Grandson of HK shipping tycoon returns to steer Wah Kwong into new era

Hing Chao, the grandson of one of Hong Kong's four shipping tycoons, Chao Tsong-Yea, is the current executive chairman of Wah Kwong Maritime Transport. He was previously focused on preserving culture and promoting martial arts, and did not have much corporate management experience. Even so, since taking over, Wah Kwong's new asset management business grew rapidly within a few years. Today, the company manages more than 80 ships, a manifold increase from the 20 or so vessels under its management before the pandemic. The company is also looking into setting up an office in Singapore. Zaobao senior correspondent Chew Boon Leong speaks to him to find out what inspired him to take on the family business.

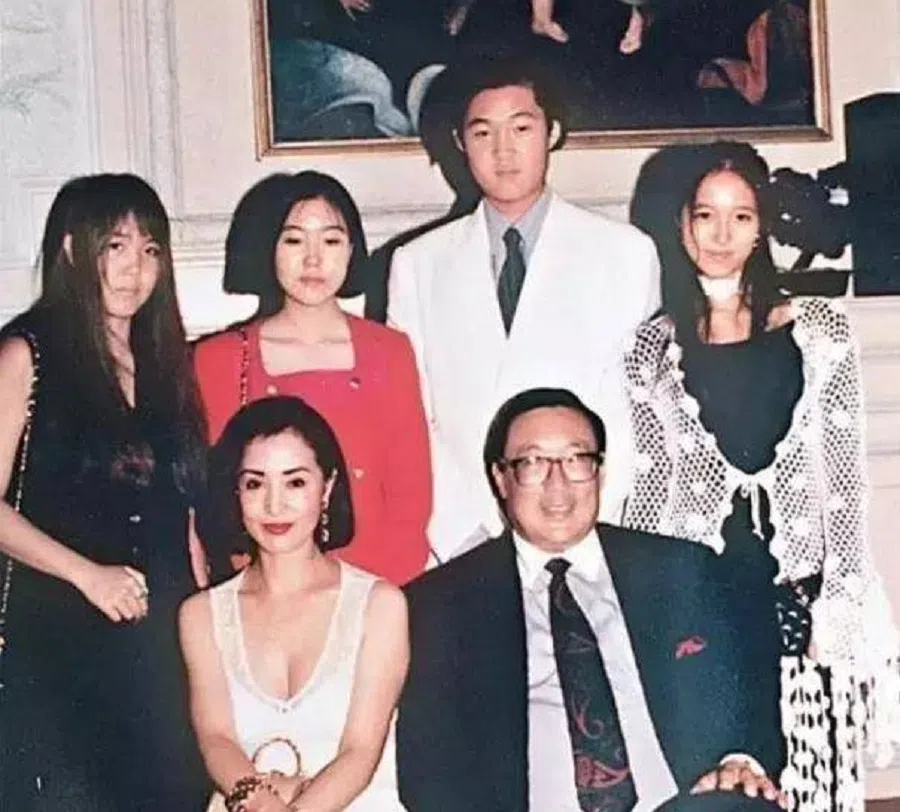

Hing Chao is the son of Lily Ho, a Shaw Brothers movie star of the 1970s. As a child, he learned the cello, which sowed in him the seeds of the arts. In 2015, he started the Hong Kong Culture Festival, showcasing the charms of Hong Kong's traditional arts and festivals through various artistic formats.

Chao is also passionate about the preservation of intangible cultural heritage, particularly the Orochen culture of Inner Mongolia; he is the chairman of the Hong Kong Orochen Foundation.

He also likes martial arts, and has learned karate, nanquan (南拳) and hung kuen (洪拳), among others. He actively promotes wushu or Chinese martial arts - he established the International Guoshu Association (中华国术总会) and published a book Hung Kuen Fundamentals: Gung Gee Fok Fu Kuen (《洪拳入门:伏虎拳》).

But while Chao wears many hats - arts planner, cultural heritage preserver, martial artist - he is best known as the grandson of Chao Tsong-Yea, one of Hong Kong's four shipping tycoons, and as the current executive chairman of Wah Kwong Maritime Transport.

Founded by Chao Tsong-Yea in 1952, Wah Kwong is an established shipping company in Hong Kong that runs a diverse fleet, while also offering technical management for vessels including bulk carriers, crude oil tankers and LPG carriers.

Hit the ground running

In 2019, Chao took over the reins of Wah Kwong from his elder sister, Sabrina Chao. Despite not having any prior experience in managing a large company, he quickly showed outstanding business acumen. In a few short years, he quickly and successfully opened up Wah Kwong's asset-light operations such as shipbuilding supervision, ship management and commercial management.

The company's fleet expanded from 25 to 30 vessels before the pandemic to 80 to 90 today. In the last few years, it has also expanded operations by setting up offices in Shenzhen and London in 2020 and 2022, and will next start establishing an office in Italy.

In an interview with Lianhe Zaobao when he was in Singapore for the Forbes Global CEO Conference, Chao revealed that his company was also looking into setting up an office here.

He said, "We registered a company in Singapore many years ago, but do not have an office here yet. Singapore is an important shipping hub in Asia, so as Wah Kwong expands and diversifies, having an office here will provide operational benefits."

During the pandemic, Chao boldly revamped Wah Kwong's business model, moving away from just traditional ship-owning to two areas - asset heavy ship-owning, and asset-light asset management - while deepening cooperation with its partners.

At 1.9 metres tall, the 45-year-old stands out from any crowd and makes for an imposing figure. His hard, unsmiling appearance projects a feeling of unapproachability and coldness. But after interacting with him, I found that below his serious exterior lies a passionate heart.

His eyes light up when we talk about martial arts and Orochen culture, and his words carry the idealism of the educated. Speaking of the impact of the passing of his father George Chao, he said he was a rebellious young man who often opposed his father - his even tone could not hide the traces of guilt and remorse.

Chao graduated from Durham University, where he read philosophy and history. In running Wah Kwong, he takes a different approach from most business people, as he looks at the development of the shipping market from a broader historical perspective.

Chao notes that the global shipping market is constantly changing, from low market demand in the early phase of the pandemic, to a spike in demand and prices; and now, with gradual recovery, the shipping industry faces overcapacity and empty shipping containers.

"However, if we look at this as part of an industry cycle, the shipping industry is still about supply and demand. Today, the world is at a crossroads, and we may witness the beginning of a new global political and economic order. While there are many disruptive factors, there are also plenty of opportunities."

Bold revamps

During the pandemic, Chao boldly revamped Wah Kwong's business model, moving away from just traditional ship-owning to two areas - asset heavy ship-owning, and asset-light asset management - while deepening cooperation with its partners.

Chao felt that a good shipping company had to be able to thrive amid change: it should be adaptable, flexible and unafraid of making big decisions.

Chao explained that the quarantine and travel restrictions during the pandemic made it hard to operate, and he realised that the company needed to diversify and become nimbler. Also, the impact of disruptive factors like decarbonising and digitalisation means that ship owners, lessees and manufacturers need to work more closely.

For a shipping company with more than 70 years of history, sudden transformation was not easy. However, Chao felt that a good shipping company had to be able to thrive amid change: it should be adaptable, flexible and unafraid of making big decisions.

In 1973, Wah Kwong was publicly listed in Hong Kong, but faced a financial crisis in the 1980s due to a downturn in the shipping industry. Chao Tsong-Yea had to resort to selling assets to repay the company's HK$6.7 billion debt. In 2000, Wah Kwong was privatised; in 2008, the company's plan for a new public listing was shelved due to lukewarm interest.

"Because I had no baggage, I could be bold and think further. I was also willing to be ahead of the times." - Hing Chao, executive chairman of Wah Kwong Maritime Transport

Chao said that Wah Kwong's journey in the last 70 years has not been smooth sailing, as it has gone through wind and rain, highs and lows. "These challenges have made Wah Kwong more resilient, so that we can pick ourselves up wherever we fall."

As a history and humanities buff, Chao is not afraid to say that he is something of an idealist in heading Wah Kwong. "But in this commercialised world, we do need such idealism and a more inspiring corporate vision."

He added that he was previously busy with preserving culture and promoting martial arts and did not build up corporate management knowledge and experience - this might have been the edge in his leading Wah Kwong's transformation.

"Because I had no baggage, I could be bold and think further. I was also willing to be ahead of the times."

A humanities and martial arts buff

Even though Chao was born with a silver spoon in his mouth, he has his own interesting take on life, prompting him to take a relatively unique and challenging route to taking over his family business.

As the grandson of a shipping magnate and his father's only son, from a young age his parents and elders put high hopes on him and saw him as the only choice to inherit the family business.

But perhaps due to youthful rebelliousness or a preference for the humanities, Chao's dream in his younger days was not to take over the family business, but to promote traditional culture and martial arts. His father asked him several times to help out with the business, but he never felt up to it; over time, this led to a sense of aversion and thoughts of escape.

"Inner Mongolia was a difficult phase in my life, but I learnt a lot from the experience, like how the locals continue to lead simple and happy lives in a difficult environment, and how to cope with change and to innovate when there is no way out." - Hing Chao

On his relationship with his father, Chao said, "When I was young, my father was a formidable figure. I always felt like he could handle anything, and there was no need for me to worry about the family business. So, when I was younger, I did not think much about taking over Wah Kwong, but just kept doing what I wanted to."

When he was 13, Chao's parents sent him to study in the UK. He was initially uninterested in literature and history, but somehow ended up liking the humanities. In his fourth year of university, ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, art, and tragedies were his daily companions - his mind was filled with Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, which gradually formed the idealism of a literati.

Chao's interests grew to include the Hakka Qilin dance, Taoist music, Nanyin music, and puppet shows. To him, all these are Hong Kong's unique cultural assets.

Turning point: Inner Mongolia

After graduating, Chao went to Inner Mongolia in 2001, where he lived for a month, just to experience life. That month of wandering completely changed his outlook on life, and was the biggest turning point of his life.

At the time, Inner Mongolia lacked resources, with frequent water and power outages at the hotel. Even worse, the internet was not advanced and he could not withdraw cash from the small-town bank. When Chao found he spent every cent of his money, he had no choice but to move in with the locals.

Just when he had nothing and needed to rely on others, Chao learnt an important life lesson - how rich a person is does not lie in his wealth or status, but in how much they are willing to give to others.

He said, "Inner Mongolia was a difficult phase in my life, but I learnt a lot from the experience, like how the locals continue to lead simple and happy lives in a difficult environment, and how to cope with change and to innovate when there is no way out."

He said that even in the poorest villages, the locals were unafraid and still unselfishly helped others. Most people in Inner Mongolia did not treat him differently because of who he was. They saw him as an ordinary person - everyone ate and lived together, kept warm, and got through the cold and heat.

Eventually, Inner Mongolia became Chao's spiritual utopia, a place where he could let down his guard and interact frankly with others. Gradually, he fell in love with the place.

Chao compiled the photographs he took in Inner Mongolia and held a photo exhibition. With the help of family and friends, he set up the Hong Kong Orochen Foundation in 2004, starting his work to preserve Inner Mongolian culture. Every year, he goes back for three to four months to conduct field studies and oral history interviews; he has also published books and produced documentaries.

Starting with the intangible cultural heritage of Inner Mongolia, Chao's interests grew to include the Hakka Qilin dance, Taoist music, Nanyin music, and puppet shows. To him, all these are Hong Kong's unique cultural assets.

In 2015, Chao organised the inaugural Hong Kong Culture Festival, focusing on promoting intangible cultural heritage. He thought the festival would only be held once or twice - he never thought it would still be running now, after nine editions.

Hopes of modernising wushu

Chao has also practised martial arts since young. For nearly 20 years, he followed Chan Chuek Sam (陈卓森) in learning karate; later, he also learned from Ma Mingda, an exponent of northern China martial arts, and Lam Chun Fai, the grandmaster of Lam Ka Hung Kuen.

Chao said martial arts has been a huge influence in his life. In his youth, martial arts was a form of physical training, but now, he practises to slow down and experience life at a slower pace.

In recent years, he has also been actively promoting wushu, including establishing the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area Wushu Alliance with fellow wushu enthusiasts last year.

Chao said that while wushu has a rich history, today its position is increasingly unclear, and so he hopes to modernise it and implement systematic reforms so that like karate and taekwondo, it can also be a combat sport with a comprehensive method and value system.

"Perhaps I was averse to running the family business before, which led to conflicts from time to time, but generally I'm still enjoying the process." - Hing Chao

Father's death was a blow and driving force

In the decade or so that Chao was busy with cultural preservation, Wah Kwong saw many major twists and turns. From a publicly listed company, it was privatised before plans for a subsequent public listing were shelved owing to lukewarm interest.

Meanwhile, following the passing of Chao Tsong-Yea and Frank Chao, and George Chao suffering a stroke in 2004, the onus of running Wah Kwong fell on Chao's elder sister, Sabrina. In 2013, after the long-term hospitalisation of the ailing George Chao, Sabrina Chao became Wah Kwong's executive chairman, in charge of all operations.

Seeing his father bedridden for years and his sister having to run the family business on her own while he took no part, on the one hand, Chao was guilt-stricken, feeling irresponsible and unfilial.

On the other hand, he also felt that his interests did not lie in business. He did put in effort to try, but failed as he did not know how to do anything; there was a youthful rebelliousness and anger, of "why don't you understand me?"

In 2016, George Chao passed away at the age of 76.

On his father's passing, Chao said, "His death was a big blow for me. At the same time, it was a huge impetus behind my decision to return to Wah Kwong."

At this point, he paused in thought before continuing, "My father once told me that my chosen course in the humanities may not be related to my career. He always trusted me and believed that I would find my way back eventually."

In life, sometimes we have to go in a circle before coming back to where we started, in order to find inner peace.

In 2017, Chao returned to Wah Kwong.

By then, he was more mature, and with his elder sister mentoring him in how to run the business, he quickly got the hang of Wah Kwong's operations. In 2019, Chao became Wah Kwong's executive chairman and officially took over its reins.

Chao said, "My taking over of Wah Kwong was part of a long-term succession plan, and the adjustments to the company these few years are the result of many discussions with my elder sister. Perhaps I was averse to running the family business before, which led to conflicts from time to time, but generally I'm still enjoying the process."

Finding his place in life

Although he spends most of his time running Wah Kwong now, Chao still sets aside some time for the work he likes: preserving culture and promoting wushu.

When I asked whether he would lead a more carefree life without struggling between cultural work and the family business if he were not born into a shipping family, Chao did not hesitate. "No. It is precisely my strong family backing which has enabled me to do more. I am very happy, because what I do is meaningful."

He said he can now easily navigate his various identities as a shipping tycoon's grandson, businessman, preserver of culture, and promoter of wushu; he has found his place in life, and a comfortable pace of living.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "远航终不忘归途 船王之孙掌舵破前浪".

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)