his work Fisherman in Goa (1985) alongside Louis Fratino, a young American artist who also paints male bodies in his exploration of the LGBTQ+ community in contemporary society, creates a meaningful dialogue across cultures and generations on the subject.

... foreigners are everywhere and the human colonialisation of outer space is the good old imperialism passing the torch in the name of science and technology and the tale of displacement continues.

Arduous journeys to new lands

Crossing over to the Arsenale exhibition site and Yinka Shonibare, the British-Nigerian artist, awaits at the entrance with his Refugee Astronaut (2015-ongoing). The artwork is a life-sized nomadic astronaut dressed in a waxed fabric with a folksy design and carrying a mesh sack filled with various knick-knacks such as a lamp, a pot and a bag, supposedly equipping the astronaut to navigate ecological and humanitarian crises.

The message is clear: foreigners are everywhere and the human colonialisation of outer space is the good old imperialism passing the torch in the name of science and technology and the tale of displacement continues.

Lydia Ourahmane’s 21 Boulevard Mustapha Benboulaid (entrance) (1901-2021) is literally the door she uprooted and recreated from her rented apartment in Algiers. It features two functioning doors: the first is an original wooden door from 1901, characterised by a distinctive Parisian style that was prevalent during the French occupation of Algiers. The second is a metal door with five locks, added in the 1990s during the Civil War.

Together, these doors reflect the social and political conditions of Algiers throughout the 20th century and provide insight into the psychological tension experienced by the artist. Each additional lock was a personal response to feeling unsafe, illustrating how historical events are deeply felt on an individual level.

Indeed, the response is as personal and mundane as that suggested by Bouchra Khalili’s The Constellation series (2011). A set of eight silkscreen prints that correspond to each of the eight video projects in which the Moroccan French artist interviewed migrants from Africa, the Middle East and South Asia at train stations and got them to describe their journeys across the Mediterranean to Europe — the paths that they eventually took were mapped out from point to point against a deep blue background on silk screen prints.

These journeys are often arduous, complicated and perilous, marked by delays and restarts. Yet, when mapped out as dots, stripped of their specific contexts, they appear as bold voyages with clear starting points and destinations, yet devoid of the intense emotions experienced by the migrants.

‘Everything Everywhere All at Once’

This diverse grouping of artists in unique and respective contexts concocts a dissonant chord that at times seem disconnected and jarring, nothing fits into a box, nothing belongs; some things are dead and others are robustly alive.

What is evident, however, is that it is current, and as suggested by the brilliant title of a review by Adrian Searle in The Guardian, the Venice Biennale 2024 is “Everything Everywhere All at Once”. And this is happening in the Now.

The congregation of the many and various assortments by Pedrosa feels like a snapshot of a busy metro system in any metropolis, the movements of people interwoven with the individual stories that are braided into a larger fabric of societies, communities and states.

This is even more apparent with the presentations at national pavilions, as Adrian Searle quips: “But instead of the global south, a deferred elsewhere, we should probably talk more plainly about the global majority, whose pressing needs and voices cannot be kept on hold.”

If not the violence of a full-fledged war, it would be the violence of a layered past as commemorated by the Australian pavilion.

A troubled world

Violence is mimicked everywhere at the national pavilions. Repeat after Me II (2022, 2024) at the Polish pavilion consists of two films from 2022 and 2024 that recorded the narrations of the war refugees in Ukraine.

These civilian war refugees would speak of the war experience by first describing a firearm, imitating the sound of that particular weapon, and then inviting the audience to repeat after them. A standing microphone is placed in front of the projector almost cajoling the viewers to repeat what they heard from the war refugees.

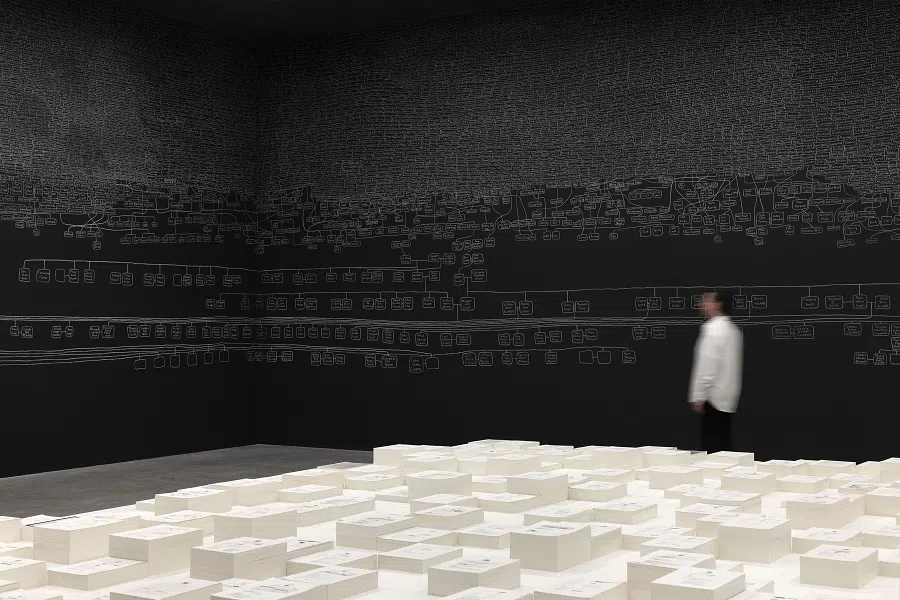

If not the violence of a full-fledged war, it would be the violence of a layered past as commemorated by the Australian pavilion. Archie Moore’s kith and kin (2024) traces his Kamilaroi and Bigambul’s family tree that spans 65,000 years, presenting it as a monumental genealogical chart etched across the black wall.

A reflective pool is installed in the centre of the pavilion, beneath a collection of 500 document stacks detailing colonial inquests into the deaths of indigenous Australians in police custody. The result is elegiac yet painfully affiliated with the current affairs of the world presently.

So between the Giardini and Arsenale — the two main sites of the biennale — and the 87 national pavilions located in between or scattered throughout the city, the exhibition does deliver its title message.

Though not always succinct, it presents a collage of words, thoughts, emotions, events, imaginations and fears that vividly capture the zeitgeist of our present. In the theatre of art’s geopolitics that is the Venice Biennale, one sees the different acts playing out.

... the pavilion of the United States, arguably the only global superpower presently, is perhaps not escapist but certainly evasive of the topic.

US and China: skirting the issues?

The US pavilion by Jeffrey Gibson provides a vibrant reflection on global discourses surrounding indigenous identity. While it aligns with the curatorial brief, it seems somewhat powerless in addressing the current conflicts involving the country.

In contrast, the Israeli pavilion’s curators and artists have taken a stand by closing the pavilion until a ceasefire and hostage release agreement is reached. This response highlights a stark contrast: the pavilion of the United States, arguably the only global superpower presently, is perhaps not escapist but certainly evasive of the topic.

It is, of course, not obligatory to address geopolitical topics at the biennale; for example, China — the enfant terrible of the global stage from a Western perspective — has also chosen to skirt around the issue.

A civilisation as old as time underscores a sense of cultural superiority conveyed by the Chinese pavilion, which is titled culturally correctly as Atlas: Harmony in Diversity. Word play comes to the forefront with a curatorial brief explaining that the ancient Chinese character 集 for “atlas” evokes three birds in a tree and can be used not only as a noun but also as a verb meaning “gather.” Meanwhile “harmony” is genetically embedded in Chinese beliefs that extends to the individual, society and the state.

The theorising ends here, with no mention of the “diversity” aspect of the title in the texts. However, this curatorial agenda aligns with the official cultural and political stance of the People’s Republic of China: China, in its uniqueness, is an invaluable bit of “diversity” to the jigsaw world. In brief, the Chinese way is presented as equally valid, if not more ingenious, than the Western way, highlighting China’s status not only as an ancient civilisation but also as a vibrant one that continues to thrive in the 21st century.

... it suggests that classical China represents paramount artistic excellence and that contemporary China is a direct heir to this legacy of supremacy.

The irony is almost visible: if any of the seven artists picked by the curators to present in the pavilion come from one of China’s 55 ethnic minority groups, they remained unidentified, which stands in sharp contrast with the biennale’s incessant celebration of ethnicity and a heterogeneous world.

Also in the pavilion is an expansive array of vitrines containing pictures of 100 classic paintings currently held abroad, referencing the word 集 in the title: this installation implicitly suggests that the treasures should never have left China and perhaps should be repatriated presently. The intended message is somewhat unclear, but the proud undertone is evident: it suggests that classical China represents paramount artistic excellence and that contemporary China is a direct heir to this legacy of supremacy.

If Pedrosa aspires to challenge the canonical categories of contemporary art and art history by charting out the principle of inclusiveness, the responses of the national pavilions to this idea of inclusion, strangeness, and diversity are indeed multifaceted and revealing of the discourses and realities of our world. In this regard, Foreigners Everywhere unpacks many issues while showcasing more knots along the way.