Geopolitics is the biggest threat to China-US relations, not trade or tech wars

Contrary to doomsday predictions, the US-China trade and tech relationship is actually rather sturdy. After all, it was their economic and trade complementarity that brought them finally to agree on a phase one trade deal, and against all odds, US direct investments into China grew by 6% (from a year earlier) in the first half of the year. Geopolitics and volatile brinkmanship in the name of power relations could instead be the greater threat. But between Trump and Biden, which is the lesser evil?

China-US relations is undoubtedly the hottest topic now. Before the coronavirus outbreak, the two largest economies of the world were already knee-deep in a trade war and a tech war. Not only did the US bypass the World Trade Organization and impose unilateral tariffs on a rising China, but it also implemented a series of tough restrictions in the technology sector. These measures aimed to derail China's "Made in China 2025" plans, namely by putting Chinese high-tech companies such as Huawei and ZTE Corporation on its sanctions list.

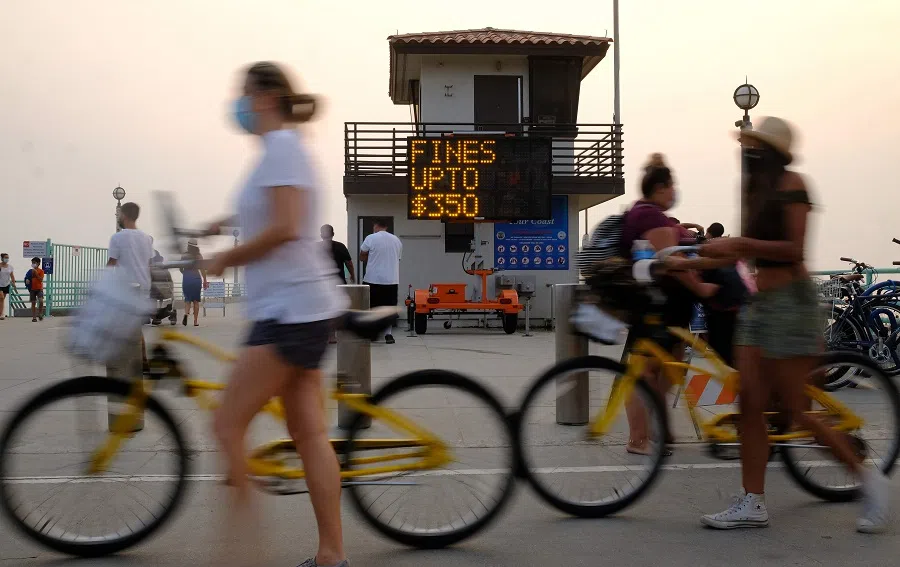

This year, the global spread of the Covid-19 pandemic has made matters worse: both sides have locked horns over the origin of the virus, failure to disclose information, the World Health Organization and other issues. Such bickering has also magnified geopolitical issues about Taiwan, the South China Sea, and the Indo-Pacific region. Some observers even suggest that the US and China have already started the process of totally decoupling from each other or are in the midst of a new Cold War. People are increasingly worried if such brinkmanship would put Asia-Pacific countries in a dilemma of choosing between the US and China.

He (Trump) believes that the US's enormous long-term trade deficit with China resulted from unfair trading practices and has led to unemployment and financial difficulties in the US.

Is the US-China trade and tech relationship as fragile as it seems?

Then again, a look back at how the US-China trade and tech wars have played out over the past four years under the Trump administration shows that while US-China competition has been intense, there remains a bottom line to the attacks. Globalisation and interdependence have made it difficult for the trade and tech wars to escalate into a complete decoupling from each other. And as the US presidential election draws near, China-US relations could face a new "window period" of uncertainty.

Trump has been wanting to play the "trade war card" against China since the 2016 elections. He believes that the US's enormous long-term trade deficit with China resulted from unfair trading practices and has led to unemployment and financial difficulties in the US.

Trump worked to fulfil his election promise the moment he assumed office. Not only did he hire hawkish economists like Peter Navarro as the assistant to the president and director of the Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, but he also started trade negotiations with the Chinese. The negotiations got increasingly intense and concluded with the US imposing punitive tariffs on Chinese goods from 2018 onwards. China immediately retaliated by imposing additional tariffs on US goods, marking the start of the China-US trade war. Although both sides managed to reach a consensus once, the China-US tariff war soon worsened in 2019. It was not until a phase one trade deal was signed early this year that the trade war came to a temporary truce.

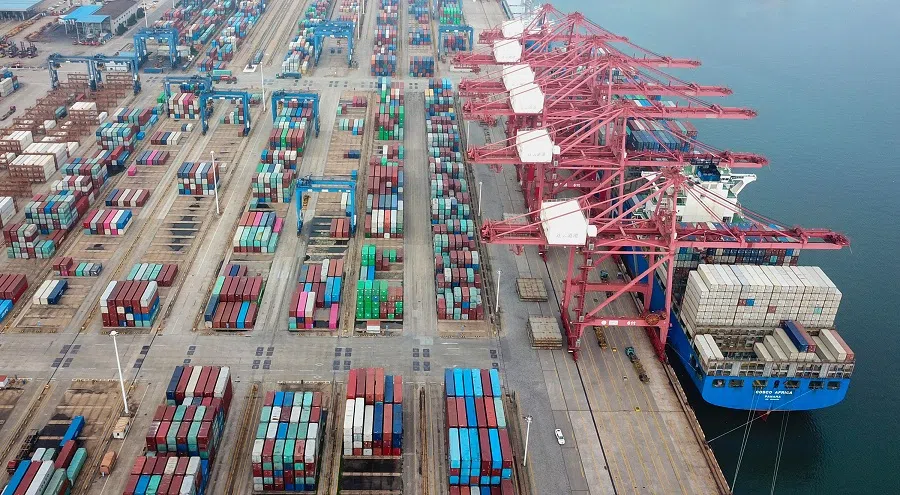

Although the pandemic has made implementing the deal challenging, trade volumes between China and the US remain massive and both countries are still each other's major trading partners.

Based on the development of the trade war, while US-China competition has been extremely intense with both sides trapped in major disagreements, the huge complementarity of their economies and trade sectors led to the eventual signing of the trade deal. Although the pandemic has made implementing the deal challenging, trade volumes between China and the US remain massive and both countries are still each other's major trading partners.

Not only that, US investments in China unexpectedly reported a 6% growth (from a year earlier) in the first half of the year when the pandemic was wreaking havoc everywhere. This has a lot to do with phase one trade deal and China's continuous opening up and efforts in improving its foreign investment environment.

Presently, the US has not imposed additional tariffs on China's trade sector. While the trade war has not officially ended, it has not worsened. At the same time, Trump did not fulfil his goal of reducing the US's trade deficit with China through the trade war. On the contrary, the US's trade deficit with China has increased during Trump's term in office. China's exports to the US in August grew a whopping 20% year-on-year. As Trump's first term is ending soon, it is unlikely that the trade war will be a protracted one.*

Amid the US's endless suppression, Huawei has instead overtaken Samsung to become the world's biggest smartphone seller in the second quarter of the year for the first time.

As for the China-US tech war, although issues on Huawei, TikTok, WeChat, and Chinese students and researchers in the US remain controversial, the US has not yet imposed a complete ban on these products and services in the US, and over hundreds of thousands of Chinese students and researchers are still visiting and studying in the US. The US government has repeatedly suspended sanctions against Chinese tech enterprises, and sometimes adopted other means to reduce the impact. A recent example is Trump's last-minute decision to allow TikTok to continue operating in the US. The US government's ban on WeChat was also postponed on the basis that it is "unconstitutional". Academics and scientists have repeatedly emphasised that excessive restrictions and censorship hinder normal research exchanges between both countries and do not align with the US's national interests.

The tech war's impact on Chinese enterprises is limited as well. Amid the US's endless suppression, Huawei has instead overtaken Samsung to become the world's biggest smartphone seller in the second quarter of the year for the first time.

Currently, the biggest variable affecting China-US relations is geopolitics, not economy and trade or technology.

From the analyses above, China's and the US's mutual dependence on each other in the economic and technological fields, limits how far the trade and tech wars can go. Not only do these policies fail to achieve their intended purposes, they are unsustainable, being cut off from globalisation trends and the fundamentals of economic, trade, and technological ties between both countries.

Geopolitics the main threat

Currently, the biggest variable affecting China-US relations is geopolitics, not economy and trade or technology. As the US presidential election nears, people are asking if Democrat Joe Biden would deviate from Trump's tough approach to China. However, of paramount importance is not whether governing styles would change but rather if Biden would continue carrying out acts of suppression against China in the trade and tech fields like Trump, or if he would change his strategy and toughen its stance against China in the geopolitical and security fields instead. If he chooses the latter path, the situation would be much more complicated than the trade and tech wars, and pose a greater challenge to China.

As Trump is a businessman, he did not excessively pressurise China in the military, security, and human rights fields. But Biden is different - as a long-term political heavyweight in the Democratic Party, he is certainly more sensitive to human rights and geopolitical issues. Hence, if Biden is elected, he could gradually ease the trade and tech wars and choose to pressure China in the geopolitical, security, and ideological fields instead.

Editor's Note:

*According to a September report from Deloitte, two-way capital flows between the US and China fell to their lowest level since 2011 in the first six months of 2020. This conclusion is based on two-way foreign direct investment and venture capital investment data from the National Committee on US-China Relations based in New York.

The report says that capital flows were down 16.2% from the same period in 2019 and down roughly 75% from 2016-17. "Specifically, US investment in China fell 31% in the first half of 2020 versus a year earlier. Yet Chinese investment in the US increased 38% - mainly due to a Chinese acquisition of a US-based entertainment company that accounted for 72% of Chinese investment in the US."