Giant Buddha and sponge cities: Combating floods where three rivers meet

The recent floods in Sichuan were serious enough to wet the feet of the Leshan Giant Buddha, which sits on a platform at 362 metres above sea level at the confluence of the Dadu, Qingyi, and Min rivers. Academic Zhang Tiankan explains that while the Giant Buddha represents the ancient Chinese's wisdom in combating floods, modern-day Chinese will need to step up the building of "sponge cities" to prevent floods.

The world-renowned Leshan Giant Buddha is the world's largest sitting Buddha. At 72 metres high, it is 18 metres taller than the Buddhas of Bamyan that previously stood in Afghanistan, before they were blown up by the Taliban on 12 March 2001. In 1996, UNESCO included the Leshan Giant Buddha in its World Heritage List, while it is also a natural cultural landmark of China and Leshan. However, not many know of another key symbolism of the Leshan Giant Buddha: "When the Buddha's feet are washed, Leshan takes a shower."

Washing of the Leshan Buddha's feet

At 6am on 18 August 2020, for the first time ever, the emergency response level was raised to the highest Level I at Leshan city in Sichuan province, at the confluence of the Qingyi, Min, and Dadu rivers. The highlight of the latest flood was the Buddha's feet getting "washed", testimony that the connection between the Buddha's feet and the city's safety is not just a legend or an empty prophecy.

The Leshan Buddha was constructed with the hope of reducing flooding. This was not just idealism but based on science, with cultural and religious symbolism thrown in.

At about 7am on 18 August, the toes of the Leshan Buddha were still above water. But by about 10am, they were submerged. Previously, on 12 August, the platform of the Buddha's feet was covered by the rising water, but the feet were not touched, and the water had receded by the next morning. But on 18 August, it was the first time in 70 years - since 1949 - that the Buddha's toes were submerged. Of course, Leshan city did not disappear, but about a third of it was underwater. Leshan Port, Wang Hao'er Street, Niu'er Bridge, Hei Bridge, Changqing Road, the Feicui/Jade area, Zhongshun Avenue, Baiyang Road, Xiaoba Road were all submerged. Traffic was halted, the areas under overhead bridges were disaster zones, and cars were underwater.

The Leshan Buddha's reputation as a global landmark helped it get its submerged toes on the list of hot searches - the whole world knew about it. However, it seemed that people went from coming together to handle the crisis, to everyone just standing around and watching events as a form of entertainment. Subsequently, 1,020 people were stuck in the Dafoba village on Fengzhou island (also known as Sun island), in Leshan's city centre, but were moved to safety by the next day. But the flood disrupted normal life and work in Leshan city, while the damages would have to be tallied later.

The Leshan Buddha was constructed with the hope of reducing flooding. This was not just idealism but based on science, with cultural and religious symbolism thrown in. In 713 AD, the first year of the Tang dynasty, a well-known monk Haitong had this sitting Buddha constructed in a process that took some 90 years.

The science behind the statue was that constructing a Buddha at the point where the Dadu, Qingyi, and Min rivers converged and struck at the cliffs would reduce the water flow and slow down the river, especially in terms of vessels getting capsized by rapid floods, and the riverbanks overflowing.

Confluence of science and culture in preventing flooding

The science behind the statue was that constructing a Buddha at the point where the Dadu, Qingyi, and Min rivers converged and struck at the cliffs would reduce the water flow and slow down the river, especially in terms of vessels getting capsized by rapid floods, and the riverbanks overflowing. The process also included a certain amount of architectural survey and measurement, such as making sure that the platform for the Buddha's toes stands at the same altitude as Leshan city - 362 metres above sea level.

Part of Leshan city's drainage system passes through the Zhugong tributary into the Min river, after which it joins the Dadu river. If the Min river level is higher than the Zhugong tributary, the water flows backwards, which means that when the water level of the Min river reaches 360 metres above sea level or more, Leshan city will be flooded. Hence the saying: "When the Buddha's feet are washed, Leshan takes a shower." This also means that if the Buddha's feet are soaked, Leshan city has to ramp up drainage, and have somewhere for the water to go, such as building "sponge cities" to absorb large amounts of water. Otherwise there will be flooding.

Of course, cultural and religious symbolism are more universal. With the benign and omnipotent Buddha watching over the three rivers, naturally that would overpower the evil water spirits and beat back the floods, and bless the people along the banks of the three rivers.

It takes effective scientific methods to handle this backwater effect, one of which is building sponge cities

For over 1,000 years, the scientific and cultural basis of constructing the Buddha has indeed protected the people at the confluence of the three rivers. But today, there are even stricter scientific requirements against floods. It is not just this year that the Leshan Buddha had its feet washed. It has happened many times before, and it has once again been made clear that there has to be rational and effective science against flooding, including integrating local climatic and geographical features.

Building 'sponge cities' to tackle backwater effect

Leshan's unique geography is that it lies at the confluence of the three rivers, which will all rise during heavy rains and the wet seasons. The waters then converge in the Leshan area and create a backwater effect, where water flow is obstructed by the high water level of the main river, creating poor drainage. This happens in many cities - when major rivers bring high water volume, it affects local water flow and drainage, and creates flooding in cities that worsens crises and hinders rescue efforts.

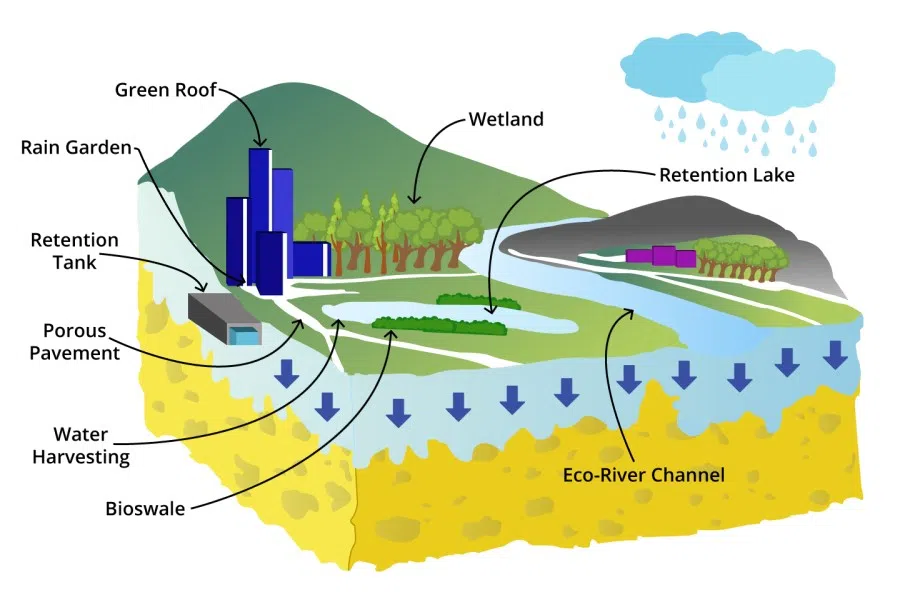

It takes effective scientific methods to handle this backwater effect, one of which is building sponge cities, which means building low-impact development rainwater systems in cities, including rivers, lakes, ponds, and wetlands, as well as urban infrastructure like green spaces, green roofs, gardens, and permeable roads. When it rains, these features absorb, store, drain, and purify water, and also allows most of this rainwater to be released and used locally when necessary, while the excess is drained through pipes and pump stations, so that the rainwater is freely moved in the cities and reduces the pressure of flooding.

Sponge cities are universally applicable, not just in Leshan, but for other cities in China. In 2015, China's State Council released "Document 75: Guidelines for Building Sponge Cities" to collect and utilise 70% of rainwater, with 20% of urban areas meeting the target by 2020, and 80% by 2030. If this target is met, even a major flood would not submerge the cities, or just slightly, and drainage would also be rapid.

In May 2018, the Leshan people's government released a paper on ecological and urban recovery for the city. It proposed increased protection of the natural environment of Mount Emei and the Leshan Buddha, and integrated management of the lakes, wetlands, and rivers, particularly the Leshan stretch of the Qingyi river. It was a strong push for sponge cities, with the rivers, reservoirs, wetlands, drainage, green spaces, and forests in the city centre brought into an integrated plan where sponge city infrastructure would cover at least 25% of the built-up urban area by 2020.

This plan is more avant-garde than Document 75. But the latest flood still submerged Leshan city, showing that building sponge cities can be pushed forward much further and much faster. Of course, this is not just happening in Leshan. Wuzhou in Guangxi is also situated at the confluence of three rivers (the Gui, Xun, and Xi rivers), and in February 2018, it also released a blueprint for building a sponge city. But the torrential rain and flood of 6 to 8 June this year submerged Wuzhou's old port, while roads and houses in Changwu county were underwater, and some roads even collapsed.

Wuhan was flooded practically every year since 2011, but after learning from experience, it started building a sponge city in 2015.

This shows that in places like Leshan and Wuzhou, where three rivers meet, it is very difficult to build a sponge city; it takes experience and hard work. In fact, many cities have been successful in building sponge cities against floods. For instance, Wuhan was flooded practically every year since 2011, but after learning from experience, it started building a sponge city in 2015. On 4 to 5 July 2020, Wuhan saw seven rounds of heavy downpour due to the rainy season, with the highest single-day rainfall in history of 426.6 millimetres. But there was no need for "river-watching" in Wuhan, because the sponge city project yielded early results. Even with the torrential rains on 5 and 6 July, the worst buildup of water receded within six hours. And on 7 July, Wuhan's gaokao examination centres remained operational amid the torrent.

There are many ways to fight floods, and sponge cities are just one way. Cities like Leshan and Wuzhou are classic examples of using geography to build sponge cities while also using other effective methods and techniques to prevent flooding, such as early warnings. Hopefully this is the last time the Leshan Buddha will have its feet washed. Indeed, it should remain as history, legend, and light-hearted humour.

Fortunately, by 8:30am on 19 August, the water level of the three rivers had receded below the level of the platform for the Buddha's feet, while the water level at Fengzhou island across the river also fell. The giant Buddha and Leshan were once again safe, but more work needs to be done against flooding, which includes preparing for it before it even happens.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)