[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?

A thawing Northern Sea Route (NSR) is forcing a rethink of global shipping, promising shorter voyages and lower costs. What this means for Singapore’s role as a maritime hub is now under scrutiny, as Lianhe Zaobao senior business correspondent Lewis Ong Yong Huat speaks to industry insiders and academics to find out more.

In just 21 days from September to October 2025, a Chinese container vessel called Istanbul Bridge arrived at Felixstowe, the UK’s largest container port, at the end of a roughly 7,500-nautical-mile journey from Ningbo, China. It had made use of the Northern Sea Route (NSR).

There is a significant difference, given that the traditional route via the Suez Canal covers about 11,000 nautical miles and typically takes 40 to 50 days. Yet the Istanbul Bridge has not taken the NSR since then — this begs the question, why?

Of the over 11 billion tonnes of maritime trade recorded globally per annum, only about 0.35% or tens of millions of tonnes go through the Arctic routes presently.

Not a preferred route for all

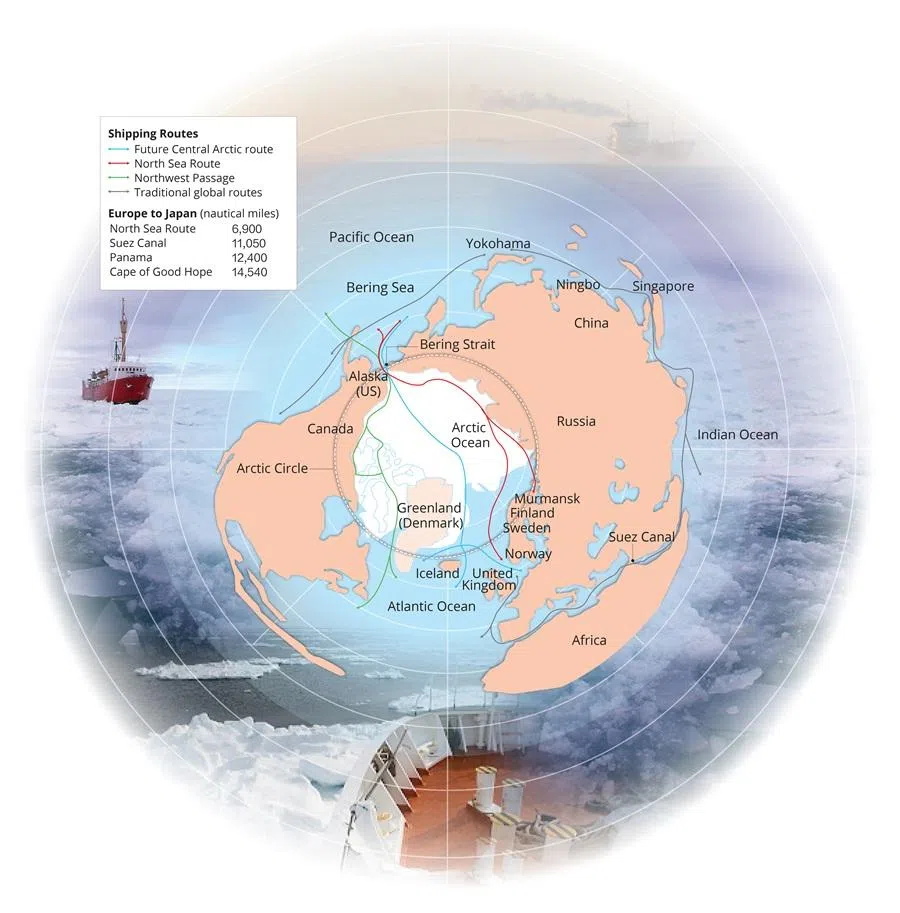

The NSR is one of the Arctic routes. Passing along Russia’s coastline, it is also the most likely to be developed first.

Punit Oza, president of the Institute of Chartered Shipbrokers (ICS), told Lianhe Zaobao that a journey from Murmansk, Russia, to Yokohama, Japan, via the Suez Canal would span 12,840 nautical miles and take about 40 days (plus two days in canal transit) at a speed of 13 knots; taking the NSR instead would reduce the distance to 5,770 nautical miles and the number of days to about 19 at the same speed.

“This shorter route translates into approximately 50% less sailing time while substantially decreasing fuel consumption and CO2 emissions from maritime transport. So, from the economic perspective, it is a no-brainer. However, operationally and geopolitically, it is not a preferred route for all,” he said.

Yuen Kum Fai, an associate professor at the Nanyang Technological University (NTU)’s School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, highlighted several issues. The cost to operate in the NSR is currently quite high due to the requirements of special-class vessels, as well as higher insurance premiums resulting from higher risks of accidents.

Why the Arctic isn’t ready yet

Of the over 11 billion tonnes of maritime trade recorded globally per annum, only about 0.35% or tens of millions of tonnes go through the Arctic routes presently. The percentage is small, partly because the NSR is navigable only for a few months in any given year, and icebreaker escorts are required.

The throughput is nowhere near what the Strait of Malacca handles. After all, 40% of global trade, including 80% of China’s crude oil imports and much of the energy supplies to Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, passes through it.

However, with rising global temperatures and the melting of the polar ice cap, might the Arctic Ocean soon be navigable without icebreakers?

Year-round open water for commercial shipping is unlikely in the near term, and will depend on continued trend of global warming, according to Samrat Bose and Christina Zhuang, a partner and senior manager respectively at Monitor Deloitte, Deloitte Southeast Asia.

“In the future decades ahead, if there is greater polar ice melting, this route could become more viable.” — Associate Professor Goh Puay Guan, Department of Analytics and Operations, NUS Business School

The fact is: global “warming” leads to extreme temperatures not only on the high end, but also on the low end.

It is tough to predict when the NSR will become navigable throughout the year, said ICS’s Oza. “The key is the icebreakers and how effective they are. They are quite expensive to use, so the question of how many to use and how long to use them creates cost uncertainty and also operational uncertainty, especially during the ‘twilight period’ — the changeover period between summer and winter and vice versa,” he added.

Goh Puay Guan, an associate professor at the Department of Analytics and Operations, National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School, puts it plainly, “In the future decades ahead, if there is greater polar ice melting, this route could become more viable.”

However, using an Arctic sea route as a major shipping lane is not just about the waterway itself, but also the port and logistics infrastructure. These would require massive investments, infrastructure and ecosystem build-up, as well as sufficient volume passing through to justify the commercial investments. In Goh’s opinion, the NSR will be more of a “niche offering” in at least the next decade.

According to Wong Meng Yew, global trade advisory leader at Deloitte Singapore and Southeast Asia, most credible projections suggest that seasonally ice‑free Arctic summers may occur between 2035 and 2050, lasting perhaps two to four months each year.

Year‑round, ice‑free commercial navigation remains highly speculative. The climate factor aside, the Arctic still needs to be adequate in various essentials, such as port infrastructure and service ecosystems.

... should the Arctic routes be made fully navigable by 2050 and capture a substantial share of Asia-Europe trade by mid-century, the reliance of global commerce on traditional chokepoints such as the Strait of Malacca and the Panama Canal may gradually diminish.

Despite the great uncertainty, should the Arctic routes be made fully navigable by 2050 and capture a substantial share of Asia-Europe trade by mid-century, the reliance of global commerce on traditional chokepoints such as the Strait of Malacca and the Panama Canal may gradually diminish.

Northern Europe, North Asia and Russia to benefit from upheaval in bulk trade

As Monitor Deloitte’s Bose and Zhuang see it, the resultant shortening of transit times could reduce inventory carrying costs, with potential downstream price effects if carriers pass on their savings. “However, Arctic shipping remains at a very early and largely explorative stage,” they said. “In the near to medium term, traditional trade lanes will remain dominant.”

If the NSR becomes widely used, it could be a big game changer for both dry and wet bulk trade. But there is still a catch, as foreseen by ICS’s Oza: “The container lines that operate on a pre-determined schedule and multiple port calls will still prefer the Singapore and the Strait of Malacca as they can service a greater amount of customers, loading and unloading containers en route [at] multiple ports.”

Countries that are geographically closer to the Arctic routes and closely linked to Europe-Asia trade, such as Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, the UK and Scandinavian nations, are the main potential beneficiaries of lower freight prices.

According to Joyce Low, an assistant professor for Operations Management (Education) at the Singapore Management University (SMU)’s Lee Kong Chian School of Business, these countries are most likely to use the routes for electronics, machinery, vehicles and consumer goods in certain seasons. Their export costs to Asia may also fall.

... players in Southeast Asia, South Asia and Africa would be adversely affected, since Arctic routes bypass Southeast Asia and cargo may no longer transit through their ports. Some shipping services may also be reduced.

Similarly, thanks to improved supply chain efficiency, countries such as China, Japan and South Korea would gain faster access to European markets and lower transport costs for high-value exports, including electronics, machinery and automobiles. Therefore, their export competitiveness will increase, which will help stabilise or reduce the prices of traded industrial goods.

The opening of the Arctic routes could enhance the development of Russian ports along the Arctic coast. Russia could then offer cheaper energy and bulk commodities to Asia and Europe, thereby influencing prices in connected markets.

The flip side is: players in Southeast Asia, South Asia and Africa would be adversely affected, since Arctic routes bypass Southeast Asia and cargo may no longer transit through their ports. Some shipping services may also be reduced.

“If the Arctic routes are treated as a complement rather than a replacement for existing trade corridors, they can create a win-win situation by increasing the resilience and flexibility of global shipping networks,” Low added.

Rising geopolitical tensions put Greenland on centre stage

Due to the sanctions on Russia over recent years, controls along the usual southern route via the Suez Canal have been tightened, leading to the rising significance of the NSR. The threat of Houthi militants to shipping through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea further propels interest in the Arctic routes. Particularly interested are companies dealing with Russia and other European countries.

... Russia treats the NSR as strategic infrastructure, while the US emphasises freedom of navigation. China, calling itself a “near-Arctic state”, seeks access to shipping lanes, standards-setting influence and critical minerals. — Wong Meng Yew, Global Trade Advisory Leader, Deloitte Singapore and Southeast Asia

To control and monitor traffic on the NSR is, as described by ICS’s Oza, “a strategic advantage, currently limited to Russia and its trade partners”, but “the US and its allies also want to get a slice of the pie”. “It will be tough though,” he said, “as most of the NSR passes through Russia’s exclusive economic zone.”

Deloitte’s Wong paints the big picture thus: Russia treats the NSR as strategic infrastructure, while the US emphasises freedom of navigation. China, calling itself a “near-Arctic state”, seeks access to shipping lanes, standards-setting influence and critical minerals. As for Finland and Sweden, now firmly embedded in NATO, Arctic security is anchored within a broader transatlantic framework.

Meanwhile, the rapid melting of polar ice caps and increasing attention towards the NSR has highlighted the geopolitical significance of Greenland.

Greenland’s abundant resources exportable via Arctic routes

SMU’s Low noted that Greenland’s position at the ingress and egress of the North Atlantic allows control over access to Arctic air and sea approaches. Furthermore, the island is rich in rare-earth elements, uranium, iron, zinc and other strategic minerals, so the exports of these resources could reach European or Asian markets faster and cheaper via the shorter Arctic shipping routes.

Oza is concerned that, given the aggressive stand of the Trump administration towards Greenland, tensions may well escalate, especially between the US and Russia — even between the US and its European NATO allies. The situation is unprecedented.

Nevertheless, Low thinks the jostle over the Arctic is unlikely to reach the level of intensity historically seen in conflicts in the Middle East or over the Suez Canal. She believes that cooperative frameworks such as the Arctic Council, agreements on environmental standards, as well as regulated navigation rules can help manage tensions, balancing economic opportunities with environmental protection and strategic security. The combination of legal frameworks, technological monitoring and multilateral engagement makes the Arctic a more manageable and controlled zone of rivalry, as compared with highly contested chokepoints like the Suez Canal.

... the core containerised trade that sustains Singapore’s transhipment hub role will continue to rely primarily on the Suez-Malacca corridor and intra-Asia networks. — Assistant Professor Joyce Low, Lee Kong Chian School of Business, SMU

Unlikely to undercut Singapore’s hub status

So, how is the development of the NSR going to impact Singapore’s status and future as a maritime hub?

In Low’s opinion, any direct impact will be limited. That’s mainly because the route is not suitable for most container trade. Container shipping depends on year-round reliability, dense port networks and high service frequency. The Arctic routes, however, are highly seasonal, risky and lacking in supporting port infrastructure. As a result, they are likely to be used for bulk commodities and energy exports only.

“Therefore, the core containerised trade that sustains Singapore’s transhipment hub role will continue to rely primarily on the Suez-Malacca corridor and intra-Asia networks, ” she added.

Low also pointed out that Singapore’s importance today is driven more by intra-Asia trade, regional connectivity, maritime services and supply chain coordination than by Europe-Asia trade alone.

She said, “Singapore has evolved from a transit port into a comprehensive maritime and logistics ecosystem offering bunkering, ship management, finance, arbitration, digital logistics and regional headquarters functions. These roles cannot be replicated by Arctic ports.”

“On trade lanes, the Europe-Asia corridor matters, but Singapore’s role is not limited to that. Singapore is fundamentally a global transhipment and network hub, connecting intra-Asia, Asia-Europe and Asia-North America flows via carrier networks and alliance routing.” — Associate Professor Yuen Kum Fai, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, NTU

This ecosystem encompasses different aspects, such as: efficient customs clearance processes; seamless transhipment processes; continuous upgrading of port infrastructure; a complete maritime support ecosystem; advantaged management and coordination services; financial services; legal and dispute resolution services; connectivity and digitalisation services; a stable, secure and well-regulated environment; as well as sustainable development strategies (maritime decarbonisation).

NTU’s Yuen unpacks more of what’s going on: “On trade lanes, the Europe-Asia corridor matters, but Singapore’s role is not limited to that. Singapore is fundamentally a global transhipment and network hub, connecting intra-Asia, Asia-Europe and Asia-North America flows via carrier networks and alliance routing. Around 90% of Singapore’s container throughput is transhipment, which shows that the hub function is about connectivity and service quality rather than only local import/export demand.”

On the matter of using the NSR, most of the maritime companies interviewed claim it is not being considered for now.

Lars Kastrup, CEO of Pacific International Lines (PIL), explained to Lianhe Zaobao why his company is not moving in that direction: “Given the Arctic’s ecological sensitivity and the significant uncertainties involved in its long‑term sustainable navigability, we view developments in this region with caution. We recognise that the environmental trade‑offs are both substantial and uncertain, and as such, PIL has no intention to deploy our ships on the Arctic route. Our focus remains on advancing responsible and sustainable practices within our established global network.”

Arctic routes unable to replace Singapore given its diverse services

Shipping and logistics company Maersk’s spokesperson expressed a similar stance: “While the NSR may offer a shorter passage, we do not consider it a viable option for several reasons. The environmental risks are significant, and from an operational standpoint, there are considerable limitations regarding navigable time windows, infrastructure, vessel size, vessel type and safety in general. Also, we do not have any business activities in Russia.”

In its reply to Lianhe Zaobao, the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) stated: “Singapore monitors global shipping developments, including interest in Arctic routes such as the NSR.

“At present, the Arctic routes face seasonal constraints, which include harsh weather, thick ice, and limited supporting infrastructure. However, as temperatures rise, the Arctic routes could become passable year-round, potentially impacting some trade flows between Asia and Europe.

“As global routing patterns continue to evolve, MPA will work closely with partners and stakeholders to strengthen the Port of Singapore’s connectivity, productivity, service offerings, and competitiveness, to meet the long-term needs of international shipping and global supply chains.”

While the prospects of the NSR are predicated on geographical advantage, Singapore’s position as a maritime hub is — as SMU’s Low puts it — underpinned by “a comprehensive, multi-dimensional strategy that goes far beyond geographical advantage”.

Singapore’s competitive edge lies not in physical distance, but in its platform economy.

She explained the optimistic outlook further: “Singapore has transformed from a location-based hub into a capability-based maritime ecosystem. This ensures that even as trade routes evolve, Singapore’s maritime hub status remains resilient, adaptive and future-proof.

“Geography opened the door for Singapore, but its political stability and good governance, coupled with intelligent and massive investment, contributes to the rise of the Singapore port and its maritime industry.”

All in all, it can be said that Singapore’s competitive edge lies not in physical distance, but in its platform economy.

Tuas mega port to consolidate cargo flows from different locations

According to Deloitte’s Wong, the Tuas mega port embodies precisely the strategy described above. When fully completed, Tuas can handle up to 65 million TEUs, nearly double the present capacity. It is designed as a fully automated, low-emissions, digitally integrated port capable of consolidating cargo flows regardless of where ships originate.

“Tuas is not a defensive response to Arctic routes. It is an offensive investment in scale, efficiency and resilience,” he said.

In addition, Singapore is making investments overseas too. As noted by NUS’s Goh, port operator PSA and other companies also invest in maritime infrastructure that can create linkages to Singapore. The Chongqing Connectivity Initiative is one example. This enables Singapore to continue to play a role in the global maritime and transportation network.

Even though geography may open doors of opportunity, at the end of the day it is institutions, investment and trust that determine who remains indispensable. In the future that Deloitte’s Wong believes in, “Singapore’s relevance is not diminishing, it is evolving.”

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “悉看大势:北海航线虽破冰缩程 想绕过新加坡还太早”.