A eulogy, intimate memories and a flawed piece of calligraphy

I wonder if the basic education of practising calligraphy with a brush still exists today?

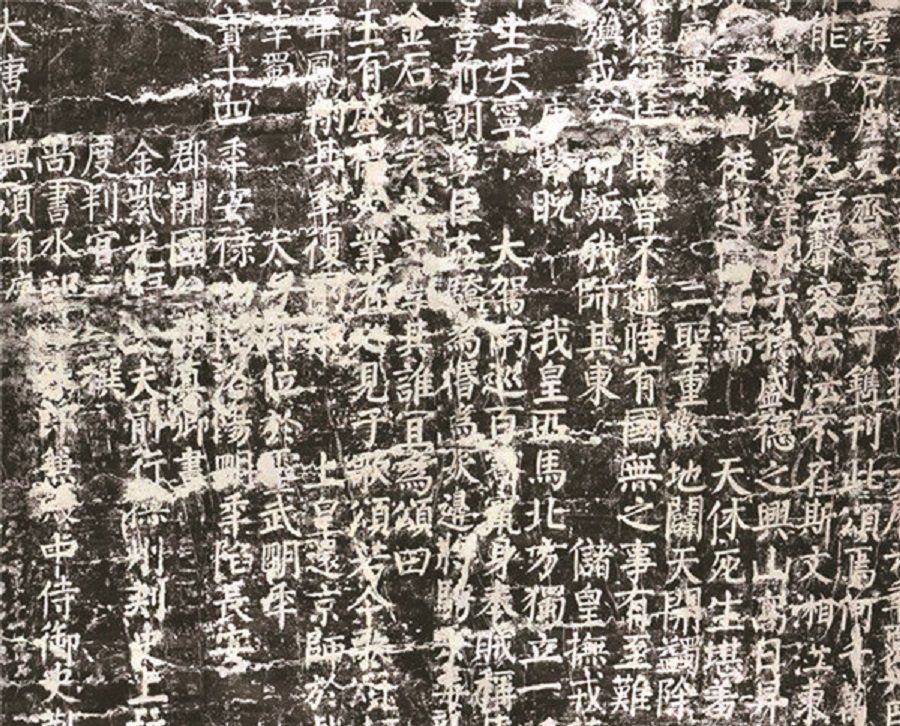

In my childhood, every school child's education journey started with rigorous brush calligraphy training. It was based on the highly structured regular script (楷书) of the Tang dynasty, which meant that there was no escape from masterpieces like Ouyang Xun's Jiu Cheng Gong (《九成宫》), Liu Gongquan's Xuan Mi Ta Bei (《玄秘塔碑》), and Yan Zhenqing's Da Tang Zhong Xing Song (《大唐中兴颂》, Eulogy on the Prosperity of the Tang Empire).

Children aged four and five would hold soft calligraphy brushes and practise writing on calligraphy tracing paper, strictly following the rules of each and every stroke - such practice sessions were taken very seriously. In my truest memory, none of us really understood the point of Father's strict regular script calligraphy training.

In my memories, that was also one of the most intimate moments my father and I shared.

Calligraphy was just homework that had to be submitted - I would often hastily grab my brush and scribble on the papers when Father was just about to check them. I purposely chose characters that were simple and did not have many strokes - "person" (人 ren), "one" (一 yi), "up" (上 shang), and "big" (大 da), just to name a few.

Of course, Father knew what I was up to! Thus, he would often sit behind me, grab my hand, and fill up each cell of the tracing paper with me, a stroke at a time. In my memories, that was also one of the most intimate moments my father and I shared: I could feel my father literally breathing down my neck, and the warmth from his palm firmly gripped around mine.

When I went to secondary school, calligraphy was also part of my Chinese lessons - even compositions had to be written using a calligraphy brush. I fell in love with literature then and had an interest in writing. However, I always felt that my hand was in the way of the flow of my creative juices as I had to write with a brush. I also couldn't understand why we had to write our compositions with a brush. Were compositions training our literary skills, or were they training our penmanship instead?

I've long been confused about writing my own sentences with a brush. It was not until I went to graduate school, had lessons at the National Palace Museum, and saw the great works of master calligraphers of the different dynasties - Wang Xizhi, Yan Zhenqing, Su Shi - that I suddenly understood. They too, were writing their own sentences with calligraphy brushes.

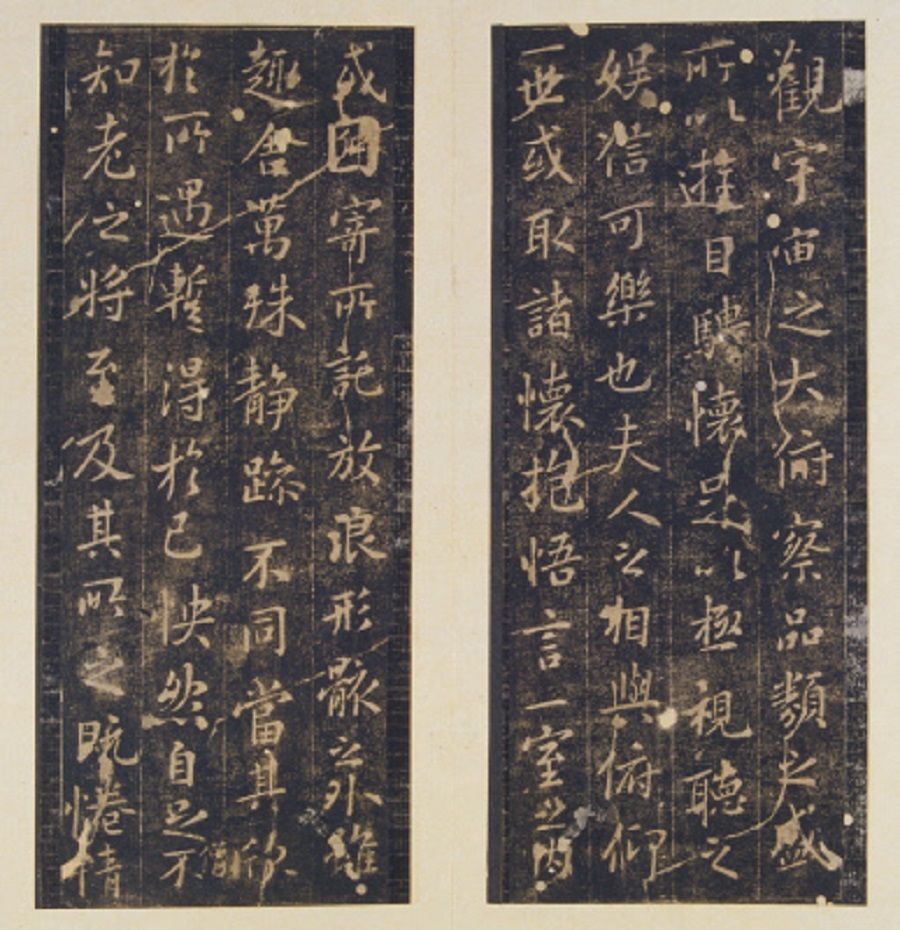

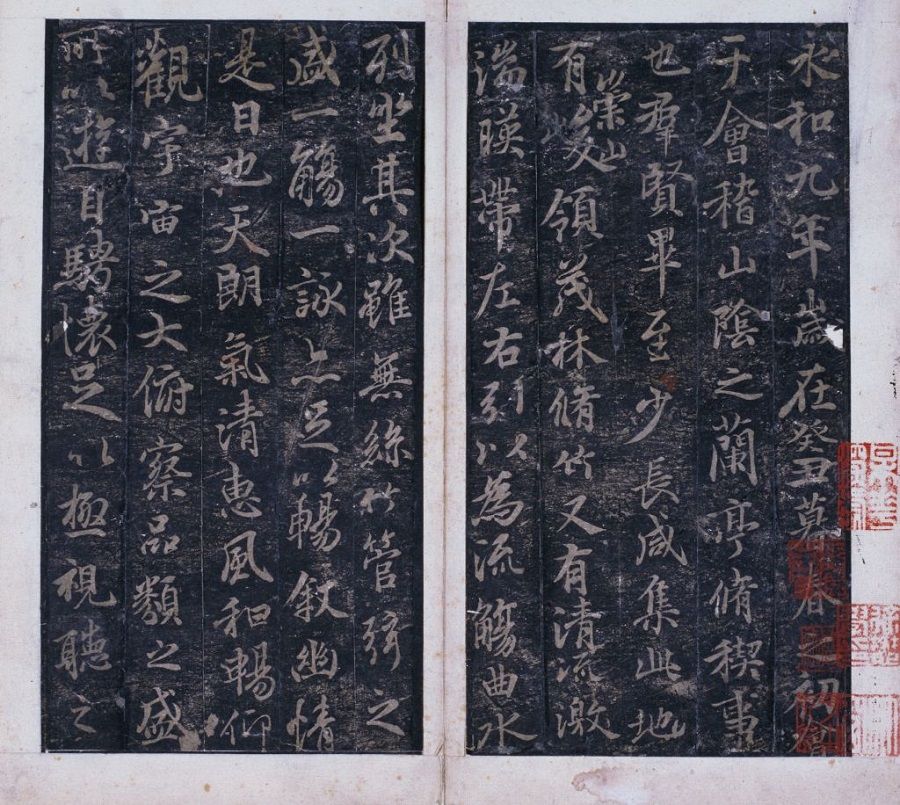

There are various versions of Wang Xizhi's Lanting Xu (《兰亭序》, Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection), but they are all reproductions of his work that had surfaced after the Tang dynasty - none of them are original.

Evidently, no matter how much Emperor Qianlong praised them, it would be hard for these works to possess the original calligrapher's state of mind when he spontaneously wrote the piece. A line reads: "On this day, the sun is beaming and the air is fresh. How soothing is the warmth of the spring breeze! I look up and see the grandeur of the universe. I look down and see the creatures that fill the Earth..."

Whenever I admired shenlong ben (神龙本) (the version of Lanting Xu reproduced by Feng Chengsu) and dingwu lanting tuoben (定武兰亭拓本) (the version of Lanting Xu reproduced by Ouyang Xun), I had to further imagine how the calligrapher Wang Xizhi first translated his emotions into words, and how all of that was re-interpreted into all those permutations of strokes and dots that make up each character.

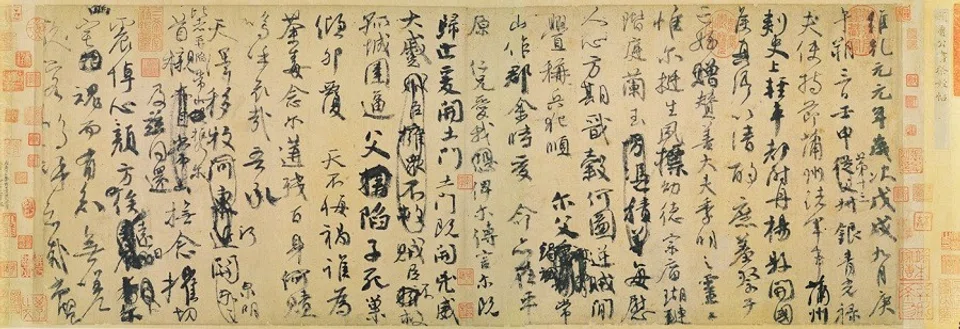

The Lanting Xu is described as the most outstanding semi-cursive script (行书) in Chinese calligraphy. But it has lost its "authenticity" as it has seen many reproductions. However, when I looked at the original semi-cursive script that is next in line, the Ji Zhi Wen Gao (《祭侄文稿》, Eulogy for a Nephew) by Yan Zhenqing, I immediately understood the wonders of calligraphy.

Ji Zhi Wen Gao is a eulogy written by Yan Zhenqing of the Tang dynasty when he found his nephew Yan Jiming's decapitated head at the battlefield. The An Lushan Rebellion had killed over 30 people of the Yan family at once. Yan Jiming was a promising young man who was held hostage by the enemies in an attempt to force his father Yan Gaoqing to surrender. The father refused, and his son was beheaded. The rebellion was tragic and the gruesome death of Yan Zhenqing's nephew too much to bear.

Yan Zhenqing turned heart-wrenching sorrow into Ji Zhi Wen Gao through his ink brush. His strokes were imperfect and flawed; the scripts were dotted with blotches of corrections and characters that he had struck out. This semi-cursive script second only to the most outstanding, is in fact, an extraordinary historical document. If Yan Zhenqing's Da Tang Zhong Xing Song (《大唐中兴颂》, Eulogy on the Prosperity of the Tang Empire) is a standard and official monument, his Ji Zhi Wen Gao is then an intimate and spontaneous piece that speaks of the sufferings of his lost.

I want to pick up the brush that my father so wished that I would pick up and write about what's in my heart. I want to write in the language of my era and about the beaming sun and the fresh air. If there comes a day when I would witness the capturing of a city and a father who has fallen and a son who has been killed, what would I write?

It is not only these

That can be remembered

Or can be forgotten

Apart from true love

That we can write into poems

There is nothing else I wish to speak for us

Even if I'm holding an ink brush, I only want to write the words of my era.

Related: Picking up an ink brush amid the pandemic, what do I write? | Powerless, helpless and downtrodden: The state of Chinese literature in this pandemic | Yuelu: 40 years of longing for a thousand-year-old Chinese academy | Chiang Hsun: The freed poet in rainy spring, by the Yangtze | Chiang Hsun: How great a mark of rebellion it is to hold an ink brush