Memories of South China: The enchanting garden that Whampoa built in Singapore

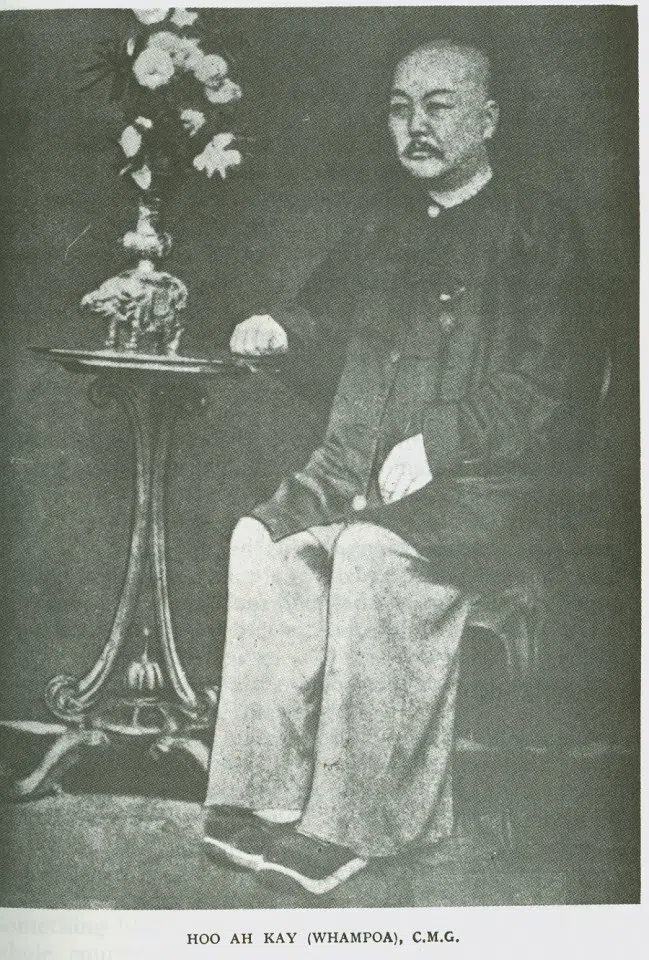

It is commonly thought that Singapore's horticultural history dates back to the beginnings of the Singapore Botanic Gardens. Actually, a little earlier in the mid-19th century, Singapore pioneer Hoo Ah Kay, known as "Whampoa" after his hometown in Canton, China, had built a Chinese garden in Serangoon Road. It was resplendent with flora and fauna, and even unusual animals and birds. This is the story of Whampoa Garden.

Whenever I get to walk in one of the many wonderful lush gardens and parks we have in Singapore, I can't help feeling, as all fellow Singaporeans would, a deep sense of gratitude for the remarkable effort that has made it possible for us to enjoy so much nature in a city.

We are often told how much we owe this to our first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, who launched a national drive in 1963 to transform Singapore into a "garden city" by greening up the island with tree planting marked by an annual tree-planting day.

Over the years this "garden city" vision has evolved and expanded into one of "city in a garden", which will ultimately see Singapore become a "city in nature" going by the aspirations of our planners.

While we take great pride in the 162-year-old Singapore Botanic Gardens, recently listed as a world heritage site by UNESCO; Jewel, a themed garden at Changi Airport; and the iconic Gardens by the Bay as the shiniest testimonies of Singapore's love for garden culture, few of us stop to think how far back this rich horticultural tradition goes.

Of course some would readily name the 82-hectare Singapore Botanic Gardens built in 1859 at its present Tanglin site as the origin of Singapore's horticultural history, which itself had actually begun from an even earlier but short-lived Botanical and Experimental Garden proposed by Stamford Raffles in 1822.

A private garden for the public to enjoy

But we easily forget that for a small island, we have in addition a much richer heritage of gardening excellence known even beyond Singapore for many years from the mid-19th century. Just consider this extraordinary account of a most charming garden given by Song Ong Siang in One Hundred Years' History of the Chinese in Singapore published in 1923.

Much of this account is usually left out in most narratives about Singapore's horticultural heritage.

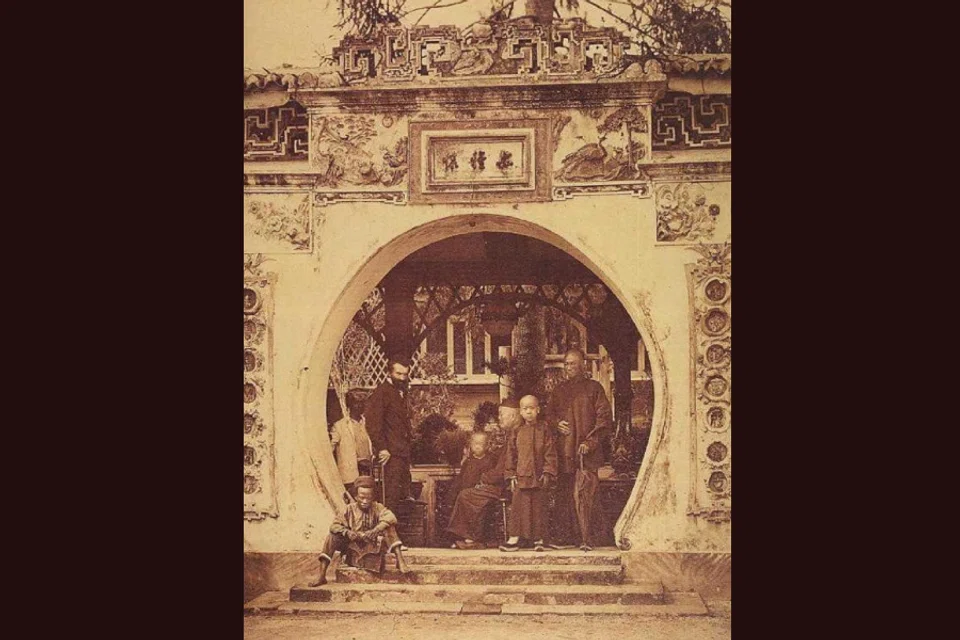

In the chapter The Third Decade, he writes: "[L]ong before public gardens were thought of he had bought a neglected garden 2 and 1/2miles out of town on the Serangoon Road. There he built a bungalow and the extensive grounds were at one time both an orange plantation, a fruit orchard and a Chinese garden laid out by horticulturists from Canton, and famous for its miniature rockeries, artificial ponds, aquariums and curious dwarf bamboos... There was displayed a wealth of horticultural products which were really admirable and unique. Plants from all available sources were collected and arranged with exquisite taste. Chrysanthemums, dahlias, lilies and a host of choicest flowers of South China contributed a brilliancy and picturesqueness that added an indescribable elegance to the sombre foliage of the luxuriant tropical plants all round.

"The well-planned paths were bordered with all varieties of brightly coloured flowering shrubs - the magnificent ixora, the numerous varieties of finely scented magnolia, the delicate blooms of many species of hibiscus and other plants too numerous to mention, contrasting with the beautiful flowers that emerged so gracefully from the ponds and streams. Water lilies of every colour decked the stagnant waters like stars shining forth in a dark night: while the white and pink blooms of the lotus surmounted in graceful elegance the majestic flowers of the Victoria Regia with their enormous circular leaves. There was also a choice selection of animals in the menagerie as well as a good collection of birds in the aviary."

Whampoa Gardens

This is a vivid description of the then much-celebrated Nam-sang Fa-un (南生花园) or Whampoa Gardens as it was known to the Europeans built by prominent businessman Hoo Ah Kay in 1840. Much of this account is usually left out in most narratives about Singapore's horticultural heritage. In the Singapore Botanic Gardens Heritage Museum, for instance, only a brief mention is made of Hoo being a keen garden lover who had a residence with "an exquisite Chinese garden" and played an important role in facilitating the colonial government's acquisition of the site for the Botanic Gardens. Despite the fact that a number of Whampoa Gardens' artefacts such as antique flower pots donated by Hoo's family were on display, one cannot find any references to Nam-sang Fa-un to give context to the relics in the otherwise excellent exhibition.

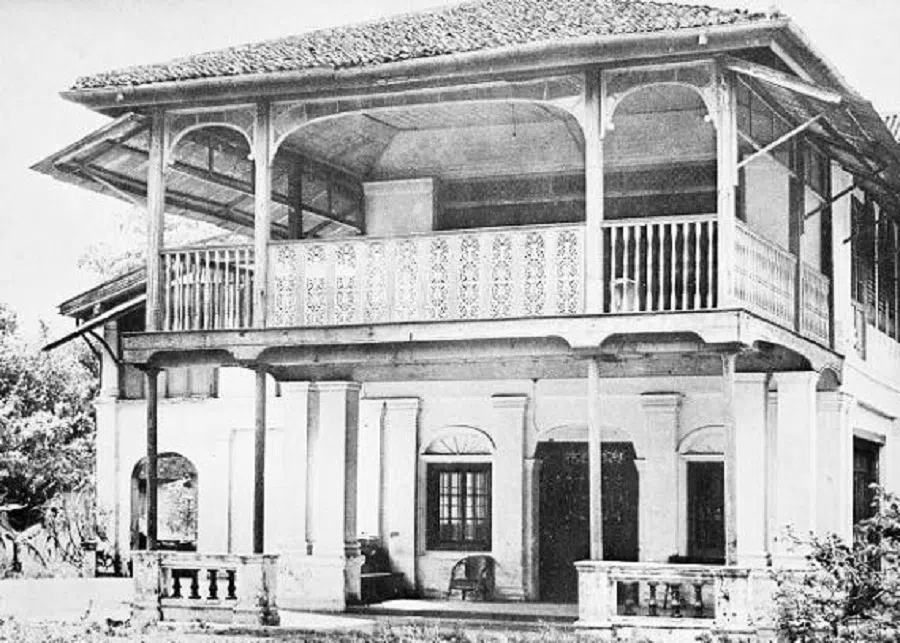

Whampoa House was bought over by Teochew millionaire Seah Liang Seah (1850-1924) who renamed it Bendemeer House, which was later demolished in 1964 to make way for urban development.

Born in 1816 in Huangpu near Guangzhou, China, Hoo arrived in Singapore in 1830 as a teenager to assist in his father's food supply business. After his father's death he took over Whampoa and Co. and expanded it into a leading ship chandler company. Hoo's command of English not only gave him an edge in business but also enabled him to serve in various civic and diplomatic positions such as those of the consul of Russia, China and Japan. But he was equally well known for his very popular Whampoa House where he often entertained visitors and welcomed the general public during Lunar New Year. After Hoo died in 1880, Whampoa House was bought over by Teochew millionaire Seah Liang Seah (1850-1924) who renamed it Bendemeer House, which was later demolished in 1964 to make way for urban development.

Hoo's legendary hospitality was extended to British naval officers and important guests from abroad. In 1867, a large dining room attached to the main house was completed to host a dinner for the returning Admiral Henry Keppel after whom the present Keppel Harbour is named.

According to his great-granddaughter Hoo Miew Oon, Hoo helped the colonial government start the Singapore Botanic Gardens because he had hoped to build a public garden to replace Nam-sang Fa-un that was open free of charge to the public.

In 1853 Hoo hosted a group of Russian visitors from a three-masted frigate Pallada whose voyage was carefully documented by Ivan Goncharov (1812-1891), a renowned novelist serving as secretary to Admiral Yevfimy Putyatin who led a two-year naval expedition to many countries.

Goncharov wrote a rather long chapter in his best-selling book The Frigate Pallada published in 1858, giving a detailed account of his journey to Singapore where he singled out Whampoa Gardens as though it was the greatest highlight of his one-week visit to this small island. The book became such a big hit in Russia that it went into its 10th edition by 1900 and was translated into various languages including Chinese in 1982.

Captivating flora and fauna

He described the garden in terms that are far more glowing than those of Song Ong Siang. Goncharov and his shipmates were so taken by the entire garden that he waxed lyrical over the exotic flora while lamenting his own description "for not coming up to even one-twentieth" of what he actually saw.

"Everything in here reflects the enduring beauty and elegance of nature without any trace of crudeness or vulgarity... urging one to stay and linger as one would relish a great work of art. Every tree, every shrub exudes its own colour and charm so that one would not hastily pass them by... thanks to Whampoa's master's stroke in the planning and design of the garden," writes Goncharov.

Marvelling at the magnificence that he said exceeded his expectations, he was particularly excited about the amazing variety of strange flowers and rare trees, especially the giant lotus and lilies in the pond.

Despite his misgivings about his stay being too long and the weather being too hot, Goncharov and his shipmates seemed to have spent their best moments in Singapore at Nam-sang Fa-un. He concluded the chapter with this statement: "I am happy to have seen Singapore but will not feel sad to leave. If asked to return I'd do so grudgingly."

...wouldn't it be far better if we simply properly acknowledge Hoo Ah Kay's pioneering role in our horticultural heritage and preserve the memory of his enchanting garden in our vision of "city in nature"...

Interestingly Singapore historian Kua Bak Lim suggested in an op-ed in Lianhe Zaobao (15 July 2011) that Nam-sang Fa-un be reconstructed to commemorate the contributions of Hoo Ah Kay.

Instead, I wonder, wouldn't it be far better if we simply properly acknowledge Hoo Ah Kay's pioneering role in our horticultural heritage and preserve the memory of his enchanting garden in our vision of "city in nature", lest we forget the debt we owe to this passionate garden lover whenever we enjoy a walk in our pleasant, lush green environment?

Related: How the 'tree' of Chinese writing united dialects, culture and people through the millennia | How the Shanghai Book Company enlivened Singapore's cultural scene | Chinese bookshops in Singapore: Art salons of the 1970s and 1980s | Liu Thai Ker and Ke Huanzhang: Urban planners are servants of the city | Architects Mok Wei Wei and Chang Yung Ho: Imagining and building a humane city

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)