The Greenland myth: Why invasion talk misleads

The current conversation about “occupying Greenland” is an imprecise framing of the issue. The more consequential contest is about alliance governance, early warning and sensing, long-horizon Arctic connectivity, and the rules that shape future resource development, says US academic Hong Nong.

US President Donald Trump’s remark that Russia or China could “occupy Greenland” has pulled the territory back into the centre of global geopolitics. The phrase is rhetorically potent but strategically imprecise. It frames Greenland as an object to be seized, when the more consequential contest is about alliance governance, early warning and sensing, long-horizon Arctic connectivity, and the rules that shape future resource development.

A useful starting point is to separate a low-probability “occupation” scenario from the higher-probability dynamics already visible: influence, positioning and institutional choices. Greenland is unlikely to be occupied in any conventional sense. Yet it is strategically important enough that Washington, Moscow and Beijing each have distinct reasons to care about how Greenland is governed, defended and connected to wider Arctic and North Atlantic security. In latest developments, Trump has declared that he would impose increasing tariffs on European allies until the US is allowed to buy Greenland.

What Greenland is, and is not

Greenland is self-governing, but it remains part of the Kingdom of Denmark, with extensive domestic autonomy and a formal pathway for Greenlanders to determine their future status. In practice, Denmark retains core responsibilities for defence and foreign affairs, while Greenland’s institutions exercise legislative and executive authority in devolved areas.

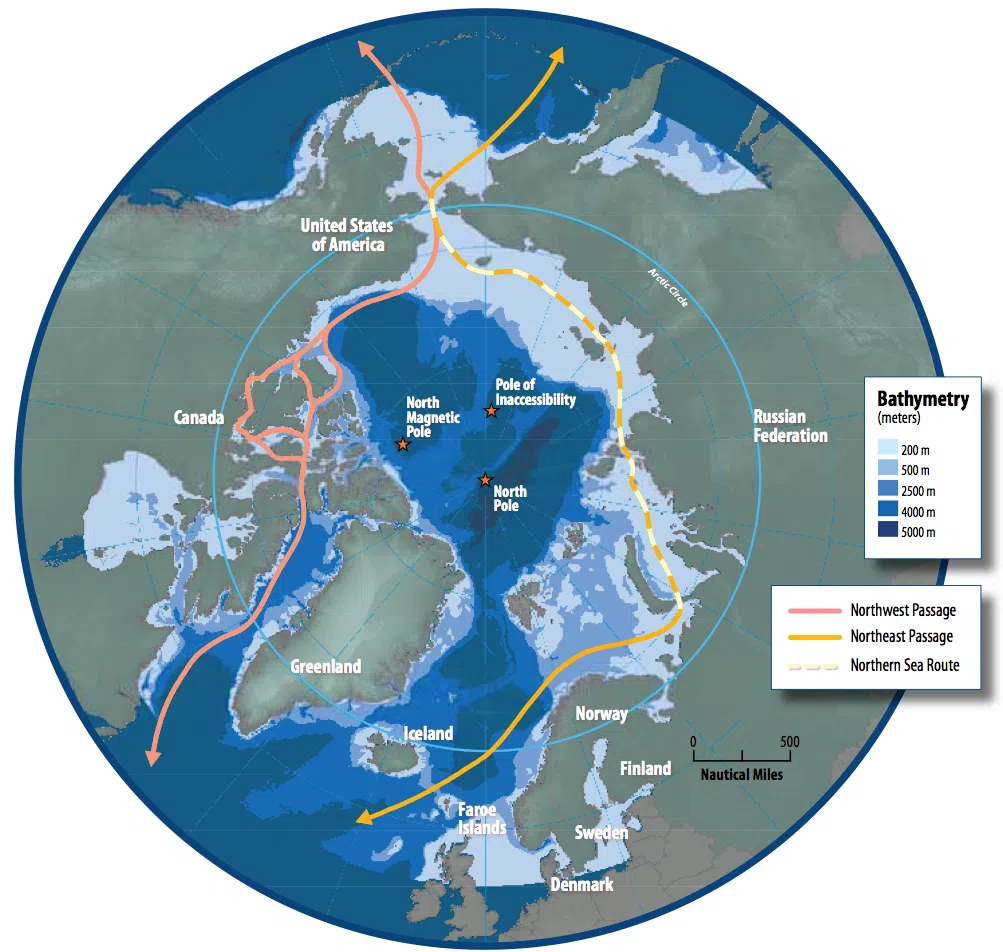

Greenland is not on the NSR [Northern Sea Route], which reduces the plausibility of Greenland as a core Russian “shipping prize”. Russia’s Greenland-related interests are better understood as indirect.

Constitutional and alliance context matters. Denmark is a NATO ally, and in high-level talks in Washington, including the 14 January meeting involving Vice-President JD Vance, Danish and Greenlandic officials reiterated that Greenland is “not for sale”, while European partners affirmed support for Denmark and Greenland’s sovereignty. Whatever strategic competition exists around Greenland therefore, unfolds under alliance politics, escalation risks and legal constraints, conditions that make literal “occupation” a poor analytic shorthand.

Russia and China: interest without conquest

Russia’s most concrete Arctic priority is the Northern Sea Route (NSR), a shipping corridor along Russia’s Arctic coastline linking the Euro-Arctic to the Pacific. Greenland is not on the NSR, which reduces the plausibility of Greenland as a core Russian “shipping prize”.

Russia’s Greenland-related interests are better understood as indirect. They derive less from trade routes than from the wider NATO-Russia rivalry and the military balance between the Arctic and the North Atlantic. In that context, Greenland matters because of its location: it sits near the air and sea corridors that connect the High North to the North Atlantic, and it affects what can be monitored — air and naval movements — as well as the vulnerability of infrastructure such as undersea cables. Seen this way, Moscow’s stake is about visibility and positioning in the broader region, not about taking Greenland itself.

Even “economic influence” has limits. In Greenland, proposals involving Chinese capital or research partnerships have tended to trigger public debate and regulatory scrutiny...

China, meanwhile, is not an Arctic littoral state. Its ability to shape outcomes in Greenland therefore runs primarily through commercial, scientific and diplomatic channels rather than any plausible bid for territorial control. That is precisely why “occupation” rhetoric is analytically and politically unhelpful: it conflates influence seeking with invasion, and it sits uneasily with Beijing’s repeated public emphasis on sovereignty and non-interference.

Even “economic influence” has limits. In Greenland, proposals involving Chinese capital or research partnerships have tended to trigger public debate and regulatory scrutiny, and it would also be shaped by Denmark’s role in foreign and security policy and by wider NATO sensitivities. In practice, the relevant tools are routine — investment bids, research partnerships, standards setting, and longer-term supply-chain planning — and each can be slowed or blocked by decision makers at multiple levels.

Shipping routes: peripheral, but not irrelevant

Shipping is often where discussions get tangled. Greenland is not on the NSR, which runs along Russia’s Arctic coast. The Northwest Passage (NWP), by contrast, is a set of routes through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago linking the Atlantic and Pacific, with approaches in the wider region where Greenland sits near the North Atlantic gateway.

Even here, caution is warranted. The NWP is not a single, stable shipping highway. Arctic shipping remains constrained by ice variability, limited infrastructure, insurance and safety requirements, and search-and-rescue capacity. For the foreseeable future, Arctic routes will supplement rather than replace established global sea lanes. In that sense, Greenland’s shipping relevance is better understood as optionality: it could become more important as a monitoring or support node if Arctic traffic grows, but it does not “control” Arctic trade.

Greenland’s near-term weight is primarily security-related: early warning, missile defense support, space and maritime domain awareness, and the linkage between the North Atlantic and the Arctic.

Greenland’s real strategic value: early warning and alliance management

If shipping is a long-horizon consideration, Greenland’s near-term weight is primarily security-related: early warning, missile defense support, space and maritime domain awareness, and the linkage between the North Atlantic and the Arctic. This is why the US already holds substantial security equities in Greenland through longstanding defence arrangements — and why Washington’s effective leverage does not depend on any change in sovereignty.

US defence and Space Force descriptions of Pituffik Space Base underline its role in missile warning, missile defence and space surveillance, supported by radar and tracking infrastructure. This sensor architecture is the practical core of Greenland’s significance: it helps underpin deterrence and defense in a changing Arctic operating environment.

Alliance governance is therefore central. Denmark and Greenland have consistently pushed back against sovereignty-based claims while remaining open to stronger security cooperation within allied frameworks. Any reinforcement is channelled through NATO-linked mechanisms, such as exercises, rotations and coordination, rather than through arrangements that could blur sovereignty questions. Denmark’s defence communications likewise emphasise an expanded presence and continued activities in Greenland in close cooperation with allies, including planning assumptions for 2026.

In alliance politics, tone and framing are not cosmetic. They shape trust, domestic legitimacy and the political bandwidth for cooperation. When the debate is cast in sovereignty-charged terms, it risks imposing collateral costs on the very defence relationships and operational arrangements that already function effectively.

Resources and the politics of access

Greenland is often described as mineral-rich, but the real question is not who can “grab” it. It is who can make projects viable under politically acceptable, legally sound and environmentally credible conditions. This is where external debates can go off track.

Framing Greenland as a stockpile to be “secured” invites backlash, politicises permitting and spooks investors by turning projects into sovereignty contests. A more durable approach focuses on mutual benefit and institutions — clear rules, strong safeguards, workable financing and transparency — so alignment and access can be achieved with far less friction.

For Washington, the near-term risk is not an imminent “occupation” by Russia or China. It is that sovereignty politics spills into day-to-day defence cooperation and makes practical coordination harder to sustain.

For China, the relevant leverage is primarily commercial rather than military; for the US and European actors, the challenge is mobilising investment and capacity-building without triggering the very politicisation that slows projects down. Russia fits this picture differently: its stake is less about underwriting Greenland’s mining projects than about how resource-linked infrastructure and external engagement might shift the security and signalling balance across the Arctic-North Atlantic — reinforcing why “resources” matter politically even when they do not translate into a plausible territorial endgame.

Why rhetoric matters more than ‘occupation’ scenarios

Even if no formal policy change follows, repeated talk of “control” reshapes incentives. It nudges European capitals to treat Greenland as a test of sovereignty and alliance cohesion, rather than a domain of routine coordination. It also increases pressure on Greenlandic leaders to signal autonomy and protect domestic legitimacy by emphasising self-determination — raising the political temperature even when day-to-day security cooperation remains practical and mutually beneficial.

For Washington, the near-term risk is not an imminent “occupation” by Russia or China. It is that sovereignty politics spills into day-to-day defence cooperation and makes practical coordination harder to sustain. Because alliances underpin US influence in both the Arctic and the Indo-Pacific, avoidable strain in the North Atlantic can carry reputational costs and complicate coordination elsewhere — especially where unity and credibility are meant to be assets.

Greenland is unlikely to be occupied by Russia or China...

Greenland is unlikely to be occupied by Russia or China; neither has the incentive to pursue such an outcome, and political, legal and escalation constraints make it highly implausible. The more meaningful contest is over how Arctic power is exercised: through institutions or coercion, coordination or confrontation.

If the Arctic is to remain stable, the task is not to prevent imaginary invasions, but to manage competition without eroding the institutional guardrails — rules, agreements and practical coordination mechanisms — that help keep security sustainable. In that sense, Greenland is less a battlefield than a test of strategic maturity.