Trump’s Maduro raid leaves Xi with no easy options

The capture of Venezuela’s president exposes Beijing’s intelligence failure and forces Xi Jinping to choose between confrontation, restraint or strategic retreat in the western hemisphere. RSIS senior fellow Drew Thompson examines US actions and China’s reading of the situation.

The dramatic and unexpected capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro by the US on 3 January is a watershed moment that will affect China’s influence in the western hemisphere and potentially the tenor of US-China competition.

Trump Corollary is not just rhetoric

The National Security Strategy released in December 2025 announced that the US will “reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine” to protect the homeland and deny adversaries from using the western hemisphere to threaten the US, describing the new approach as the “Trump Corollary”.

Beijing was caught by surprise on 3 January.

The US military buildup was initially a show of force to intimidate Maduro to stop the flow of narcotics through the country or entice him to step down and leave the country. When incremental escalation and pressure failed to change his behaviour, the Trump administration took action to remove him. Following his capture, Secretary of State Marco Rubio declared: “This is the western hemisphere. This is where we live — and we’re not going to allow the western hemisphere to be a base of operation for adversaries, competitors, and rivals of the United States.”

Operation “Absolute Resolve” should remove any doubts about the credibility of the Trump Administration’s will to defend the hemisphere against adversaries.

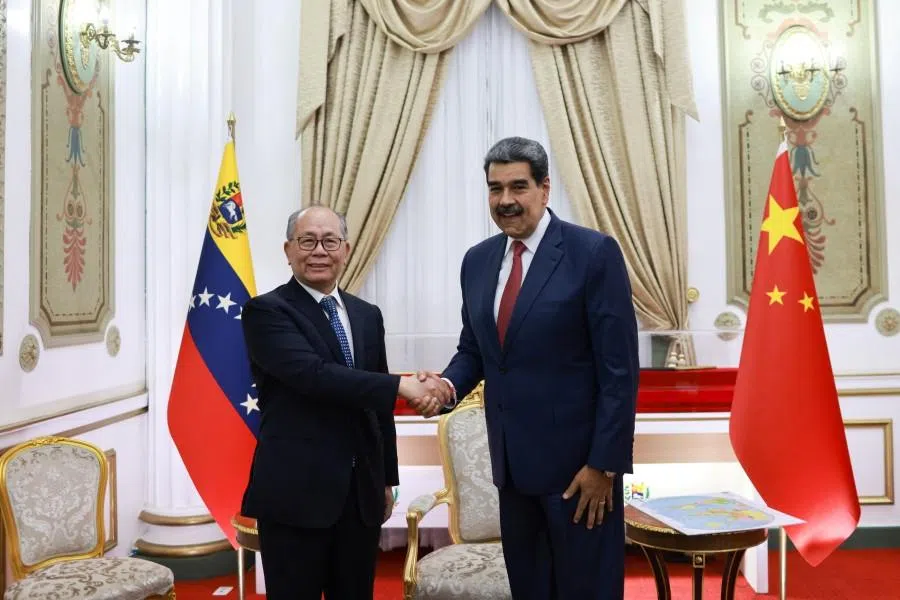

China underestimated Trump and his resolve

Beijing was caught by surprise on 3 January. Despite the military buildup, threats and missed deadlines, Qiu Xiaoqi, Beijing’s special envoy for Latin American affairs, met with Maduro hours before the intervention, discussing their all-weather relationship and bilateral projects, exchanging gifts in a business-as-usual diplomatic exchange with no indication there was concern about impending US military action. China’s official media was muted in the immediate aftermath of the strike, indicating that time was needed for an internal political assessment process to determine how to respond.

Despite strategic and operational indications and warnings of a military action, there was a failure in China’s intelligence cycle. The major failure was analytical. Beijing miscalculated President Trump’s resolve to enforce the Trump Corollary.

China’s future access and influence in Latin America and the Caribbean

The Venezuela intervention might prompt some soul searching in Beijing about the implications for China’s foreign policy, and the US-China relationship going forward.

It is clear that Washington will actively limit Chinese (and Russian) influence in the region as well as pressure regimes that are hostile to Washington. While there may be some tolerance for normal trade and investment between China and the Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) countries, there should be little doubt that Washington will push back against PRC investments in strategic assets, including mines and dual-use facilities such as ports. Chinese security cooperation, arms sales and military presence will be discouraged or prevented if deterrence fails.

The capture of Maduro sends a clear message to LAC countries about the costs of anti-American sentiment and the risks of granting China too much economic or military access.

China’s interests in Latin America are primarily political and economic, but there are security aspects as well. LAC is a key component of the so-called Global South, which China seeks to lead and represent in international forums. About 20 Latin American and Caribbean countries are members of the Belt and Road, seven are members of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Politically, the region includes several of Beijing’s ideological allies including Cuba, one of the few remaining communist regimes, as well as several leftist anti-American regimes.

China is a major investor in infrastructure, notably transportation, technology and resource extraction. China’s trade with LAC countries in 2024 reached US$476 billion fuelled by China’s demand for raw materials and the region’s need for manufactured goods.

The capture of Maduro sends a clear message to LAC countries about the costs of anti-American sentiment and the risks of granting China too much economic or military access. China’s military presence and Cuba’s longstanding hostility towards Washington make it a likely future hotspot and benchmark for Washington’s enforcement of the Trump Corollary. The US has accused Cuba of operating several signals intelligence sites backed by China. Cuba’s air defence system is unable to defend its airspace from US strikes and operations, making it vulnerable to limited military operations just as Venezuela was.

Xi Jinping faces hard choices in the western hemisphere

The intervention in Venezuela itself is not likely to affect the overall trajectory of US-China relations but resolute enforcement of the Trump Corollary creates new competitive dynamics and will affect how Beijing perceives Washington. The 3 January intervention establishes that Trump is decisive, has a high tolerance for risk, and the will to execute an articulated strategy. It also affirms that Washington sees competition with China as global, not limited to the Indo-Pacific.

Will Xi Jinping directly challenge Washington and provide credible security guarantees and military assistance to anti-American ideological allies in the region? Will China seek to establish military bases in Latin America beyond signals intelligence sites in Cuba?

How Beijing will respond is unknown. Xi Jinping must decide if, or how much he will push back against US assertions of dominance in the western hemisphere. China has historically avoided entanglements, foreign interventions and making commitments to defend partners. The Trump Corollary forces a strategic choice on Beijing.

Will Xi Jinping directly challenge Washington and provide credible security guarantees and military assistance to anti-American ideological allies in the region? Will China seek to establish military bases in Latin America beyond signals intelligence sites in Cuba? This would be costly for China due to the certainty of an American response, and the limited ability of China’s partners to fund their own defence, making expanded security assistance strategic donations rather than financed commercial transactions.

This expanded, commitment-centric, credibility-laden approach to relationships is contrary to Chinese foreign policy and would require a dramatic shift in Beijing’s approach. Such a shift might be unpopular with the Chinese public, who would prefer state resources be spent at home. China’s population has also been conditioned to abhor imperialism and foreign entanglements of the sort the US is prone to, as well as those which contributed to the demise of the Soviet Union, making such a policy choice unpalatable.

Xi could regardless decide that the prospect of being pushed out of the western hemisphere, while Beijing’s ideological allies in the region fall like dominos threatens the party’s legitimacy and survival. The prospect for cold war-style proxy conflicts in Latin America is therefore potentially on the table if Xi Jinping determines it is necessary to maintain the party’s credibility and security by propping up LAC allies.

Alternatively, Xi could decide the stakes in LAC are not worth it, and there is more to be gained by fostering a stable relationship with the US while focusing diplomacy and competitive engagement on China’s periphery, where Beijing’s advantages and core interests lie.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)