From Beijing to the provinces: Can localising China’s narrative enhance its storytelling?

China has launched 26 international communication centres to share its story worldwide, distributing media content from within the country. But will this localised approach truly connect with a global audience? Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Daryl Lim reports.

“Our communication centre has a global IP network, so we can bypass the firewall to access the global network without using a VPN (virtual private network).”

Last month, the Greater Bay Area International Communication Center in Guangzhou’s Nansha organised a visit for 15 overseas media outlets, including Lianhe Zaobao and media from Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Hong Kong and Macau.

When introducing the hardware facilities, Niu Siyuan, the centre’s director, highlighted the centre’s unique selling point — its internet connection is not subject to the “Great Firewall”.

He also mentioned that since its opening in February last year, the centre has functioned as a bridge between the media on one side and local governments and businesses on the other, providing resource coordination and transmitting China’s voice to overseas audiences.

Central government’s focus on soft power

Established by the Publicity Department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Nansha District Committee, the Greater Bay Area ICC in Nansha is one of the many regional international communication platforms that have mushroomed in China over the past two years.

Tibet, whose status is often criticised by Western media, established an international communication centre (ICC) in September, becoming the latest provincial-level international communication platform. Based on statistics from the independent media think tank China Media Project, 26 provinces and municipalities in China have established ICCs as of 2022.

... the establishment of ICCs [international communication centres] in various provinces and cities shows that the task of telling China’s story has gradually shifted from the central government to the local governments. — Assistant Professor Selina Ho, LKYSPP, NUS

These ICCs are aimed at strengthening external publicity; shaping and spreading China’s image, culture and values globally; telling China’s story; and managing the negative narratives and reports about China in Western media.

Selina Ho, an assistant professor at the National University of Singapore (NUS)’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP), told Lianhe Zaobao that the establishment of ICCs in various provinces and cities shows that the task of telling China’s story has gradually shifted from the central government to the local governments. Various regions are also becoming important channels for external publicity, actively promoting international communication through economic and trade cooperation, diplomatic activities and people-to-people exchanges.

She said, “This is evolving into a ‘telling China’s story well’ national campaign.”

The CCP first proposed the need to “enhance culture as part of the soft power of our country” in its 17th Party Congress report in 2007, and to gradually build a comprehensive, multi-layered and broad external propaganda strategy in the following years, including accelerating the global expansion of Chinese state media to strengthen its discourse power.

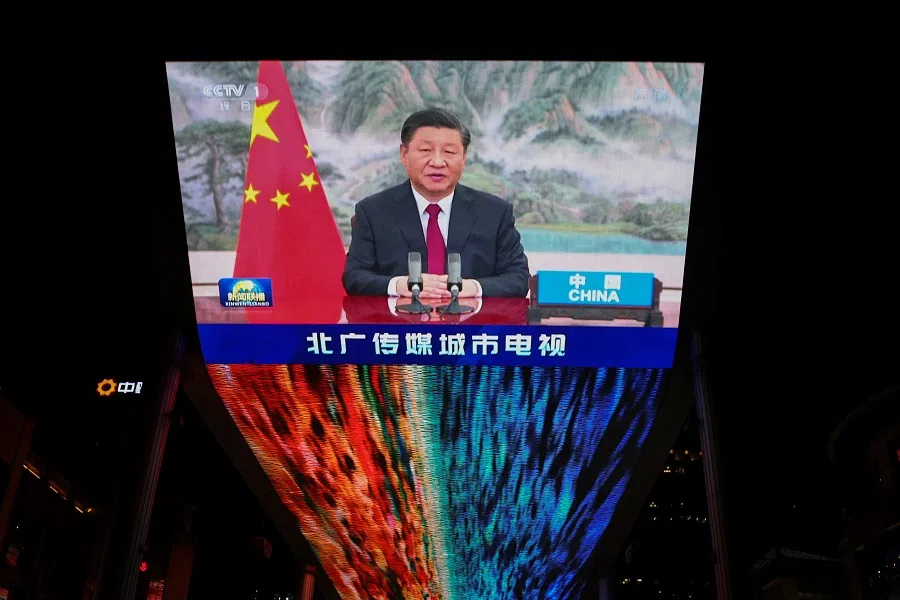

After Xi Jinping became the general secretary of the CCP in 2012, he immediately called on the CCP’s propaganda system to meticulously conduct external publicity work, innovate external communication methods and tell China’s story effectively. Subsequently, China’s external communication continuously expanded in scope, with increasingly diverse channels, even extending to social media platforms inaccessible within China.

Lianhe Zaobao found that Chinese state media such as CCTV News, China News Service, Xinhua News Agency and China Global Television Network (CGTN) joined Western social media platforms such as Facebook, X (formerly Twitter) and YouTube around 2013.

Ho pointed out that while China had previously focused on the development of hard power such as the economy and military, under Xi’s rule, the country has placed greater emphasis on intangible soft power, with the president focusing more on China’s ideological construction compared with any of his predecessors.

When speaking on accelerating the construction of China’s own discourse and narrative in 2021, Xi further proposed the need to “shape a reliable, admirable and respectable image of China” on the foundation of telling China’s story well.

... it is in fact the central government adding another layer of publicity on top of the existing structure, further amplifying the voice of propaganda. — David Bandurski, Director, China Media Project

Role of local governments and ICCs

China Media Project director David Bandurski said when interviewed that establishing more local ICCs is a direct response to this directive and represents one of China’s latest efforts to strengthen its external propaganda in recent years.

Bandurski thinks that while shifting the task of external publicity from the central government to the local governments may seem like “decentralisation”, it is in fact the central government adding another layer of publicity on top of the existing structure, further amplifying the voice of propaganda.

He said that the overall strategy is still led by the central government, but it is promoted and implemented by the propaganda departments and media groups at all levels.

In an interview, Chang Chih-chung, dean of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Kainan University in Taiwan, pointed out that local areas have more flexibility than central authorities in information dissemination. Local propaganda departments can collaborate directly with the local media, leveraging abundant regional resources such as tertiary students and corporate brands.

Moreover, the ICCs can tailor their objectives based on the local budget and focus on local cultural characteristics to showcase diverse content.

Greater Bay Area ICC director Niu shared that the centre would organise video competitions and invite foreigners living in the area to film videos as “international experience officers” to promote Nansha.

Moreover, in late September the centre hosted a group of overseas influencers, arranging visits to tourist attractions such as the Nansha Tin Hau Temple, as well as traditional Chinese craft experiences such as making Xiangyunsha fabric.

“We can accept suggestions and good intentions from friends, even if their views differ. However, we will never accept hostile slander. If someone deliberately distorts the facts, that is clearly not the behaviour of a friend.” — Niu Siyuan, Director, Greater Bay Area ICC in Guangzhou’s Nansha

Niu stated that the centre currently houses over 40 domestic and international media organisations, social self-media platforms and think tanks. He described these entities as forming a powerful public opinion matrix, making it a “flagship for external publicity” with international influence.

As for whether the centre can accommodate diverse narratives about China, Niu told Lianhe Zaobao that they welcome diverse reporting by various media, but the content must comply with Chinese laws and regulations, and adhere to journalism standards.

Niu commented, “We can accept suggestions and good intentions from friends, even if their views differ. However, we will never accept hostile slander. If someone deliberately distorts the facts, that is clearly not the behaviour of a friend.”

Too much propaganda?

Kainan University’s Chang observed that local centres have shown greater flexibility in fields such as culture and tourism, and that the diversity of Chinese society was effectively accepted by the outside world based on the results of social media.

He added that China’s increased efforts in external communication meant that audiences have more choices when receiving information, providing narratives about China that differ from Western perspectives.

However, Chang emphasised that if centres simply avoid discussions on sensitive topics by Western media and only highlight the scenic side of the regions, it would be difficult to dispel the external attention and criticism on these issues.

... as more centres join in the cause, the external propaganda efforts of provinces and cities will most likely continue to ramp up, and the oversaturation of such content may lead to information chaos. — Bandurski

He said, “If local centres merely toe the line in external publicity as dictated by the central authorities without considering local realities and audience feedback, the effectiveness of the publicity efforts may be limited or even counterproductive.”

Bandurski believes that it is both too early and quite difficult to assess the influence of ICCs across different regions. However, as more centres join in the cause, the external propaganda efforts of provinces and cities will most likely continue to ramp up, and the oversaturation of such content may lead to information chaos.

He analysed that China’s strategy is to flood the media environment with a large amount of content, with much of the content about China on social media originating from China, including the ICCs. However, many accounts lack transparency and do not indicate that they are from official sources, making it difficult for people to discern the nature of the related propaganda.

However, Bandurski stressed that strictly speaking China’s external publicity methods are not illegal. Many countries — including the US — adopt similar practices, such as inviting overseas media groups to visit Congress in Washington.

He added, “There is nothing inherently wrong about this, but when you take a step back and closely examine China’s methods, its one goal is very clear: to strengthen propaganda and shape China’s image, rather than for education or to enhance media capacity”.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “国际传播中心遍地开花 花式讲述中国故事”.