Will Trump become America’s Deng Xiaoping — or its Gorbachev?

Trump exposes America’s deep political and strategic dysfunction. His disruption could either spur institutional renewal and recalibration — like Deng Xiaoping— or deepen division and decay, like Gorbachev, observes academic Tan Kong Yam.

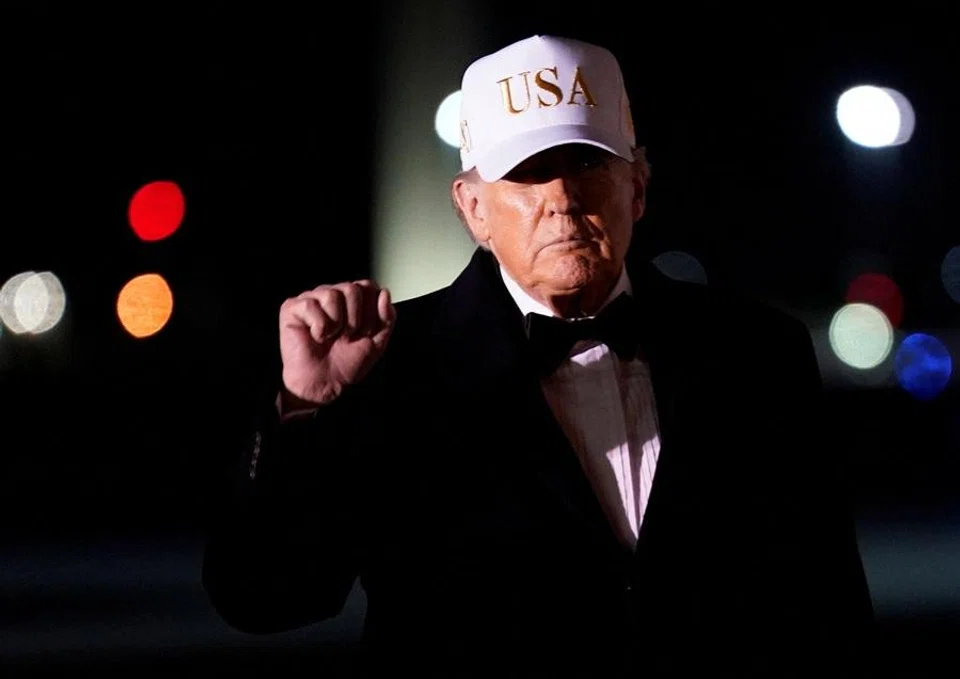

Whether US President Donald Trump will become America’s Deng Xiaoping or its Mikhail Gorbachev is not a question of personal character, but of historical function.

Both Deng and Gorbachev had emerged at moments when the foundations of their respective systems’ legitimacy had been exhausted: structural economic stagnation, an ossified elite and widespread public disillusionment. The difference between them: one preserved the system by transforming it, while the other sought reform but inadvertently caused the system's collapse.

Today, Trump occupies a similarly ambiguous place in American history. He is not an institution designer with a clear blueprint, but rather a disruptive figure — one who forces the US to abandon its long-held, self-comforting illusions about itself and the world.

In an unusually candid interview with the Financial Times in July 2018, former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger remarked that Trump might be an “accidental” historical figure — someone who marks the end of an era without fully understanding what he is bringing to a close. Trump may lack systematic strategic thinking or a clear plan for renewal, but by challenging alliances, institutions and norms long regarded as America’s “natural moral extensions”, he has exposed the profound contingency and fragility of the post-Cold War international order.

Kissinger warned that the real danger lies not merely in disorder but in “misaligned adjustment”: a fractured Atlantic world, Europe gradually drifting towards Eurasia, China returning to its historical role as the “centre of tianxia (天下, all under heaven)” and the “chief adviser to all humanity”, while the US risks becoming a geopolitical island — still powerful, yet increasingly isolated.

Trump is not merely a populist provocateur or an accidental historical aberration, but a symptom of the long-accumulated dysfunction in America’s democracy, political economy and system of global leadership.

This sense of historical rupture is crucial. Trump is not merely a populist provocateur or an accidental historical aberration, but a symptom of the long-accumulated dysfunction in America’s democracy, political economy and system of global leadership. His rise shows that the old formula — liberal internationalism abroad, financialised globalisation at home and elite-driven democracy — no longer commands broad social consent.

Trumpism as a ‘diagnosis’, not a ‘cure’

The interpretation of Trump’s rise offered by right-wing media commentator Tucker Carlson provides a crucial perspective for understanding domestic US politics. He said bluntly in 2018, “Happy countries don’t elect Donald Trump president.” From this perspective, Trump’s victory was not an endorsement of a coherent policy platform, but a cry of protest — an attempt by voters to jolt an establishment that had long been insulated from the consequences of its own decisions.

At the core of this judgement lies the collapse of the long-held American belief in a “level playing field”. For decades, the legitimacy of US capitalism rested not on equality of outcome, but on equality of opportunity. Extreme wealth disparities were tolerated because wealth was widely seen as open and mobile, rather than hereditary and closed.

The rituals of democracy remain — elections, freedom of speech, party competition — but their substance has been hollowed out by money-driven politics and lobbying mechanisms.

However, massive amounts of research have shown that income growth for the bottom half of the US population has stagnated for decades. Wealth, political influence and cultural insulation are increasingly concentrated at the top. Education and credentials no longer guarantee social mobility, and political participation no longer reliably translates into policy influence.

The rituals of democracy remain — elections, freedom of speech, party competition — but their substance has been hollowed out by money-driven politics and lobbying mechanisms.

Deng Xiaoping, Gorbachev and systemic crisis

Placing Trump alongside Deng and Gorbachev is no casual comparison. Deng confronted a Communist Party that had lost its credibility in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. His response was pragmatic, gradual and highly restrained: opening up the economy without liberalising the political system; tolerating inequality so long as overall living standards improved; and preserving the party’s authority while abandoning ideological purity.

Deng did not revive Maoism, but instead replaced it with a hybrid system capable of generating growth, stability and a new source of legitimacy.

Meanwhile, Gorbachev pursued political liberalisation and economic reform simultaneously, but gravely underestimated the extent to which weak economic performance, eroding legitimacy, rising nationalism and elite rivalry had already hollowed out Soviet cohesion. The Gorbachev-style reforms exposed problems far more quickly than they could be remedied, resulting not in renewal but in dissolution.

“America First” is increasingly interpreted abroad as “America alone”.

Where does Trump sit on this spectrum? Is he a ruthless realist who rips apart ideological illusions to force the system to adapt to reality, or is he a reckless destroyer who accelerates disintegration without constructing any viable alternative?

Foreign policy: from system manager to transactional great power

These questions are particularly evident in foreign policy. Postwar US dominance rested on an implicit bargain: the US provided security, market access and monetary stability, while its allies accepted US leadership and a rules-based order that — while imperfect — was highly predictable.

Trump openly challenging this arrangement represented a fundamental departure from traditional realist logic. Historically, great powers have tended to favour rules because they are usually the ones who set and enforce them, and because the rules serve their strategic advantages.

... China’s strategy — there is no need to overthrow the existing system; it is enough to weaken its capacity for resistance, erode alliances and secure neutrality on key issues — particularly Taiwan.

“America First” is increasingly interpreted abroad as “America alone”. In the first year of Trump 2.0, relations between the US and its allies deteriorated acutely because of tariff wars, US withdrawals from multilateral institutions, contentious rhetoric and the transactionalisation of security policy. This was most evident in Europe — European trust in US security guarantees has fallen to its lowest level since WWII.

From Beijing’s perspective, this shift brings opportunities. Chinese analysts do not interpret Trump’s policies as a new round of containment, but as a tacit recognition by the US of the limits of its capabilities. Rather than viewing Washington as pursuing ideological confrontation, it is more accurate to see it moving toward transactional coexistence, selective technological restrictions and pragmatic bargaining.

This judgement underpins China’s strategy — there is no need to overthrow the existing system; it is enough to weaken its capacity for resistance, erode alliances and secure neutrality on key issues — particularly Taiwan.

Financial Times columnist Janan Ganesh pointed out that the most dangerous phase for a great power is not its rise or its peak, but its period of relative decline, as status anxiety drives erratic behaviour. The US was at its most generous when it was strongest: the 1948 Marshall Plan laid the foundations for Europe’s postwar recovery. As its relative advantage has declined, US behaviour has grown more coercive. Hence, Trump’s policy swings reflected a deeper “loss framing” mindset, oscillating between bluster and weary retreat, between coercion and pullback.

Internal instability and risk of disintegration

Domestically, the US faces multiple high-risk pressures at once: too many elites chasing too few opportunities, growing poverty among ordinary Americans, mounting fiscal strain and eroding trust in institutions. The polarisation of identity politics has turned political competition into a struggle for survival. Trump is not the root cause of these problems, but by normalising the violation of norms, weakening institutional legitimacy and depicting political opponents as enemies, he has accelerated this process.

Trump’s political success stems from his accurate grasp of real fractures in the American social contract. But the core tools he employs — sweeping tariffs and mass deportations of migrants — tend to push prices up, disrupt supply chains and shrink labour supply. Without complementary compensation policies, they would ultimately squeeze the working class. The recent fatal incident in Minneapolis involving federal law enforcement is a sign of the deepening constitutional and moral crisis in the US.

If his [Trump’s] disruptive actions ultimately spur institutional renewal, social rebalancing and strategic recalibration, he may unintentionally move closer to Deng.

Will Trump become the US’s Deng Xiaoping or its Gorbachev? I am deliberate in not offering a definitive answer. Trump has indeed identified real problems: elites detached from reality, unsustainable globalisation, hollowed-out democracy, as well as over-extension of hegemony. But identifying problems is not the same as solving them.

In the end, history will judge him not by his intentions but by his outcomes. If his disruptive actions ultimately spur institutional renewal, social rebalancing and strategic recalibration, he may unintentionally move closer to Deng. If, instead, they deepen division, chaos and the erosion of the rule of law, the comparison to Gorbachev would be more apt.

What is certain, as Kissinger warned, is that the US is in a profoundly perilous historical moment. Trump was not the cause — but he may well determine whether this period ends in renewal or disintegration.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “特朗普会成为美国的邓小平还是戈尔巴乔夫?”.