Yokohama Triennale, Lu Xun’s ‘Wild Grass’ and our lives

Strolling through the 8th Yokohama Triennale held mainly at the Yokohama Museum of Art, former director of the Singapore Art Museum Kwok Kian Chow reflects on the historical woodcut connections between Japan and China and in the wider Asian region.

(Photos provided by Kwok Kian Chow)

When Chinese writer Lu Xun (1881-1936) first set foot in Japan in 1902, it was in Yokohama. Aptly therefore, the 8th Yokohama Triennale running from 15 March to 9 June has included “Wild Grass”, the title of a collection of Lu Xun’s writings from 1922-26, in its title: “Wild Grass: Our Lives”.

Between Japan and China and elsewhere

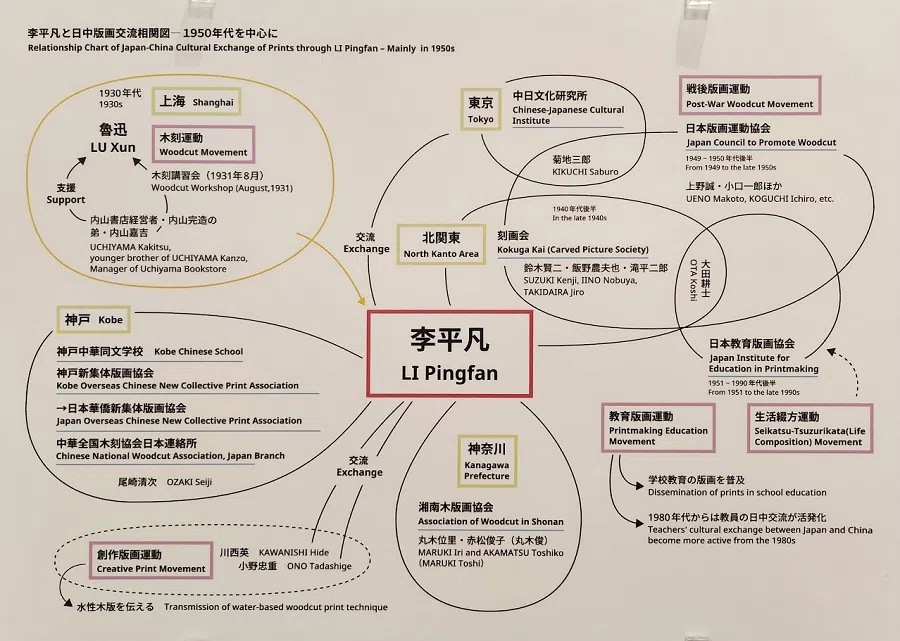

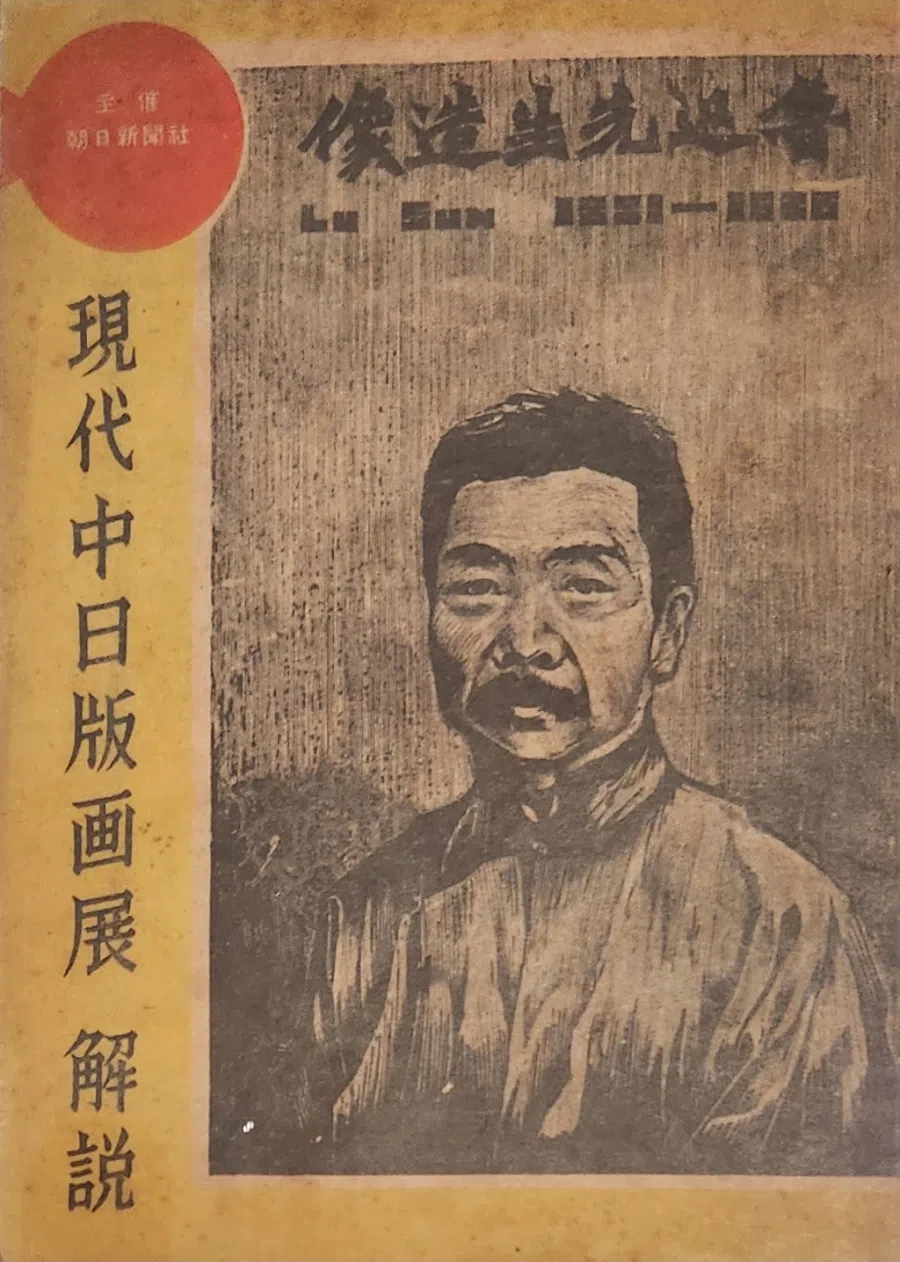

Just as the towering 20th-century literary figure is known for initiating the Modern Woodcut Movement in China, the triennale takes on the historical woodcut connections between Japan and China and also in more extensive areas within Asia, as the historical lynchpin between themes and venues in the triennale.

A lead-in to the woodcut works and history is the printmaker Li Pingfan (1922-2011), who had devoted his life to Japan-China exchange through printmaking amid the Sino-Japanese Wars and the Pacific War. Li lived in Japan until 1950. A war can be fought between countries, but art can unite artists and intellectuals of opposing nations through continued camaraderie.

In March, when I visited the Yokohama Museum of Art, the main exhibition venue, there was an inscription in Sámi (language of the descendants of nomadic peoples of northern Scandinavia) by Joar Nango on the facade of the museum.

The inscription read, “Neither following the route nor the rules.” These words serve as a unique and thought-provoking addition to the museum’s architecture. The phrase implies a sense of independence and individuality, encouraging visitors to break free from the conventional approach and think outside the box.

The woodcut print works and historical accounts are featured in the “Streams and Rocks” chapter of the triennale, located in the middle area of the upper floor galleries, overlooking the grand hall of the Kenzo Tange-designed museum. This chapter showcases “the outpouring of life force in the clash between advancing and thwarting,” as noted in the wall text by co-artistic directors Carol Yinghua Lu and Liu Ding, who are based in Beijing.

The exhibition flow “replicates the museum architecture… just as we have created a temple of doom in the revelation of daily life in the museum’s grand hall,” explained Lu to me during my visit to the museum.

One’s eyes circle the grand hall and encounters on the one side, Miles Greenburg’s monumental sculpture Mars (2022), a physical rendition of the artist’s performance standing on a pool of liquid, manifesting the tension of stillness and movement, solid and liquid, monumentality, and the moments.

... one immediately feels equal amounts of distress and hope and begins to relate the triennale and the artworks to the lifeforce of “wild grass” which always has a lingering melancholy.

Where distress and hope co-exist

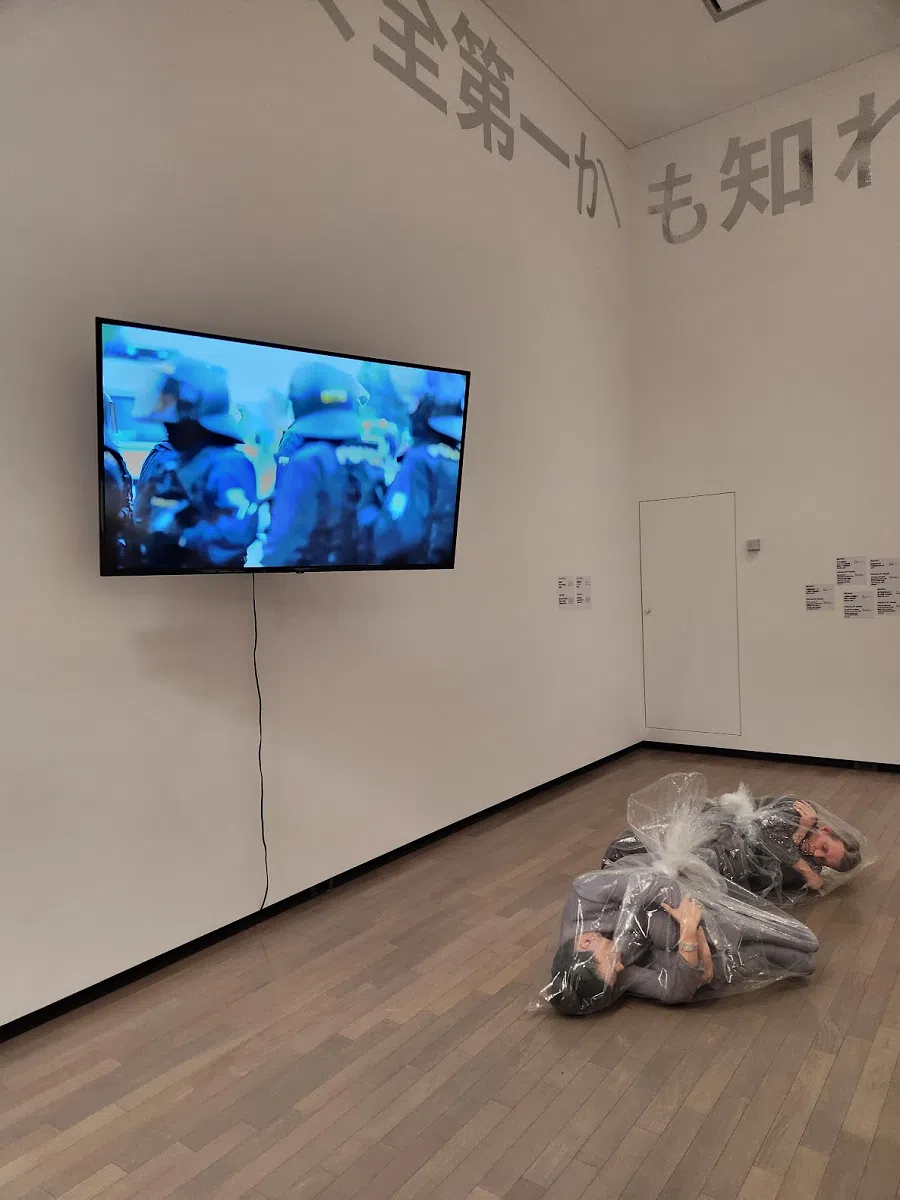

On the other side, one encounters Repeat After Me (2022) by the Open Group (Yuriy Biley, Pavlo Kovach, Anton Varga; Ukraine) on the huge monitor. In the video work Repeat After Me, artists utter sounds that emulate the machine guns, artillery and missiles of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Sandra Mujinga’s Ghosting (2019), a work of suspended blood-coloured textiles on the ceiling in the middle of the hall add to the tension between the resplendence of the hall and the fluidity of the works. “Fabrics weakened the monumentality of the structure,” commented Lu.

The brightly lit grand hall doesn’t give off a sense of doom. Carol Yinghua Lu explained to me that the grand hall and the triennale as a whole are about living with what we have, just like how “the rocks can never stop the streams”. As a result, one immediately feels equal amounts of distress and hope and begins to relate the triennale and the artworks to the lifeforce of “wild grass” which always has a lingering melancholy.

Lu Xun began the foreword to Wild Grass with: “When I am silent, I feel replete; as I open my mouth to speak, I am conscious of emptiness. The past life has died. I exult over its death, because from this I know that it once existed.”

While these were coincidental, the Yokohama Triennale appears current in signalling social advancements in recognising gender diversity and equality...

Not subject to social categorisation

At the doorsteps of the Yokohama Museum of Art, an undulating queue line leads to the entrance. A visitor walks through the line (one could choose to walk straight in without following the line), only to realise that it is an artwork — Barriers (Stanchions) (2017-2024) — by Puppies Puppies (Felix Gonzalez-Torres), comprising a small signage at the end of the queue that reads: “For LBGT immigrants, deportation can be a death sentence. It’s time for a new approach.”

Another Puppies Puppies’s work is featured at the BankART KAIKO venue of the triennale: Untitled (Portrait of Japanese Transgender History, American Transgender History, and Jade Kuriki-Olivo) (2024), which comprises a timeline of the transgender community in Japan and the US.

As if updating the timeline, it happened that during the week of the Yokohama Triennale opening, on 14 March 2024, the Sapporo High Court and Tokyo District Court ruled that the ban on same-sex marriage was unconstitutional. On 27 March, the lower house of Thailand passed a bill to give legal recognition to same-sex marriage.

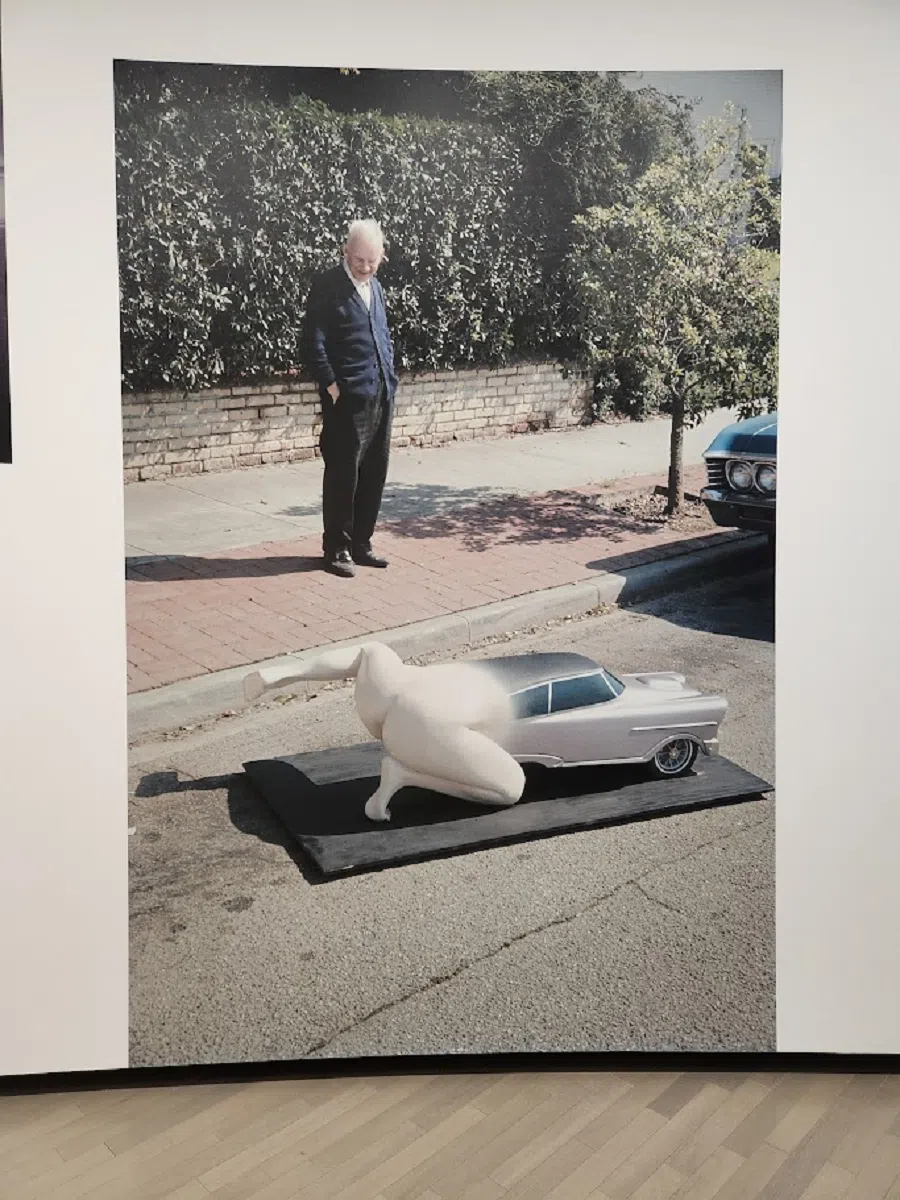

While these were coincidental, the Yokohama Triennale appears current in signalling social advancements in recognising gender diversity and equality, just as the cheerful Human Prototype (2020) by Pippa Garner placed at the centre of the grand hall celebrates the triumph of how one’s existence should not be subject to social categorisation.

The triennale artistic directors underpin the overall theme of Wild Grass as a necessary struggle against the weight of social structures, finding enough buoyancy for personal freedom through art and literature.

Finding personal freedom through art and literature

A further anchoring of literary and aesthetic affinity between China and Japan through Lu Xun and the woodcut is how Lu Xun was inspired by Kuriyagawa Hakuson (廚川白村, 1880-1923)’s Symbol of Depression (苦闷的象征), which Lu Xun translated as he penned the proses and poems that would later be anthologised into Wild Grass.

Kuriyagawa Hakuson looked at the expressions of depression induced by social conditions as the source of great literature. The triennale artistic directors underpin the overall theme of Wild Grass as a necessary struggle against the weight of social structures, finding enough buoyancy for personal freedom through art and literature.

The “Streams and Rocks” chapter is later followed by the “Symbol of Depression” chapter, the very title of Kuriyagawa Hakuson’s book Lu Xun translated. Here, the exhibition takes a turn towards materiality, not unrelated to the symbolist aesthetics suggested by Kuriyagawa Hakuson’s text, linking the triennale to the broader discourses on aesthetics.

By this very flow and chapter titles, the artistic directors have approached this triennale project like creating an artwork as well as writing a book.

By this point, the triennale has built up layer by layer from the architectural and historical framework of the Yokohama Museum of Art, a global and personal reality in the opening chapter, the Lu Xun, Kuriyagawa Hakuson, woodcut, and symbolism middle chapters, to closer affiliations with contemporary art practices in the “Dialogue with the Mirror” chapter and then “Fires in the Wood”. By this very flow and chapter titles, the artistic directors have approached this triennale project like creating an artwork as well as writing a book.

Not taking things lying down

Apart from Puppies Puppies, works by the same artist are also repeated in different galleries or venues in the triennale. One prominent example are the works by Josh Kline. Entitled with “occupations” such as administrator and lawyer, found affiliation with the widely popular David Graeber’s book On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs: A Work Rant (2013) which is listed among the bibliography called Dictionary of Life featured in the grand hall.

The sarcasm and humour of Josh Kline’s works are obvious, and the repetition in different galleries further pronounces the “bullshit” situation likely to find identification with some, if not many, of the visitors.

The Chinese take to Josh Kline and David Graeber is The Tangpingist Manifesto (躺平者宣言), also known as “laydownism”; and as the expression suggests, it is about giving up on diligent work and career advancement. This leads to the question of anarchism, which apparently contradicts the tightly curated and structured triennale, let alone in Kuriyagawa Hakuson’s line, “The outpouring of the power of our lives to open up the future.”

The various sites of the triennale are conveniently connected by the Minatomirai Line, Yokohama’s main subway line. This same line also connects to Chinatown and Yamashita Park. On the first encounter with the Former Daiichi Bank site of the triennale, it had the feel of documenta 15. But wait, looking at the sparkling glass panel, the sleek chandeliers, squeaky clean floors, and how about this label on the table that says to put the books back in their original position after viewing, I knew I was in Japan unmistakably.

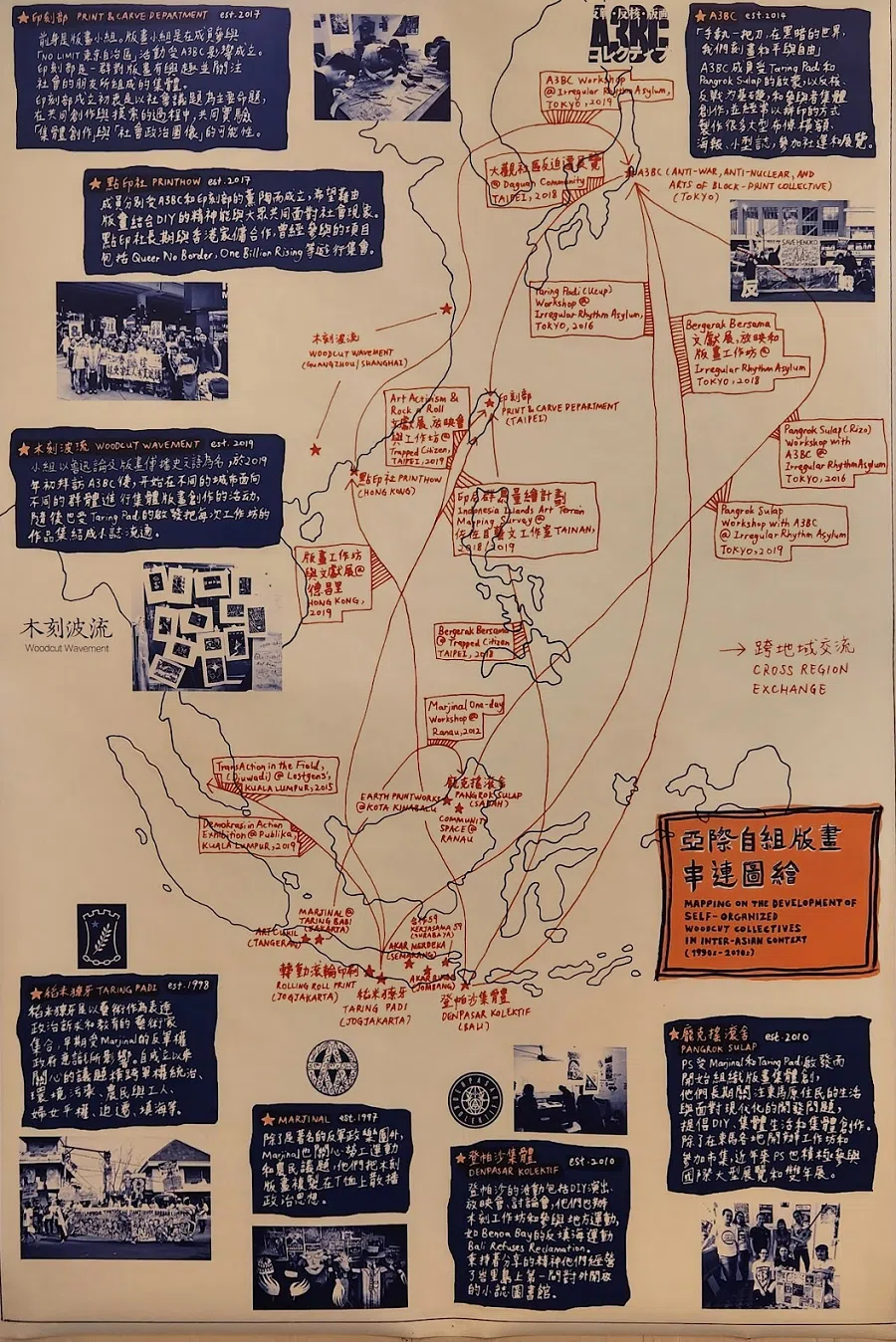

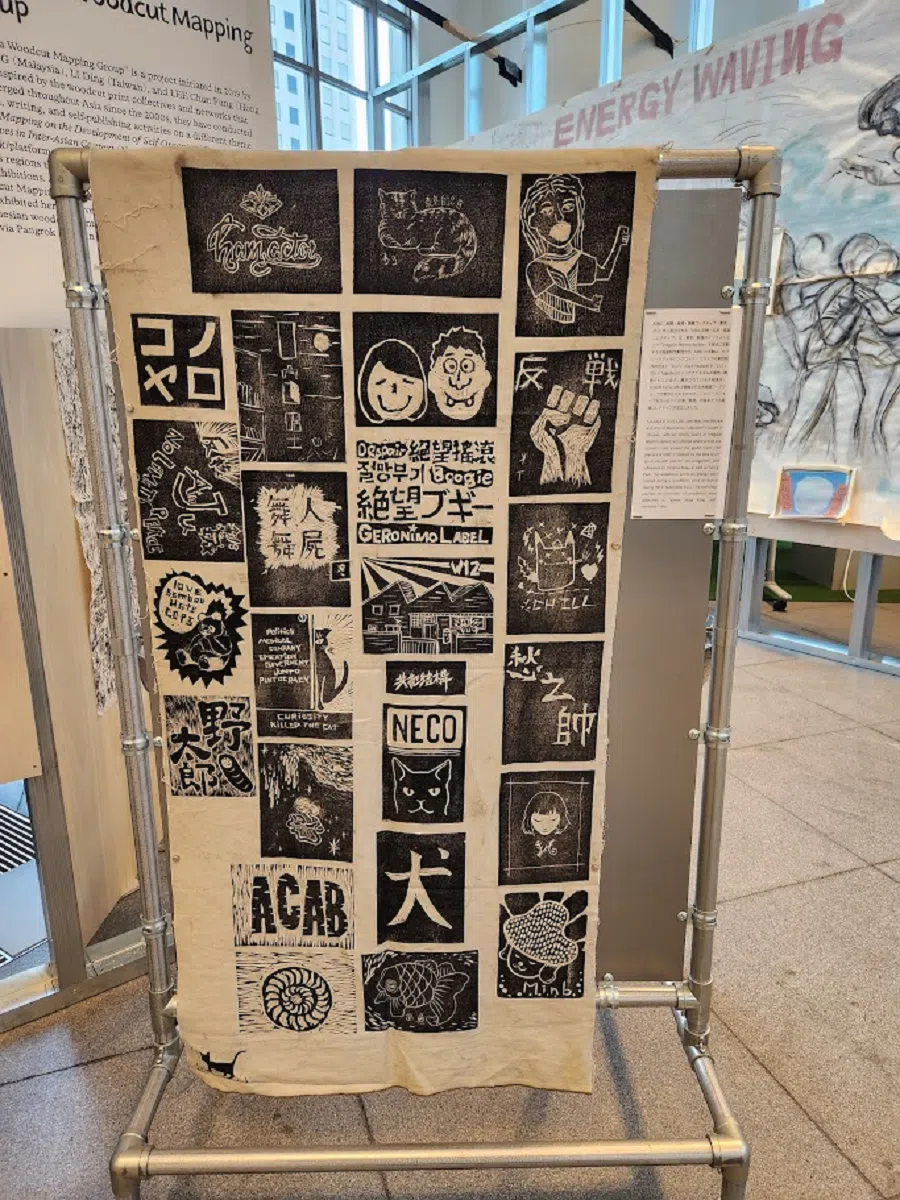

The Former Daiichi Bank venue can be a standalone, but also an important expansion of the individual liberty theme underpinned in the main museum site to include the art collectives. Woodcut is an important link with the Yokohama Museum main site here, particularly in the Mapping the Development of Self-Organized Woodcut Collectives in the Inter-Asian Context (1990s to 2010s), a project initiated by Krystie Ng, Li Ding, and Lee Chun Fung of Malaysia, Taiwan, and Hong Kong respectively. Featured in the triennale is also an account of how the activities of Taring Padi, a collective based in Yogyakarta, spread to other parts of Asia through the efforts of Pangrok Sulap (Kuala Lumpur) and A3BC (Tokyo).

In Lu’s reflection in our conversation, “Art should have a dialogue with social reality.”

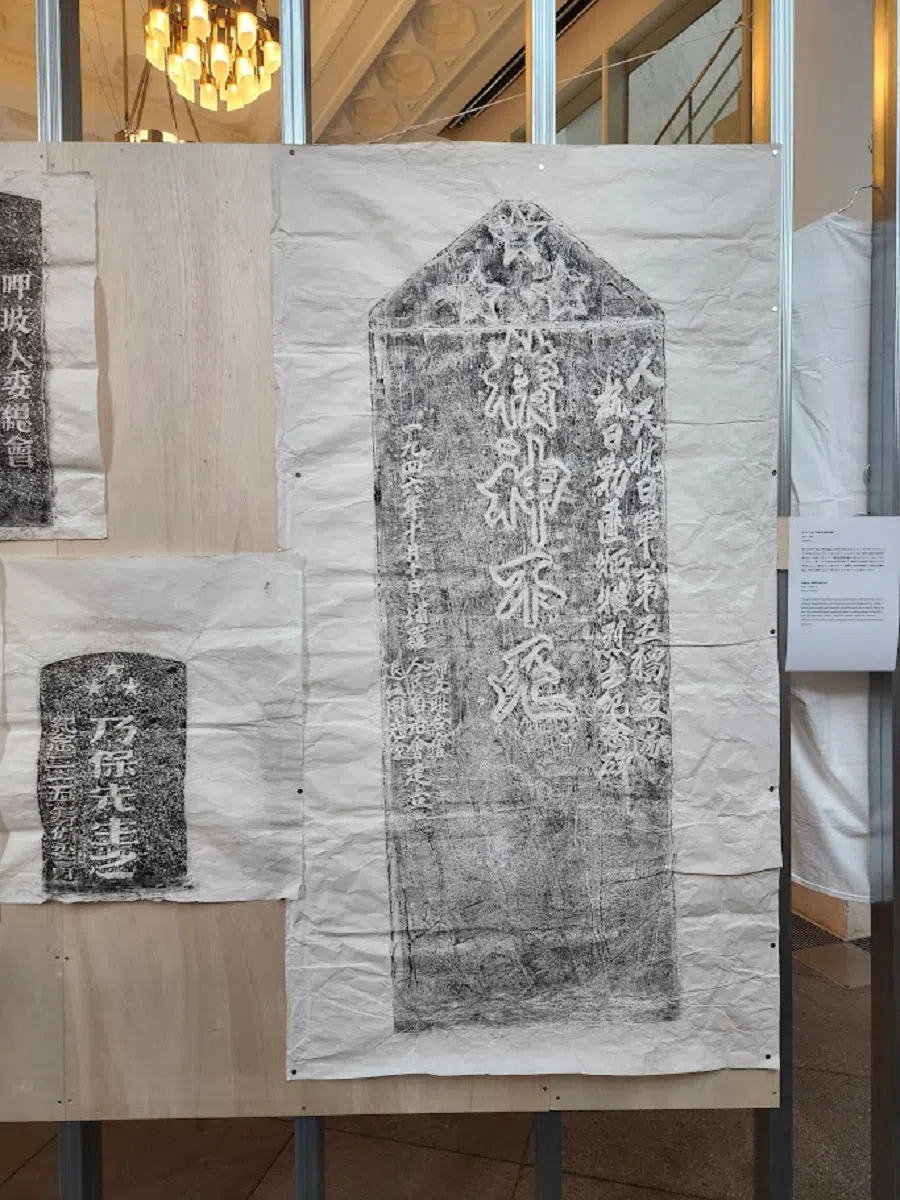

Rubbings of steles relating to the Second World War are a part of the memory and archiving practices of the Lostgens’ Contemporary Art Space in Kuala Lumpur. Many are imprints of tombstones of those who sacrificed their lives resisting the Japanese invaders. One without naming individuals commemorated a group resistant military unit sacrifices read “monument to the martyrs who died in the war against Japanese aggression and brigand suppression — long live the spirit”.

I reconnected with some of the artworks in the main museum venue, in particular Your Bros Filmmaking Group’s Dorm. While there is a historical event as background to the work, that of a demonstration in 2018 by Vietnamese women factory workers locking themselves up in their dormitory in Tainan to demand better treatment, the instalment created a dormitory environment for visitors to have engagements with the everyday objects and to feel being a part of a migrant workers dormitory environment. This further enhances the adherement to realities emphasised in the triennale. In Lu’s reflection in our conversation, “Art should have a dialogue with social reality.”

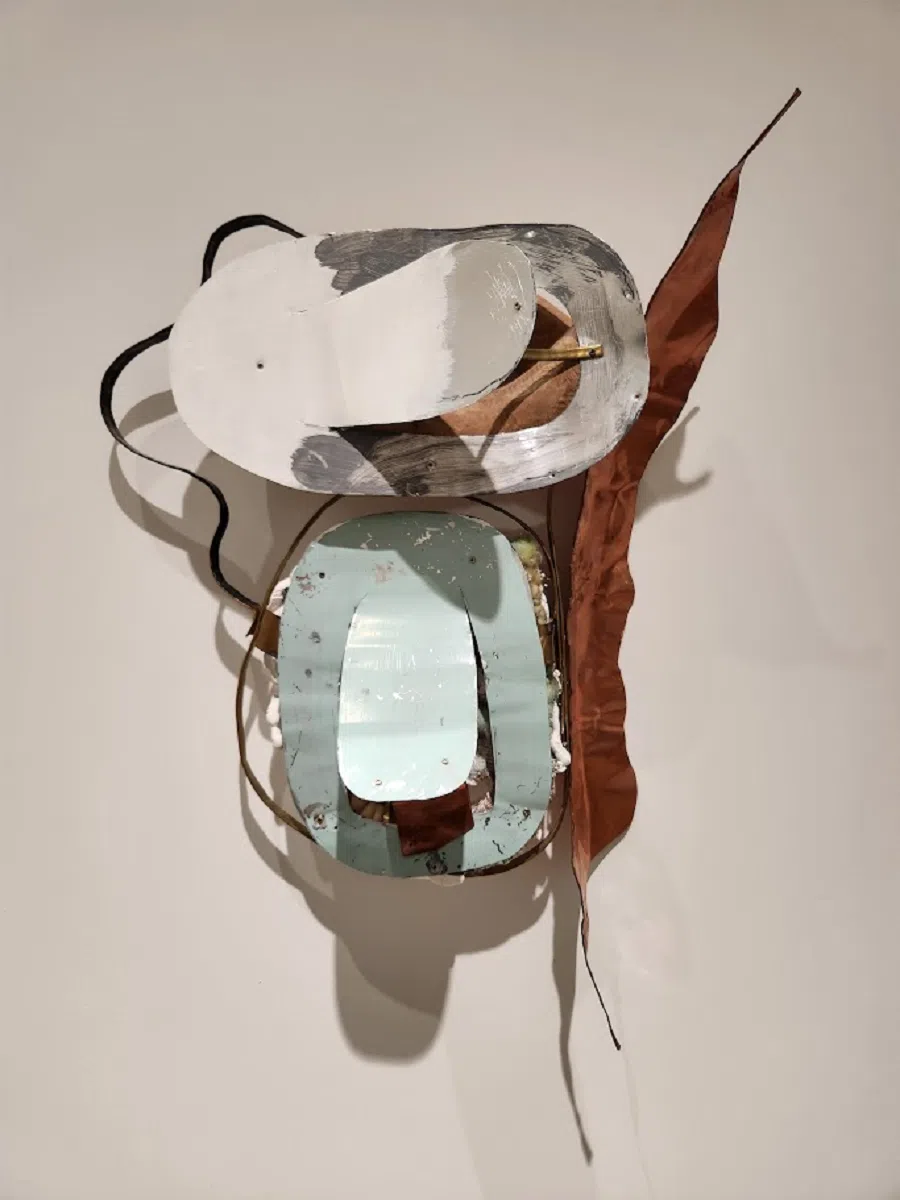

In Pyae Phyo Thant Nyo, A Story of Our Lives (2024), “the mixture of metal, plants, and man-made objects seems to decay and disintegrate, while at the same time, everything seems to come together and transform into a new form of life.”

Destruction while also bringing hope and construction

The exhibition is carefully curated and structured to showcase destruction while also bringing hope and construction. Achieving this requires viewers to be mindful, diligent, and engaged at various levels, and ideally over several visits. Carol Yinghua Lu personally took me through the main venue and through histories and contemporary art to reflect on the heavy burden of social structures.

Despite this, the works also offer a curious sense of hope and stability at a personal level. Are the feelings of precarity and despair similar in the 2020s world to what they were in 1920s China? Yes, in the sense that one must continually seek their own agency. As Kuriyagawa Hakuson said, “The outpouring of the power of our lives to open up the future.” I was reminded of a famed line from one of the key primogenitors of anarchism, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865), “It is liberty that is the mother, not the daughter, of order.”

I spent several hours looking at the artworks in the main venue of the Yokohama Triennale. Reluctantly, I stepped out of the museum as it was closing time. As I was leaving, I ran into the museum director, Kuraya Mika, who was finishing her workday.

We had a brief conversation standing close to Puppies Puppies’s Barriers (Stanchions), where I told her how lucky the residents of Yokohama were to have the opportunity to return again and again to take in the triennale at their own pace. The Yokohama Triennale is like a well-structured book with multiple chapters. In today’s world, people do not read a thick book from beginning to end. Instead, they navigate through chapters, stories, ideas, and sentences to discover what inspires them. The Yokohama Triennale provided an exciting platform to do just that.