Beyond the blame game: Why US-China scientific cooperation on fentanyl is crucial

China should continue to demonstrate to the rest of the world that the “control of [illicit] drugs is essential to the future of humanity”, as reiterated in the preface of its white paper just published. Doing that entails continuous cooperation with all countries, the US included, says Chinese academic Zha Daojiong.

Alongside President Trump’s executive order on 1 February 2025, fentanyl became an issue-specific justification by the US to levy additional tariffs on Chinese exports. China rejected the linkage and responded with new tariffs on American exports.

However, China’s release of a white paper on fentanyl-related substances on 4 March — the same day the US implemented a second round of 10% tariffs citing the same justification — can be seen as a tacit acknowledgment of the US’s reasoning. One way to make sense of the ongoing impasse in positions between the two sides is to examine fentanyl — synonymous with illicit opioids in popular narratives — as a stand-alone issue.

A bigger problem in the US

In the US, unusual overdose deaths were traced to illicit fentanyl back in 1979 and called “China White” by street dealers. In the ensuing decades, outbreaks of fentanyl abuse were first traced to clandestine labs within the country. But since the early 2010s, more and more studies in the US began to conclude that import, mostly from China and Mexico, became the primary source of supply.

Fentanyl was first synthesised in China in 1972 and authorised for medical use two years later. Over the years, the country’s research agencies have reported only a limited number of cases of fentanyl abuse. Annual reports by the country’s National Narcotics Control Commission identifies the inflow of illicit drugs as the main source, but fentanyl is not a prominent item among them.

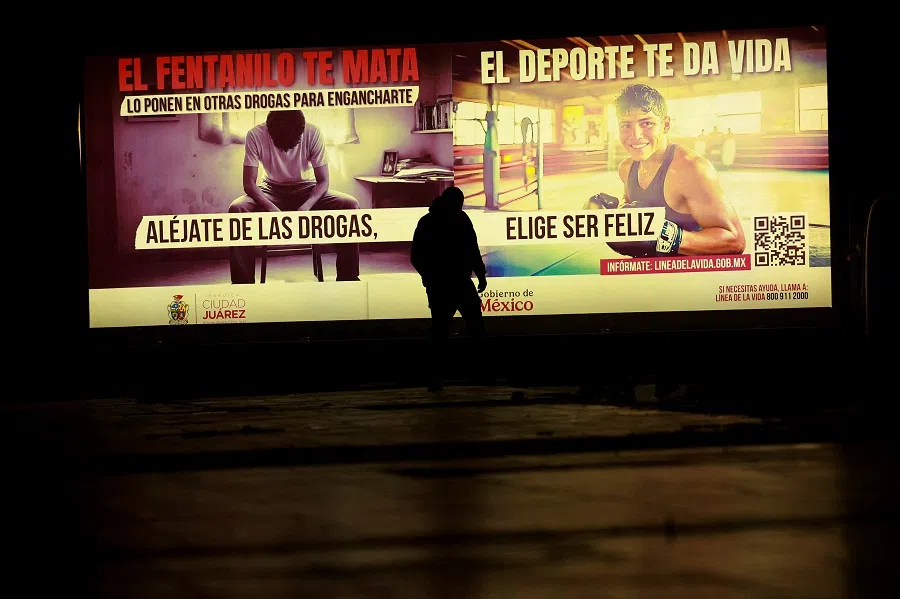

It is not easy to pinpoint the historical beginnings or market mechanisms for made-in-China fentanyl and fentanyl-related materials, including chemical substances that can be potentially used as precursors for manufacturing illicit drugs (“fentanyl precursors”), to end up in the US. Regardless, even just by casual observation of street scenes, it is unmistakable that fentanyl abuse is a more serious phenomenon in America than in China.

But the contrast in severity in no way whatsoever implies that China treats fentanyl abuse as irrelevant to its own societal interest.

But the contrast in severity in no way whatsoever implies that China treats fentanyl abuse as irrelevant to its own societal interest. Quite the contrary, with the world’s illicit drug market denying national boundaries, China has every reason to continue cooperation with the US and other countries across the world as well.

Distinction between legitimate and illicit fentanyl

As recorded in annual reports of the International Narcotics Control Board, a United Nations (UN) agency, fentanyl and fentanyl analogues are medical substances countries stockpile in their respective medicine supply chains. Worldwide, as a prescribed opioid, fentanyl is among the essential medicines list recommended by the World Health Organization for acute cancer pain, palliative care, and treatment of opioid dependence.

My purpose in restating such facts is two-fold. First, fentanyl, potent as it is (80 times that of morphine), and its derivatives are used as both human and veterinarian medicine. Their medical application requires strict regulatory oversight and compliance in practice. But as is true of other medicines, its diversion into non-medical use is an unfortunate reality as well.

In contrast, fentanyl analogs are illicit — and often deadly — alterations of the medically prescribed medicinal fentanyl. Fentanyl analogues are “designer drugs”, i.e. purposefully designed to elude law enforcement, to be traded in the narcotics markets. As such, projection of public health policy should make a clear distinction between legitimate and illicit fentanyl.

Second, deriving from the first, Chinese experts on pain management and their American peers have had over a half century of scientific and professional exchange on safe and responsible use of medicinal opioids. There is no moral justification for that US-China exchange to be curtailed due to shifts in overall sentiments — a “trust deficit” — between the two governments.

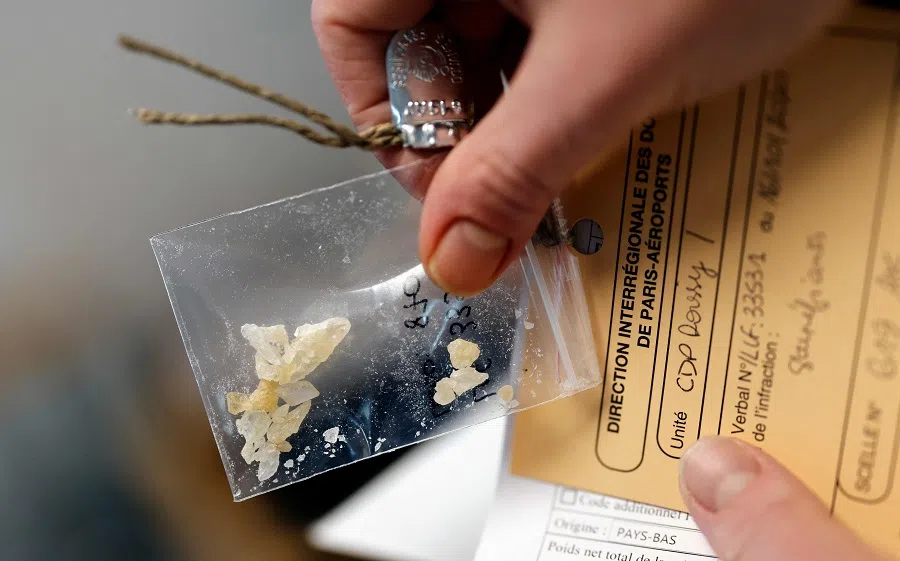

Due to the ease of concealment in packaging, international trafficking of fentanyl analogues and other illicit synthetic opioids are well suited for the internet age.

US-China law enforcement cooperation

Law enforcement agencies of China and the US have a long history of cooperation in combatting drug trafficking, before and after the establishment of formal diplomatic ties between the two governments. Understanding the track record and quality of cooperation, which now involves multiple agencies from both sides, is understandably challenging. This requires professional expertise that often goes beyond the reach of the general public.

The default mode of cooperation is working groups, since there has yet to be a judicial cooperation treaty. This leaves information exchange to be the low-hanging fruit for designated agencies. The agencies operate by observing respective domestic laws, which are in turn designed first and foremost to address issues under their respective jurisdictions.

Due to the ease of concealment in packaging, international trafficking of fentanyl analogues and other illicit synthetic opioids are well suited for the internet age. Online dissemination of novel, easier and more efficient synthesis methods aid the trade, discovery and manufacture of chemicals. Opportunities for legitimate e-commerce and online shopping can be and are used by drug traffickers as well. Adding to the complication is the emergence of cryptocurrency, which is a proven means for money laundering by criminals and their syndicates working together in defiance of border control in the usual sense of the term.

Chemical materials — the overwhelming majority of which have legitimate use in a broad range of industries worldwide — risk being used for manufacturing illicit fentanyl. Hence beginning in 2017, an increasing list of fentanyl precursors have been placed under the UN drug control system. On the one hand, American observations of the difference between the UN list and that of China is valid. On the other hand, it is also a fact that “street chemists” churning out illicit opioids prevail in the competition with law enforcement by being steps ahead of scheduling.

Here I must emphatically say that I am not suggesting that China should leave the state of affairs in dealing with fentanyl precursors as it is. Rather, there is space for the chemical science communities of both countries to continue their exchange to reach consensus based on pathological sciences.

... it is highly doubtful that the market effects of increased and/or sustained tariffs will lead to the lessening of drug abuse, in the US or any other country.

Tariffs as a (the) solution?

If, as specified in the Trump presidential executive orders, lifting the additional 20% tariffs on China is premised upon American certification of a resolution of the fentanyl crisis, there stands a good chance for the trade measure to be indefinite. Throughout its history as a country, the US (like China) has never stopped having to deal with drug abuse and drug trafficking. The resilience of the world narcotics market is such that the country’s war on drugs — including through curbing foreign sources of supply — can hope for its societal malaise to be less severe but not disappear.

What constitutes a public health crisis, the legal basis for taking measures on levying import tariffs, is by nature a political judgement. In addition, it is highly doubtful that the market effects of increased and/or sustained tariffs will lead to the lessening of drug abuse, in the US or any other country.

For China, the collective memory of enduring a century of foreign-supplied opium makes it difficult to dismiss outright the parallels the US is drawing today. Instead, empathy with what the American society is going through in dealing with its opioid abuse is essential for building goodwill, even if it fails to change the mind of American ideologies who accuse China of intentionally doing harm.

As the worldwide flows of natural, semi-synthesised and synthesised illicit drugs defy clear-cut narratives — certainly not a single-act “solution” — China acted correctly by rejecting the linkage between fentanyl/opioids and trade drawn in President Trump’s executive orders. Still, it should continue to demonstrate to the rest of the world that the “control of [illicit] drugs is essential to the future of humanity”, as reiterated in the preface of its white paper. Doing that entails continuous cooperation with all countries, the US included, at bilateral and multilateral levels to combat international drug trafficking.

Last but not least, it will be conducive for functional agencies of both governments, professional and academic entities and individuals in the know to work to educate the general publics of both countries about responsible practices in chemical and pharmaceutical industries, as well as the safe use of medicinal products. Greater levels of publicity about efforts at international cooperation will be helpful as well. In any case, the challenge of illicit drug control is common and involves far more than law enforcement and/or border protection.