Governing Hong Kong: Beijing needs to tread carefully with the national security law

What does Moisés Naím's 2013 book tell us about power in the modern world and how is this related to the recent high-profile arrests of Hong Kong media tycoon Jimmy Lai and former member of the Standing Committee of Demosistō Agnes Chow under the Hong Kong national security law? Can China's style of showing power maintain peace in society? How long would its deterrence work in Hong Kong society?

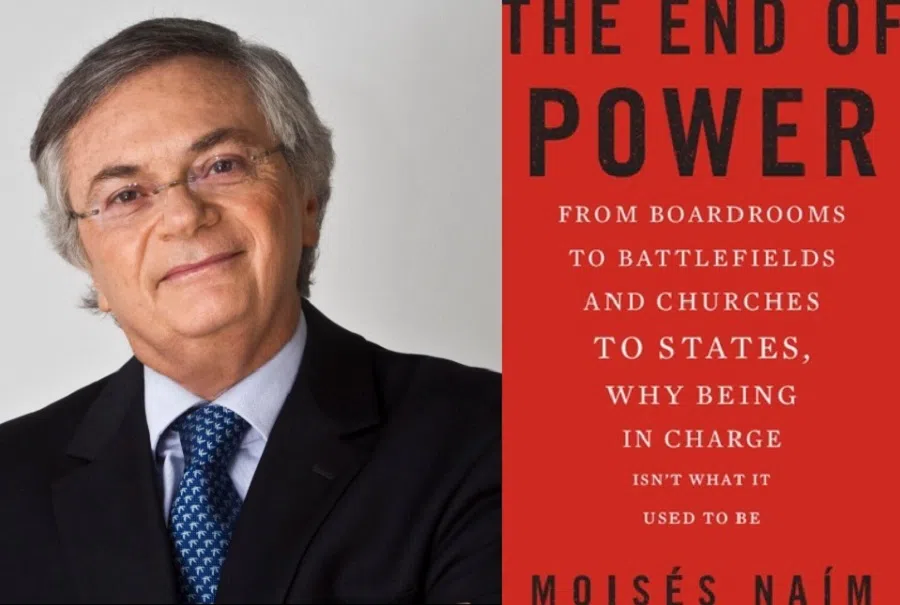

International political commentator and former Venezuelan Minister of Trade and Industry Moisés Naím pointed out in his 2013 book The End of Power: From Boardrooms to Battlefields and Churches to States, Why Being In Charge Isn't What It Used to Be a fundamental change that most people were still unaware of - in the modern world, "power is decaying". Generally speaking, "power is easier to get, harder to use and easier to lose". In other words, power is depreciating. This phenomenon is observed across the different aspects of a country, including its domestic politics, commerce, religion, science, and education.

As a good storyteller, Naím used the true story of a young competitive chess player as an opener to his book, vividly explaining how power is decaying. In 2011, a 12-year-old African American boy became a Master at chess. This is an outstanding achievement, but it is no longer exceptional as an increasing number of chess players are achieving mastery at much younger ages, a trend contributed by the digital revolution, an open world, and higher education standards.

In 1972, there were only 88 Grandmasters at chess, the highest title a chess player can attain. By 2013, this number grew to 1,200. Furthermore, once a new champion is hailed, the achievements of the masters are quickly surpassed.

On the morning of 10 August, the Hong Kong police made high-profile arrests of ten people, including Next Digital founder Jimmy Lai, and former member of the Standing Committee of Demosistō Agnes Chow. Upon hearing this news, I am once again reminded of Naím's The End of Power.

This move is also believed to have the biggest psychological impact to Hong Kongers since the implementation of the national security law.

Over the past year, Lai has been the target of harsh criticisms by mainland Chinese media, which have dubbed him the "ring leader" of Hong Kong's new "Gang of Four". Thus, his arrest under the Hong Kong national security law is unsurprising. The Chinese central government had carefully planned and meticulously designed the airtight Hong Kong national security law with the intention of arresting people whom they considered pro-democracy activists, especially high-profile advocates of international sanctions against Hong Kong, on a legal basis and with reason on their side.

However, Lai's arrest, as well as the Hong Kong police's arrest of ten people at one go, still produced a strong deterrent effect nonetheless. This move is also believed to have the biggest psychological impact to Hong Kongers since the implementation of the national security law.

These actions showed the people a familiar mainland Chinese modus operandi: first, establish a legislation and set the rules. Then, make high-profile arrests of "ring leaders" of the crime to create a strong deterrent effect.

The entire process created a series of dramatic scenes: Lai was first arrested at his home and then escorted to Next Digital headquarters near noon where a raid occurred. Apple Daily live streamed the process, which showed Lai walking through the Apple Daily newsroom in handcuffs. That same day, over 200 police officers also searched Next Digital headquarters for four hours. That night, Chow was handcuffed and driven away in a police car from her apartment. The next morning, Lai was again escorted to the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club Shelter Cove Clubhouse in Sai Kung for evidence collection. These actions showed the people a familiar mainland Chinese modus operandi: first, establish a legislation and set the rules. Then, make high-profile arrests of "ring leaders" of the crime to create a strong deterrent effect.

If this had happened last year without the national security law in place, protesters would have immediately taken to the streets. But this week, there were only scattered protests; Hong Kongers have been restrained in airing their objections on social media. In this sense, the national security law has worked wonders - the "protest army" numbering in the hundreds of thousands has been dispersed, leaving Hong Kongers to feel the power of deterrence. Some Hong Kongers hoped that pressure from the international community would soften Beijing, but this proved futile.

But when applied to a modern society like Hong Kong, with its tradition of "Chinese political refugees", free flow of information, and a strong individualistic streak, can China's style of displaying power maintain peace in society?

But Hong Kongers are still subtly expressing resistance, such as buying up all 550,000 copies of Apple Daily (including an additional print run), and individual shareholders pushing up Next Digital share prices to five times their original price (of course this would include some opportunists looking to profit). People even queued to patronise the eateries run by Jimmy Lai, clearly reflecting the undercurrents in society. Hong Kongers sticking by Apple Daily may not stem out of support for Lai himself; fundamentally it is a venting of their unhappiness at the national security law and their worries about the future of "one country, two systems". As long as this consciousness remains strong, there will always be an avenue of resistance.

Naím foresaw that the days of traditional power having strong sustained dominance are long gone, and this trend is even clearer in a global sense. Of course, mainland China remains a rare case of a political entity with highly centralised power, where Western systems at times pale beside its administrative efficiency.

But when applied to a modern society like Hong Kong, with its tradition of "Chinese political refugees", free flow of information, and a strong individualistic streak, can China's style of displaying power maintain peace in society? The outlook does not seem too encouraging.

It also needs a change in mindset about governance; deterrence may work for a while, but people will find avenues of resistance. After all, Hong Kong is not mainland China.

Some people say that arresting the group of ten including Lai, and the high-profile search into the media may be "overkill". Indeed, the authorities should not make this a norm. If there is strong backlash from Hong Kongers and mainland China is forced to step in or even use force, that would definitely be a lose-lose result. This week, the National People's Congress extended Hong Kong's Legislative Council term, and the four pan-Democratic members who were declared ineligible for the next elections are expected to keep their seats for another year, which is a friendly overture by Beijing to the pan-Democratic camp, a rare signal of peace.

By that logic, with the national security law as a buttress, apart from necessary measures according to the law, the authorities have to be extremely careful in its show of power as a deterrent in Hong Kong. It also needs a change in mindset about governance; deterrence may work for a while, but people will find avenues of resistance. After all, Hong Kong is not mainland China.