Why China’s young people are choosing to leave

Amid the gloomy employment prospects and unpleasant work environment in China, many youths are seeking opportunities overseas. Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Li Kang finds out that even with narrowing migration pathways and expected hardships abroad, Chinese youths are determined to leave.

Bo has been planning for three years to emigrate overseas. He intends to pursue a new career as a caregiver in Australia; if that doesn’t work out, he will go to France to join the Foreign Legion.

In an interview after getting off work at 11 pm, he spoke with evident exhaustion, “If I don’t leave now, it will only get harder.”

Lie flat, join the involution or leave

Bo works in recruitment at a Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE). Over the past few years, he has seen repeated cutbacks in hiring, making him increasingly anxious about employment prospects. At his company, in 2022, 15 people were hired from 400 résumés for a position with a monthly salary of 3,000 to 5,000 RMB (US$430 to US$715); by 2023, only eight were selected from 1,000 applicants.

He told Lianhe Zaobao, “Young people today have three paths: lie flat, join the involution or leave. The track for involution has already collapsed, and even the track for leaving is one step away from crumbling. So I have to speed things up and pray that I can escape before everything falls apart.”

... those seeking advice range from undergraduates at Peking University to IT professionals in their 30s who, after being laid off, are considering going overseas to work as plumbers or welders.

With China’s youth unemployment rate hovering at around 17%, many post-2000s youths like Bo are turning their job search overseas. They have become another group following after China’s elite and attempting to “run” abroad (润, which has the same pronunciation as the English word “run”, referring to an exodus from China to other countries).

Overseas student Yong Haonan, 18, has a different perspective. Since April last year, he has been posting videos introducing ways for people to work and immigrate abroad, country by country. He has garnered nearly 30,000 followers in just a few months.

At the same time, Yong has also set up online discussion groups, with nearly 4,000 members since the groups were launched in September 2025. He said members range from 16 to 35 years old, with most holding undergraduate or junior-college degrees, and their primary concern is obtaining first-hand information about overseas job opportunities and immigration.

To avoid attracting excessive attention, Yong has named the groups “language learning exchange groups”. Members can also arrange one-on-one consultations with him; those seeking advice range from undergraduates at Peking University to IT professionals in their 30s who, after being laid off, are considering going overseas to work as plumbers or welders.

Unlike expensive migration agencies, Yong does not set a price for his consultation services. Clients tip at their own discretion, anywhere from a few RMB to 50 or 60 RMB. He said, “My goal is to help a new generation of Chinese youth, anxious about unemployment, to go out into the world.”

Pay cuts for overseas job seekers

Guan, 28, has already left the country. After sending out 200 to 300 resumes in 2025 without finding a suitable position, he changed his approach. Within a month, he secured a finance role on an overseas assignment in Indonesia.

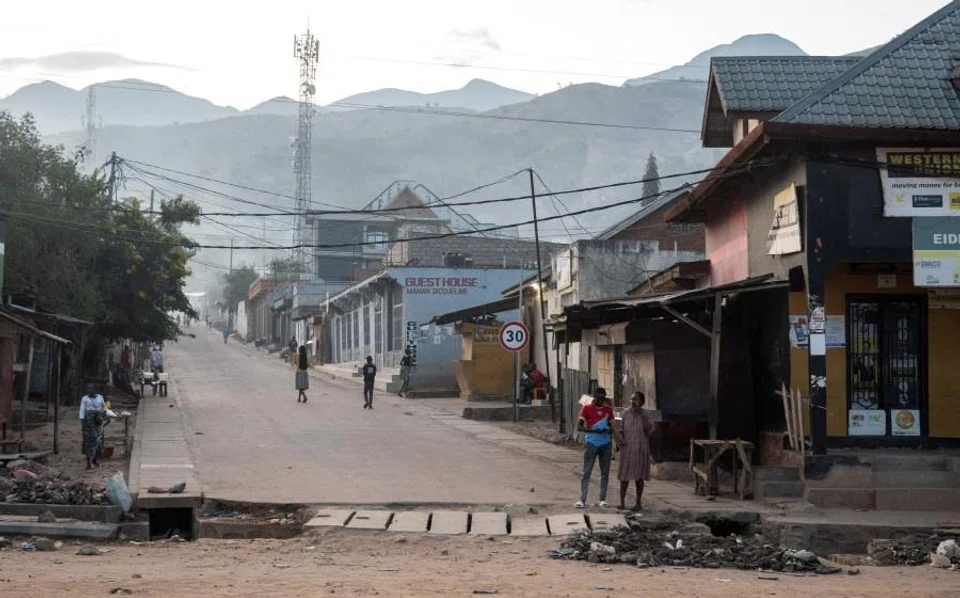

After working in Indonesia for a year, Guan was dispatched again last October to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which is still embroiled in conflict. Shortly after arriving in Africa, he contracted malaria.

“Ten years ago, being posted to Africa with an annual salary of over one million RMB wasn’t unusual. Now, even with a monthly salary of just over 10,000 RMB, employers have no trouble finding people.” — Guan, a young Chinese working abroad

When interviewed, Guan said helplessly that he chose Africa because he could save money “two to three times faster than in Indonesia”, allowing him to quickly accumulate “start-up capital” in preparation for the next step — emigrating to Germany.

However, as more people seek jobs overseas, competition for overseas postings has intensified and salaries have dropped sharply. Guan said, “Ten years ago, being posted to Africa with an annual salary of over one million RMB wasn’t unusual. Now, even with a monthly salary of just over 10,000 RMB, employers have no trouble finding people.”

Bo, who works in human resources, is even more sensitive to changes in overseas job opportunities. Offhand, he rattled off the occupation shortage list for Australia’s various states. Early childhood education — one of the “three pillars of migration” alongside nursing and social work that make the list almost every year — has become oversupplied in recent years.

In addition to attending ideological briefings and party meetings on rest days, the company also connects to employees’ personal mobile phones via data cables to scan their social media activity every week.

The narrowing of migration pathways once left Bo feeling lost, but he ultimately made up his mind to leave. He said, “Whether escaping will be better or not, can you accept the present situation? I can’t.”

Social and political anxieties as push factors

In fact, economic prospects are only part of the reason. As conversations deepened, many interviewees pointed to social and political anxieties, rather than material considerations alone, as the pressures that ultimately pushed them to leave.

Bo admitted that pessimism about future employment prospects was one factor, but what truly crushed him was the working environment at the central SOE. In addition to attending ideological briefings and party meetings on rest days, the company also connects to employees’ personal mobile phones via data cables to scan their social media activity every week.

During one such inspection, Bo was found to have donated cryptocurrency to Ukraine. He was subsequently required to write a self-criticism, and more than 800 RMB was deducted from his monthly salary of 2,600 RMB as punishment.

Bo initially thought the matter was over but a colleague reminded him that the incident had become a “stain” on his record. He was no longer regarded as “one of us”, and his chances of promotion had become extremely slim.

Disillusionment with society

Xu Quan, a current affairs commentator based in Taiwan, told Lianhe Zaobao that Chinese people have traditionally been deeply attached to their homeland. When people from such a society begin to plan their futures around “leaving the country”, he argued, the deeper question is what has gone wrong within Chinese society itself.

Xu said that young Chinese seeking work overseas today are not only willing to take up manual or service jobs, but are also prepared to go to non-traditional destinations such as South America and Africa. “This reflects the depth of their disappointment with the current state of society,” he said.

He said that young people’s inability to see prospects for upward mobility is not new, but has become particularly pronounced this year. The repeated spectacle of vested interest groups “flaunting power” and “boasting privilege”, he argued, has inflicted a profound psychological blow on ordinary citizens.

Citing a string of recent controversies — from the Dong Xiying incident last April, in which a trainee doctor allegedly rose through China’s top medical institutions using forged transcripts, plagiarised research and family connections; to the “sky-high earrings” controversy in May, when a teenage actress posted photos wearing earrings reportedly worth millions of renminbi, prompting questions about the legitimacy of her wealth given her family’s civil-servant background; and the recent furore over a 26-year-old doctoral supervisor at Zhejiang University — Xu said these cases point to the emergence of a “closed loop” among China’s privileged class, one that monopolises social resources and leaves little room for entry by lower- and middle-income groups.

“In the end, what they are left with is little more than the scraps and remnants of available resources.” Xu said.

A global phenomenon

Fu Fangjian, associate professor at the Lee Kong Chian School of Business at Singapore Management University, offered a different perspective. He pointed out that the sense of powerlessness felt by today’s young people is not unique to China, but a global phenomenon, with young people in the US also facing severe employment pressures.

He said that while improvements at the macro level are necessary, for individuals caught in the currents of their time, “difficulties will always exist. In that context, personal effort becomes even more important.”

Fu believes that Chinese young people choosing to leave may not necessarily be a bad thing. If domestic competition has become excessively intense, he said, it may make sense to change environments. “As the old saying goes, ‘A moving person thrives; a transplanted tree dies.’”

Fu added that Chinese trade now reaches more than 190 countries worldwide, and if young people follow the country’s broader strategy of going global, “taking a gamble might just allow them to fight for a better future for themselves”

As for whether life abroad will truly be better, Xu believes those who make such a choice are not doing so without anticipating hardship. He said, “They have weighed the difficulties and still choose to leave, that shows just how determined they are.”

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “通道收窄前途迷茫 中国青年“润”出海寻出路”.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)