Cool in the crossfire? Thailand amid major power competition

Thailand stands out in the region for its unruffled response to rising great power rivalry. Why so?

“Don’t Make Us Choose” (DMUC) is a common refrain in Southeast Asia as regional states are bearing the brunt of US-China rivalry and feeling forced to choose sides, even if the major powers claim otherwise.

ASEAN countries have had to adjust to shifting supply chains, minding tit-for-tat tariffs, and keeping an eye on minilaterals like the Quad, Squad and AUKUS. Some ASEAN countries like Vietnam and Thailand may benefit from the new “China plus one” strategies adopted on the production side of the house but others could face downstream disruptions.

Foreign policy driven by economic objectives

Yet Sino-US rivalry, along with affairs in Myanmar and Mekong, ranks low among Thailand’s foreign policy priorities, according to The Asia Foundation’s recent national survey on Thai public views on international issues. This differs from heightened regional worries and somewhat conflicts with Thailand’s desire to reclaim regional leadership, supported by 51% of respondents to the same survey who are informed about international issues (or IR-informed).

The Thai public prefers the country’s foreign policy to focus on economic and national security issues, with 93% of IR-informed respondents identifying economic growth as Thailand’s highest priority, followed by 77% ranking national security as the second-highest priority.

The curious question is why Thailand is an outlier in the region for its reaction to major power competition.

Observers may posit that this stems from Thais being inward-looking following decades of domestic political instability. One could even argue that Thais — diplomats included — are inherently inward-looking, given Thailand’s uncolonised past. Another contributing factor is likely the perception that Thailand can still maintain a satisfactory balance between the US, its treaty ally, and China, its comprehensive strategic partner.

Without the Communist threat, Thailand no longer poses a credible existential threat that requires US security cover.

Ups and downs in US-Thai relations

US-Thai relations have witnessed greater volatility and tend to fluctuate according to changes in the US administration and each new administration’s reactions to Thai politics. The Obama administration’s downgrading of US-Thai relations, which drove Thailand closer into China’s orbit, was a response to Thailand’s 2014 coup. This was followed by an uptick in relations during the Trump administration, as evidenced by army commander-turned-premier Prayuth Chan-ocha’s 2017 White House visit, followed by a seemingly sluggish bilateral trajectory during the Biden administration.

There have been signs of improvement under Biden, however, as seen through the 2022 communique on strategic alliance and partnership and strengthened defence cooperation. Thailand’s interest in buying American jets, several US port visits to Thailand, and Exercise Cobra Gold’s expanding scope are palpable advancements. Still, the alliance falls short of its former heights in the 1960s-1970s, when staunchly anti-Communist Thailand was the darling of US foreign policy wonks and practitioners.

Without the Communist threat, Thailand no longer poses a credible existential threat that requires US security cover. This shift has prompted questions among observers and particularly US policymakers as to whether Thailand is content to remain passive or if Thailand would exercise greater agency in shaping a more comprehensive approach to the US.

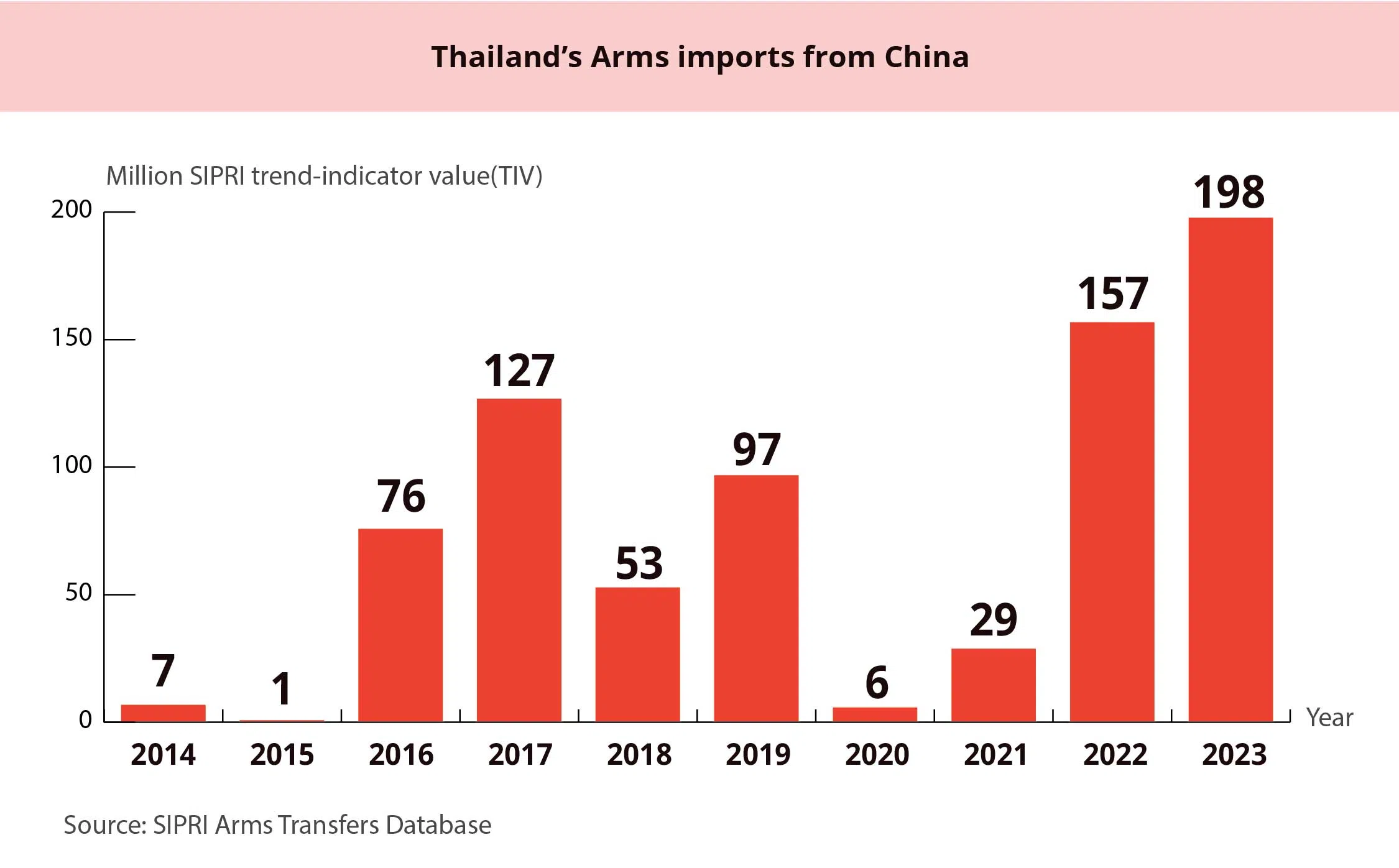

In contrast, Sino-Thai relations have remained relatively steady, notwithstanding changes in government and the COVID-19 pandemic. The Prayuth government (2014-2023) witnessed a surge in Thailand-China defence cooperation, evidenced by expansive and more frequent military exercises, and Thailand’s increasing purchases of Chinese military kit. Data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) reveal a steady rise in Thailand’s arms purchases from China, except for a noticeable dip in 2018-2021, a period marked by improved US-Thai relations and the pandemic.

One issue that could cause Thailand to gravitate back to the US is the potential Chinese military buildup at Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base in the Gulf of Thailand.

Relations with China key for economic growth

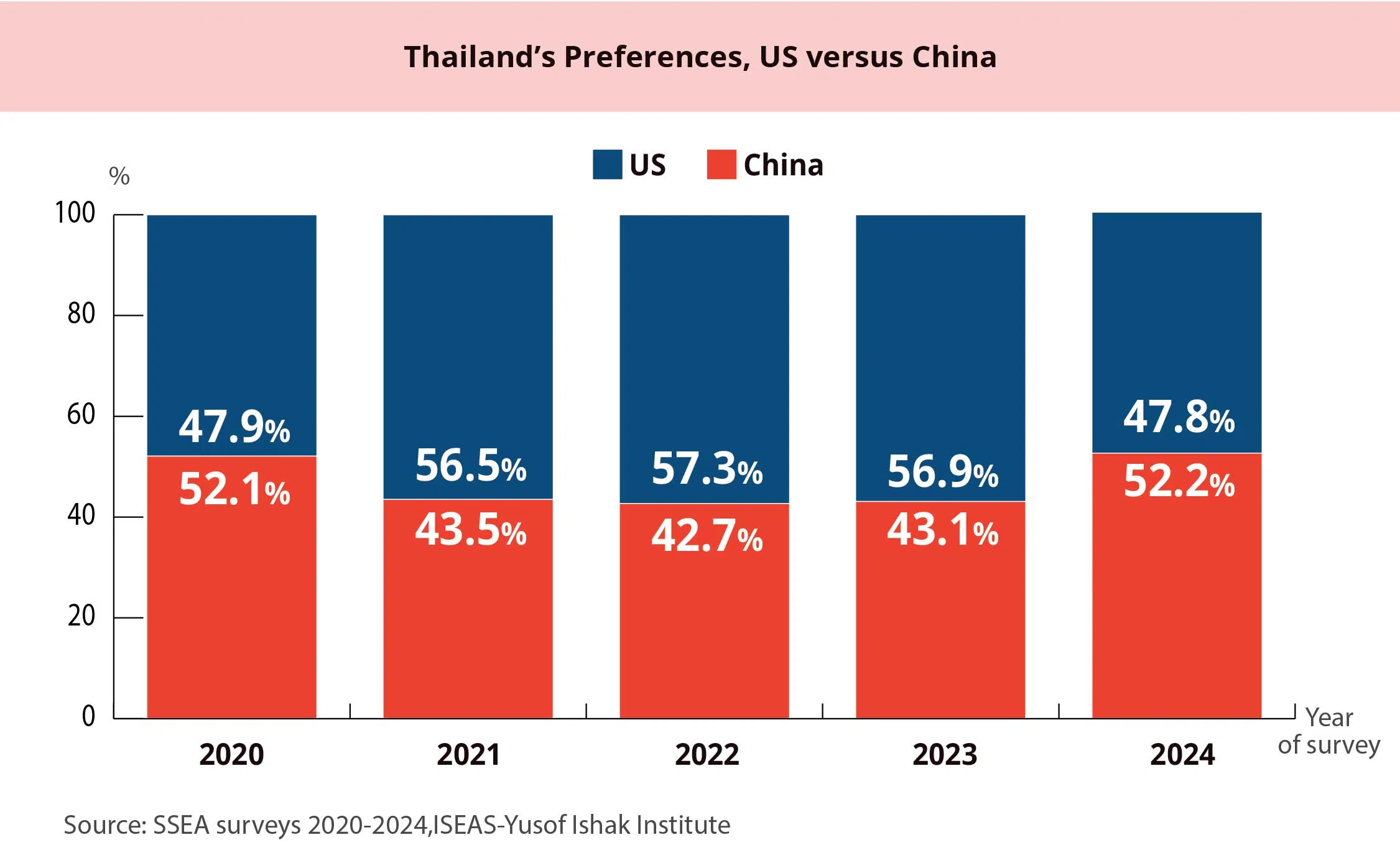

The current civilian-led Srettha Thavisin administration regards China as pivotal in boosting Thailand’s lacklustre economy, whether through tourism or electric vehicle investments. Echoing the government’s view, a recent Pew research survey tracking Chinese impact on the national economies of 35 countries reveals that the Thai public perceives Chinese economic influence most positively among middle-income countries. Similarly, Thai elites responding to the State of Southeast Asia (SSEA) surveys by ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, when asked a hypothetical question on being forced to choose between the US or China, chose China over the US in 2020 and 2024.

One issue that could cause Thailand to gravitate back to the US is the potential Chinese military buildup at Cambodia’s Ream Naval Base in the Gulf of Thailand. While Thailand is generally welcoming of China’s economic influence, having Chinese military presence on its doorstop is undesirable, especially considering the unresolved and highly complex Thai-Cambodian maritime dispute in the area. The disputed 27,000-square-kilometre area, originating from different interpretations of the 1907 Franco-Siamese Treaty, has significant oil and gas potential. Thailand’s approach to Ream should thus be closely observed.

The upcoming US presidential elections, now upended by Biden’s decision to pull out and endorse his vice president Kamala Harris, but still accompanied by prospects of a second Trump term, may cause sleepless nights among regional elites. However, this does not appear to be a frightening spectre for the Thais, underscoring Thailand’s outlier status. Although Thailand has debated the implications of Trump’s isolationist policies on its economic prospects, security and alliance concerns have been sidelined.

The challenge going forward is to advance regional leadership without upsetting the delicate equilibrium between major powers. This is difficult for Thailand, with its recent passive diplomacy and avoidance of choosing sides.

Thailand’s current biggest security issue is Myanmar, and that has been managed largely through cooperation with fellow ASEAN members, China and India, and to a very limited extent, the US (regarding cooperation on Myanmar asylum seekers). Thai decision makers seem prepared to work with whoever is in the White House.

Given Trump’s apparent disinterest in democracy promotion, a Trump presidency may not be entirely negative for politically turbulent Thailand. Interestingly, conversations among Thai netizens, for instance on a popular Thai-language forum Pantip, indicate a degree of acceptance of the questionable narrative — fuelled by Trump himself — that Trump’s government would avoid starting new wars and might be better for global stability.

The challenge going forward is to advance regional leadership without upsetting the delicate equilibrium between major powers. This is difficult for Thailand, with its recent passive diplomacy and avoidance of choosing sides. The Srettha administration’s one-sided emphasis on economic matters without stronger strategic positions on critical issues like the South China Sea, the Taiwan Strait, and Myanmar – all of which affect ASEAN – may not be enough to assert regional leadership.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)