China’s pension plan faces prospect for change or going bust

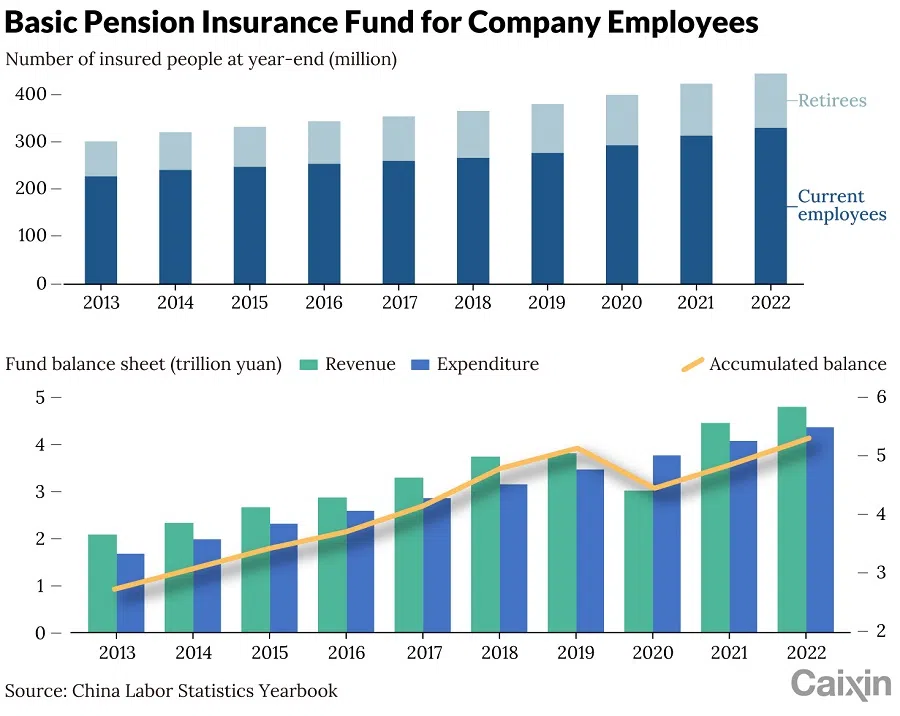

As the working-age population shrinks and the number of retired workers grows, the younger population is increasingly burdened by a system where current employee contributions fund payments to retirees. China’s pension plan for employees of state-owned and private businesses is now facing the likelihood of major reforms or the prospect of going broke.

(By Caixin journalists Zhou Xinda, Tang Hanyu and Denise Jia)

China’s pension plan for employees of state-owned and private businesses is facing the likelihood of major reforms or the prospect of going broke.

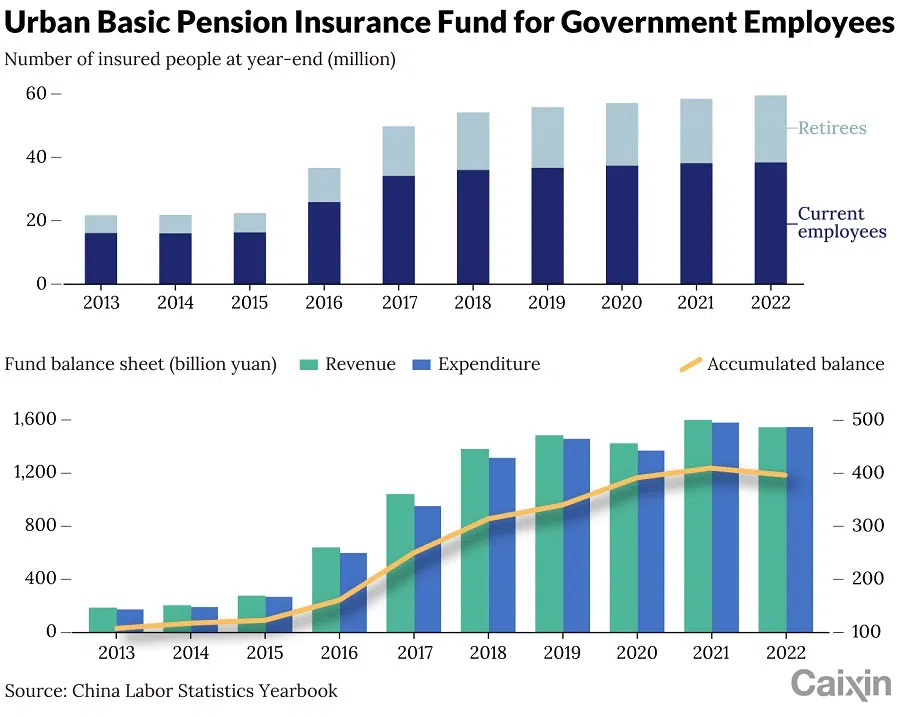

Demographic shifts are adding pressure on the system. Under the pension plan for so-called enterprise employees — which covers non-government workers — current employee contributions fund payments to retirees. As the working-age population shrinks and the number of retired workers grows, the younger population is increasingly burdened, weakening their incentive to participate in the retirement programme. According to a 2019 report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, basic pension assets for urban employees may be depleted by 2035. (Rural workers are covered by a separate retirement programme.)

In 2022, China’s population fell for the first time in 61 years, with the elderly (aged 65 and older) making up 14.9% of the overall population and the dependency ratio — the elderly as a percentage of the working population — exceeding 20%. In 2019, there were 2.65 workers contributing to enterprise employee pension insurance each enterprise retiree receiving payments. By 2050, that ratio is projected to decline to 1.03 workers per retiree.

At a Caixin forum on the elderly care industry last month, government officials and experts discussed potential solutions for shoring up pension fund. Suggestions included raising the retirement age, extending the contribution period and encouraging workers to contribute to their private pension accounts.

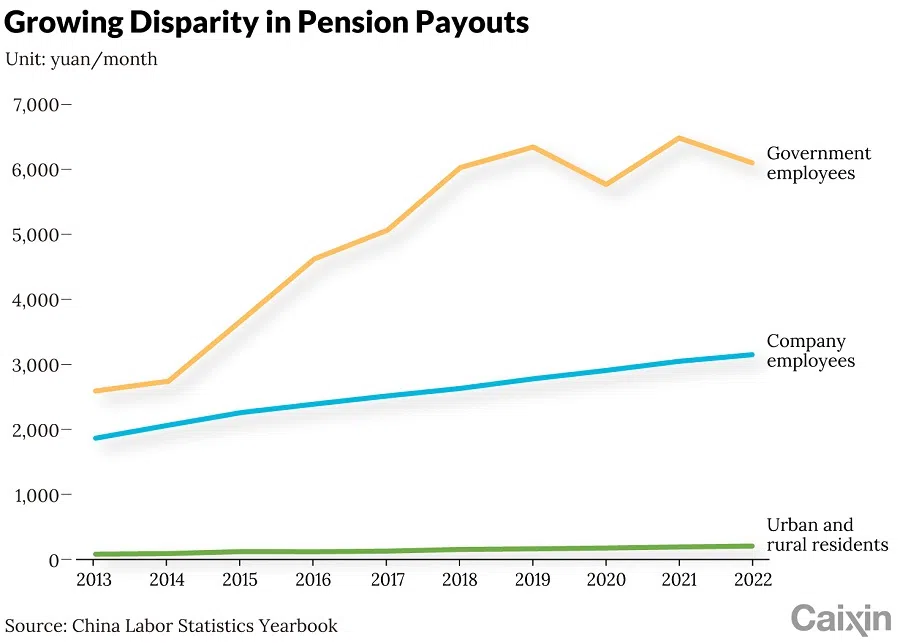

China has two retirement systems — one for government employees and the other for enterprise workers. Retirement payments vary widely between the two plans.

The average monthly pension for former government employees more than doubled to 6,099.80 RMB (US$840) in 2022 from 2,741.50 RMB in 2014, according to the China Labor Statistics Yearbook. Over the same period, pay for retirees of enterprises — which include private and state-owned companies — rose just 52.6% to 3,148.60 RMB from 2,063.90 RMB.

... enterprise employees get less than half of their pre-retirement income paid out by a separate pension plan backed by both the state and personal contributions.

Beyond the disparity in payments, government workers do not make contributions toward their retirement insurance — as enterprise employees must do to receive future benefits. The fiscal-backed pension system can guarantee government workers receive more than 80% of their pre-retirement salaries after they reach retirement age. By contrast, enterprise employees get less than half of their pre-retirement income paid out by a separate pension plan backed by both the state and personal contributions.

Raising the retirement age to 65 by 2045, and aligning retirement ages for men and women through gradual increments, is seen as a long-term goal.

Early retirement

China’s statutory retirement age is 50 for female workers, 55 for female managers and executives, and 60 for male employees — a standard set in 1951 when life expectancy was much lower. The minimum contribution period of 15 years to receive benefits, set in 1997, remains unchanged.

The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security acknowledges that delaying retirement will maximise human resources, increase post-retirement income,and ease pension fund pressures while promoting system sustainability. China’s average retirement age is below that of developed countries, which also faced resistance before revising their pension schemes.

Delaying the retirement age could lead to a reduction in the number of retirees to 210 million by 2050, from 278 million in 2019. The retiree dependency ratio could improve to 1.53:1 from 1.04:1. The change would extend the life of the pension fund by seven years before its assets are depleted, according to experts.

Pushing back the retirement age has been discussed for more than a decade. The Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party in 2013 proposed a gradual increase in the age to qualify for benefits. In 2015, the then-Minister of Human Resources and Social Security, Yin Weimin, said a plan to raise the retirement age would be unveiled in a year.

In 2020, the extending the retirement age was included in the 14th Five-Year Plan. With two years left remaining on the timeframe, no proposal has emerged.

A former Human Resources Ministry official told Caixin that a more moderate retirement delay plan has been made internally but remains unpublished because of social resistance. An internal meeting in 2023 emphasised accelerating these reforms, another person close to the matter told Caixin.

The complexity of changing the retirement age involves balancing population structure, labour supply and intergenerational equity. Mo Rong, former head of International Labor Security Institute of Human Resources Ministry, noted that Japan and South Korea took more than a decade from legislation to implementation — longer than the process took in the US.

A consensus among policymakers and academic experts calls for a gradual delay. In 2016, Yin said the retirement age could be pushed back a few months each year.

Leaving the decision of when to retire to employees is another option. After reaching the statutory threshold of the earliest retirement age, workers could choose to retire earlier or later. Higher pension payments would be offered as incentives for employees to delay their retirements.

Germany and the US have gradually raised retirement ages to 67, incorporating flexible options. China may need to accelerate its pace to keep up with demographic changes, experts say.

Unifying the retirement age of men and women to 60 should be a priority, starting with female employees at government entities and large state-owned enterprises that provide better benefits and pensions, experts suggested.

Reforming retirement age also involves aligning benefits for women with those in Europe and the US to ensure equitable treatment in education, employment and childcare, some experts say.

Raising the retirement age to 65 by 2045, and aligning retirement ages for men and women through gradual increments, is seen as a long-term goal.

Speaking at the Caixin forum, former central bank governor Zhou Xiaochuan cautioned against raising the retirement age significantly due to inevitable declines in physical function and productivity, stressing the balance needed to maintain business competitiveness.

The 15-year minimum contribution period is considered outdated and insufficient given demographic and economic changes.

15-year contribution not enough

In addition to raising the retirement age, experts have also suggested increasing the minimum period of pension contribution by employees. The 15-year minimum contribution period is considered outdated and insufficient given demographic and economic changes.

The enterprise employee pension insurance fund, launched in the late 1990s, initially set a low contribution period to accommodate laid-off workers during state-owned enterprise reforms and to quickly expand coverage. However, this short-term fix has led to systemic issues, such as a high payment burden and weak incentives, especially as the economy faces downward pressure and flexible employment grows. The current 15-year contribution period often leads to early retirement and insufficient pension funds, creating a financial gap as life expectancy increases.

The minimum contribution period is expected to align more closely with international standards, typically over 30 years. Regions like Guangdong have already adjusted their plans, setting contribution periods of 30 years for male workers and 25 years for female workers starting in 2023. Scholars suggest that a 25- to 30-year contribution period would be more reasonable.

... long-term structural reforms are needed to boost incentives for people to contribute to their individual pension accounts. — Zheng Bingwen, Director, World Social Security Research Center, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

Supplement with personal pensions

To address the challenges of an ageing population and ensure the sustainability of the pension system, experts emphasise that merely raising the retirement age and extending the contribution period are not enough, as such measures do not expand the pension fund income sources.

For a fundamental solution to fill the shortfall of the pension fund, long-term structural reforms are needed to boost incentives for people to contribute to their individual pension accounts, said Zheng Bingwen, director of World Social Security Research Center at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

China officially introduced the personal pension fund programme in November 2022, allowing people from 36 pilot cities and regions to set up accounts. Annual contributions up to 12,000 RMB per account are exempt from income tax, giving individuals an incentive to put money in them. Account holders can invest their contributions in approved products, including bank deposits, mutual funds, wealth management products and pension insurance.

The number of personal pension fund accounts surged last year, but the scheme designed to shore up China’s pension system remained hamstrung by low contributions and a lack of investment.

More than 50 million people had set up personal pension accounts as of the end of last year. However, only around one-fifth of people with personal accounts had contributed to them by the end of June 2023, according to Zheng. Furthermore, the average individual contribution of about 2,000 RMB was well short of the annual limit of 12,000 RMB per account.

The lack of transparency in China’s pension system is also a significant barrier to individuals participating in personal pension plans.

To encourage more employee to contribute to their personal pension accounts, Zhou suggested to mandate a matching of employees’ contributions by the employers to the personal accounts, a practice similar to China’s housing provident fund as well as the US’s 401K retirement plans.

The lack of transparency in China’s pension system is also a significant barrier to individuals participating in personal pension plans. Zhou noted that many retirees are surprised by how much money they receive from their pension, a problem stemming from limited policy interpretation. This uncertainty, coupled with a lack of understanding of tax incentives and the differences between personal pensions and direct savings, leaves people unsure about their financial future, Zhou said.

Zhou emphasised the need for individuals to have a clear pension plan before retirement to determine if they will have sufficient funds. “If we don’t know how much basic pension we will receive, how can we expect to actively participate in the personal pension plans?”

He pointed out that past studies on the pension system have focused more on macro-level issues, neglecting how the system impacts individual financial planning and incentives.

To address this, Zhou proposed enhancing the transparency of pension calculation criteria, enabling individuals to predict their pension benefits based on their contributions. Providing real-time access to personal account balances would allow people to adjust their financial plans throughout their lives, ensuring lifetime financial security, the former central bank governor suggested.

He stressed that policy formulation should clearly provide three expectations: a basic pension funded by the state equal for all retirees, incentives varying by contribution period, and the option for individuals to choose additional products like personal pensions.

Cheng Siwei contributed to this report.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “Cover Story: China’s Pension Plan Faces Prospect for Change or Going Bust”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)