[Photo story] 103-year-old Flying Tiger returns to the skies

Photo collector Zou Dehuai shares his treasured collection of photos showing the life of the late Ho Weng Toh, who was until a while ago the last of the Asian Flying Tigers and a founding pilot with Singapore Airlines. As a hero that could not sit back and watch his motherland in pain, Ho’s story is one of determination and bravery.

(All photos courtesy of Zou Dehuai.)

Just six months before passing, Ho Weng Toh managed to spot his younger self in an old photograph from my collection.

On the morning of 6 January this year, he passed away at the age of 103. Ho was the last of the Asian Flying Tigers and a founding pilot with Singapore Airlines.

After having raised enough funds on his own, independent documentary filmmaker Lai Endian flew to Singapore in June 2023 to interview Ho for an oral history documentary. Before his trip, Lai asked for my help with his preparation.

Old photos and memorabilia

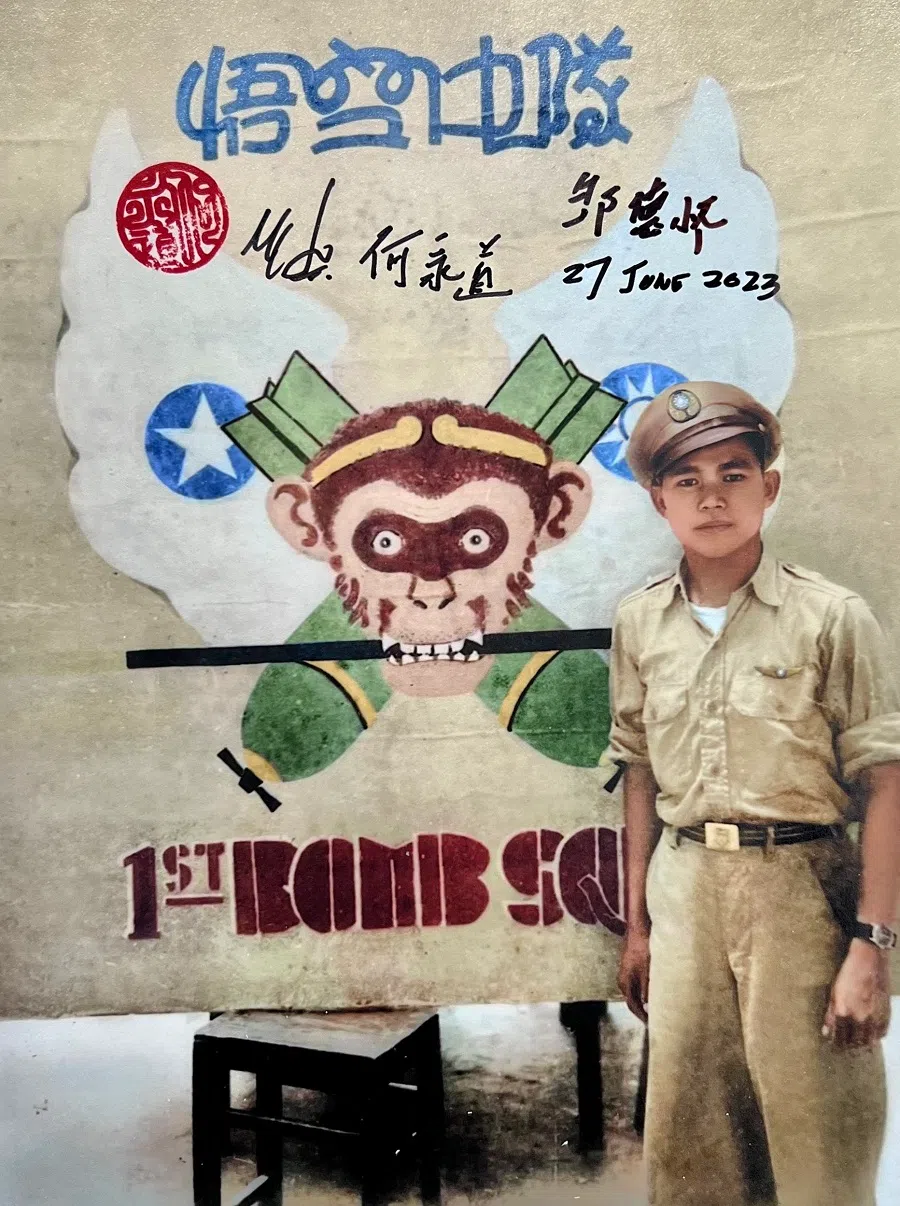

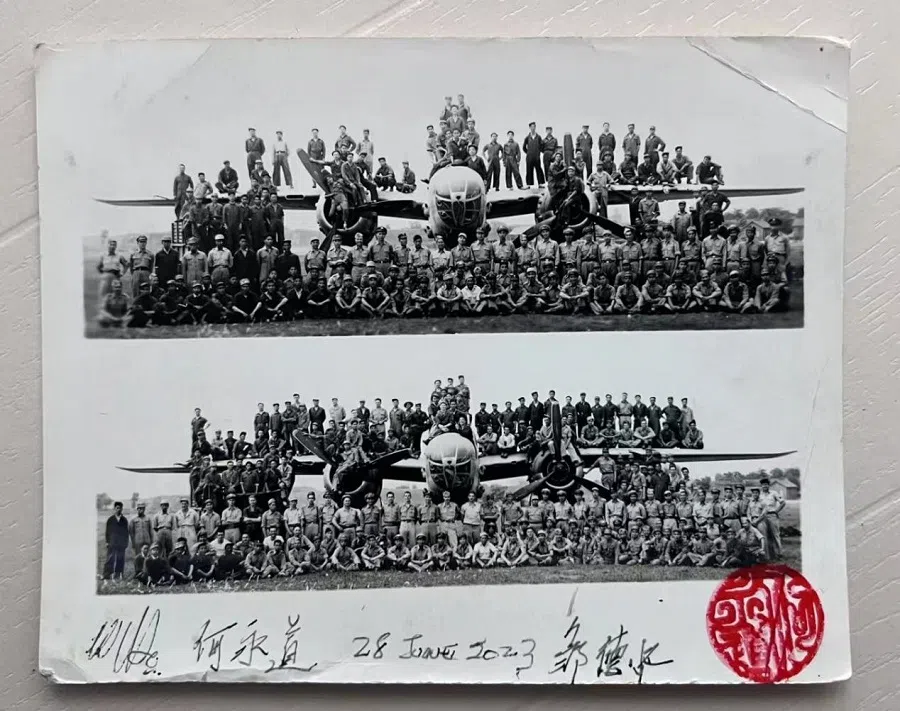

I excitedly searched high and low, day and night before finding an old group photo of the First Group of the Chinese-American Composite Wing (CACW) taken in 1945 in Hanzhong, Shaanxi. I scanned the photograph in high resolution and reprinted an enlarged copy. I also developed another colourised photo that showed Ho posing with his group emblem during the Second World War.

I mailed these originals and replicas in a package over to Lai. I hoped that Ho would be able to spot his younger self in the group photo and, if possible, leave his signature on the photo as a souvenir to make it one of my treasured collections.

Thankfully, Lai’s filming work went off without a hitch. At 103 years of age, Ho’s senses were still sharp. He loved the two photographs I prepared and even managed to find his younger self in the group photo with the help of a magnifying glass.

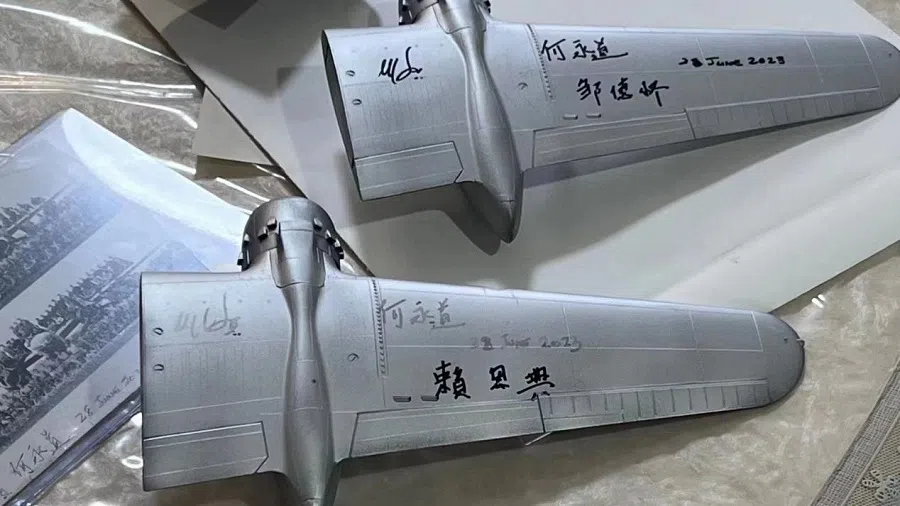

After the completion of the shoot on 27 June, the centenarian cheerfully signed his name on the photos. To my pleasant surprise, he even wrote the Chinese characters of my name “邹德怀” on them, and this moved me to tears. After learning about the challenges that Lai faced in raising funds for his documentary, Ho agreed to sign on all the 24 photos developed and the ten B-25 Mitchell bomber plane models, and gave permission for Lai to sell these items to fund his film.

Ho asked Lai, “What’s the point of your filming? Even today, the Japanese refuse to reflect on what they did, they did not even issue an apology.”

For us, the most meaningful part of recording all these is for future generations to remember the numerous national heroes who braved their lives during the war.

Born in 1920 in Ipoh, Malaysia, Ho’s ancestral home was in Shunde, Foshan. His father is He Guolian, a prominent figure in the local community and the general manager of the Shunde Association in Ipoh. At that time, Malaysia was a British colony and the Chinese there were treated as second-class citizens who often suffered unfair treatment.

Ho was bright and ambitious. Even though he was born and raised abroad, he longed for his distant motherland. When it was time for him to attend university, he resolutely decided to return to China for further studies.

“I was not the least concerned when enemy fire skimmed my plane. There was no worry or fear, and I was not afraid to die because I was completely filled with the satisfaction of being able to confront the invaders head on. I was like a completely different person and totally fearless.” — the late Ho Weng Toh

Defending his motherland

When war broke out between China and Japan, he was studying engineering at University of Hong Kong and later at Sun Yat-sen University. The local schools were forced to close after Japan advanced southwards and occupied Hong Kong.

In his 70s, Ho had the following recollection and said, “I witnessed the first day the Japanese occupied Hong Kong. The Japanese planes bombed Kai Tak airport. When I went in, it was announced that the World War had begun.”

Having witnessed Japanese atrocities day and night, Ho refused to lay down and submit.

In 1942, after being provided with funds by Chinese entrepreneur Aw Boon Haw, Ho decided to do his part. Ho slipped into the mainland and made it to Guilin after much trouble and hardship.

At the time, Japanese troops were laying waste to China with their unrestrained bombings. Countless innocent Chinese perished in the flames of war. Ho was filled with sadness and anger in the face of such shocking scenes. When he came across a Republic of China Air Force recruitment poster, he duly signed up to defend his motherland.

Ho was determined to enrol in air force school.

After passing the entrance exams, Ho was selected to join the Flying Tigers, a collaboration between China and the US. He completed different phases of his training in Kunming, Lahore in India, and Phoenix in the US, before qualifying as a bomber pilot.

In September 1944, Ho returned to Chongqing to join the first squadron of the CACW First Group and was based in Hanzhong, Shaanxi.

Ho participated in the Central Plains War and then in the Burma campaign.

He flew the B-25 Mitchell bomber and fearlessly completed 18 bombing missions against the invaders of China, destroying Japanese military bases, ammunition depots, train depots, and other facilities.

On his close encounters with the Japanese troops, Ho recounted, “I was not the least concerned when enemy fire skimmed my plane. There was no worry or fear, and I was not afraid to die because I was completely filled with the satisfaction of being able to confront the invaders head on. I was like a completely different person and totally fearless.”

He [Ho] and his family became Singapore citizens during the years of the Lim Yew Hock administration. On this, he delightfully said, “I have a brand-new identity and am no longer a second-class citizen, now I feel an ease and tranquillity that I have never experienced before.”

Becoming a pioneer in Singapore

Ho was well regarded by his superiors for his air prowess and was promoted to lieutenant.

After the Second World War, he transported goods to various parts of China to aid rebuilding efforts. He later became a commercial pilot of the Central Air Transport Corporation in Shanghai.

Amid the turbulence of 1949, Ho could not bear to see his countrymen engage in an internal war and returned to Nanyang with his family. He and his family became Singapore citizens during the years of the Lim Yew Hock administration. On this, he delightfully said, “I have a brand-new identity and am no longer a second-class citizen, now I feel an ease and tranquillity that I have never experienced before.”

In 1953, Ho joined Malayan Airways, the predecessor of Singapore Airlines, as its first batch of Chinese pilots. During his career with the airlines, he trained more than 300 pilots and accumulated over 20,000 hours of flight time. He served 29 years in the company before retiring in 1980.

“Old soldiers never die”, they live on in our memory.