In Indonesia, Chinese financing for coal-fired power plants grows faster than that for renewables

In 2020, Chinese firms invested a total of US$4.8 billion in Indonesia, ranking second only to Singaporean firms (US$9.8 billion). Corporate China's stellar showing is unsurprising, given how proactive Indonesian policymakers have been in courting Chinese investors.

This stance is exemplified by President Joko 'Jokowi' Widodo (2014 to present), who came to power promising to uplift Indonesia's creaking infrastructure. Interestingly, this massive infrastructure drive is also accompanied by a vow to reduce Indonesia's carbon footprint.

To this end, Jokowi has committed to derive 23% of Indonesian primary energy needs from renewable sources - defined as geothermal, wind, bioenergy, solar, hydropower, and hydrokinetic ocean and ocean thermal energies - by 2025.

Notwithstanding the broad narrative and seeming optimism, how has greater involvement of Chinese firms promoted renewable energy adoption? Our recent analysis is less than sanguine.

Chinese financing poured into non-renewable energy infrastructure

It is undeniable that substantial Chinese money has been channelled to finance energy infrastructure across the archipelago, especially in places that were less interesting for foreign investors in the past. As development in Indonesia has been Java-centric for decades, capital and technology introduced by Chinese firms have significantly improved energy access of communities in the outer islands.

Renewable energy development, in particular, has received the shot in the arm that it so badly needs. Some of the more prominent examples include solar and wind energy farms in South Sumatra and South Sulawesi respectively. For this, Indonesian policymakers deserve credit. Relatedly, it is plausible that the rollout of such projects has contributed to Jokowi's successful presidential reelection of mid-2019.

... as much as 86% of Chinese financing, provided primarily by China Development Bank (CDB) and China Export-Import Bank (CHEXIM), has been channelled towards coal-fired power plants.

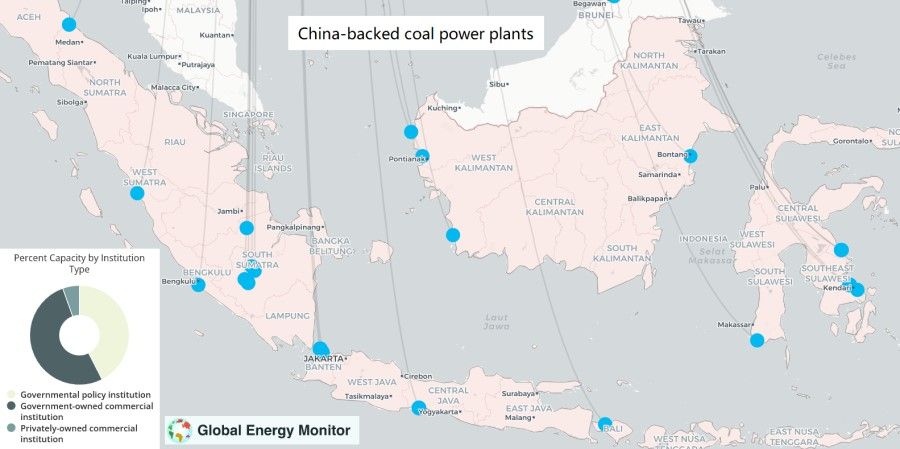

However, perhaps more worryingly, financing for non-renewable energy infrastructure has grown faster than that for renewables. The dataset in our study shows that as much as 86% of Chinese financing, provided primarily by China Development Bank (CDB) and China Export-Import Bank (CHEXIM), has been channelled towards coal-fired power plants.

In addition to complicating Indonesia's objective of deriving at least 23% of its primary energy needs from renewable sources, the proliferation of coal-fired power plants has almost certainly harmed the Southeast Asian nation's climate commitment.

The state-business alliance

Moreover, observers have grown increasingly jittery about Indonesia's debt levels amidst its infrastructure push. Although Jokowi has experimented with public-private partnerships to lighten the financial stress, one cannot avoid the observation that government debt has expanded noticeably since he entered office.

Indeed, shortly before the 2019 presidential election, the Jokowi administration raked up debt amounting to about US$181 billion. This represented a 48% increase from the US$122 billion it had inherited from the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono administration (2004-2014). By April 2022, Indonesia's government debt has climbed up to US$190.5 billion. While such debt is not owed exclusively to Chinese lenders, the reality is that it still represents a substantial increase from that left behind by the former administration.

A cynic could thus claim that the proliferation of these coal-fired power plants has created an opening for the Indonesian coal players to establish ties with their Chinese counterparts, securing a captive market for their coal supplies.

Questions have also been raised about the state-business alliance forged amidst the robust expansion of coal-fired power plants.

The typical arrangement sees loans provided by CDB and CHEXIM, with Chinese firms offering technical expertise in the form of engineering, procurement and construction contractors. This is de facto a turnkey arrangement, meaning that local firms do not get to participate directly in the engineering process.

Yet, Indonesian enterprises enjoy leeway in other indirect activities such as the provision of coal and related logistical services. A cynic could thus claim that the proliferation of these coal-fired power plants has created an opening for the Indonesian coal players to establish ties with their Chinese counterparts, securing a captive market for their coal supplies.

More critically, the Indonesian mining industry - of which coal is a core component - has been alleged to finance the political campaigns of prominent politicians in the country's 2019 general election.

A robust governance mechanism is thus needed to effectively plug these loopholes of China's "no coal" policies.

Plug loopholes in China's 'no coal' policies

What do we make of these findings then? For one, coal-fired power plants will likely remain important, at least in the near to medium term.

Although the Chinese government has pledged in late 2021 to stop building new coal-fired power plants abroad, commercial-cum-legal loopholes remain for opportunistic parties to push certain projects. Additionally, committed projects and those coming online will continue to emit large quantities of greenhouse gas, heating up the planet. They will also take decades to retire and mothball.

A robust governance mechanism is thus needed to effectively plug these loopholes of China's "no coal" policies. Potentially, the Chinese government could introduce regulations to better monitor the environmental performance of its energy firms venturing abroad. As an increasingly influential player on the global stage, it is only right that the Chinese take more concrete steps to phase coal out more meaningfully.

On the Indonesian side, it is equally important that environmentally-conscious stakeholders pressure the Indonesian government and business groups more effectively, as well as their financiers, in releasing timely information to the public.

Enhanced transparency is expected to foster a greater understanding of how international (including Chinese) capital is embedded into the national and local ecosystems. A more informed view of these issues and their interplay can then help policymakers and analysts formulate more effective policies to not only limit the growth of non-renewable energy infrastructure, but also redirect much-needed resources to promote renewable ones.

This article is based on the findings of a recent research paper, titled 'China-Japan Rivalry and Southeast Asian Renewable Energy Development: Who Is Winning What in Indonesia?', published in Asian Perspective.

Related: China's push towards green energy accelerated by security concerns | Why China's once red-hot solar sector is cooling | Net-zero CO2 emissions before 2060: Is China's climate goal too ambitious? | US-China competition in climate cooperation a good thing for Southeast Asia | China and US could work on building clean and green BRI and Build Back Better World (B3W)