Is Japan’s military revival a step forward or a step too far?

In recent times, Tokyo’s military transformation has begun to look less like a speculative trajectory and more like a rolling deployment — in budgets, doctrine and hardware. Commentator Imran Khalid shares his thoughts on the implications.

It has taken eight decades, but Japan’s postwar pacifist facade is shedding its camouflage. Since the dawn of 2025, Tokyo’s military transformation has begun to look less like a speculative trajectory and more like a rolling deployment — in budgets, doctrine and hardware.

Where earlier iterations of Japan’s “normalisation” were encased in cautious language and political hedging, the latest developments indicate a more unambiguous course: one that not only stretches the limits of Article 9 of the Japanese constitution, but attempts to redraw regional defence assumptions altogether.

Militarisation with global implications

With a record 8.7 trillion yen (S$55 billion) defence budget — the largest in Japan’s postwar history — Tokyo has taken a decisive step toward operationalising what it once only tentatively whispered: self-sufficiency in defence production, outward military engagement and embeddedness in Western strategic frameworks.

Gone are the days when the Japanese Self-Defence Forces (JSDF) operated under a doctrine of domestic containment. They are now carrying out logistics operations in the Philippines, jointly developing missile systems with Italy and the UK, and displaying railguns and warships at international arms expos. Tokyo’s challenge now is to convince not just allies, but neighbours — that a more capable Japan need not be a more dangerous one.

What was once a policy of military minimalism is rapidly morphing into militarisation with global implications — and Tokyo is not disguising it.

Tokyo is not only expanding its defence-industrial base but inserting itself into the very circuits of NATO-affiliated arms production.

A key inflexion point was Japan’s participation in the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) with Britain and Italy, agreed in 2022, to deliver a next-generation fighter aircraft by 2035. While plans have been stalled, the EU recently approved the formation of a joint venture company for the GCAP.

Beyond the technical marvels of next-generation missiles and AI-enabled fighters, this initiative carries heavy political freight: it is the first concrete manifestation of Japan’s revised arms export policy, amended in late 2023 to permit the overseas sale of lethal weapon systems co-developed with foreign partners.

This is not merely about technology. It is about normalisation — not just in narrative, but in practice.

Through GCAP, Tokyo is not only expanding its defence-industrial base but inserting itself into the very circuits of NATO-affiliated arms production. That it has chosen the UK — a core NATO member with post-Brexit defence ambitions — as a lead partner underscores Japan’s desire to bind itself more tightly into Western security architectures. The move complements recent staff-level military dialogues with NATO, a body that once had only notional relevance to East Asian security.

That, too, has changed.

Equally telling is Japan’s recent surge of engagement in Southeast Asia, specifically the Philippines — a country that has become a proxy theatre for regional balancing against China. In May, Japan signed a logistics cooperation agreement with Manila, paving the way for Japanese forces to store supplies and operate more freely in Philippine territory. For a country once allergic to power projection beyond its immediate periphery, this marks a historic shift.

... its neighbours remember a different Japan — one whose “defence” posture once rationalised aggression across the Pacific.

Normalisation across political mainstream

Strategically, Tokyo appears to be acting on a doctrine of lateral deterrence. Japan is repositioning itself to contribute to the regional security matrix in a manner that is qualitatively different from its previous “checkbook diplomacy” of the 1990s. Now, it is ships and soldiers, not just yen and statements. The message is unambiguous: the JSDF is no longer confined to the home islands.

Domestically, the pace of transformation has quickened. The Diet is currently deliberating legislation that would further dilute Article 9’s restrictions, especially regarding collective self-defence. While Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba has styled these moves as necessary adaptations to a changing regional environment, they reflect a political consensus that has been years — if not decades — in the making.

Indeed, what was once the preserve of right-wing fringes in Japan — the revisionist longing for military parity and international assertiveness — is increasingly normalised across the political mainstream. Even opposition parties have largely refrained from mobilising mass opposition, signalling either strategic exhaustion or ideological acquiescence.

The unease is understandable. Japan may insist it is only bolstering its defences, but its neighbours remember a different Japan — one whose “defence” posture once rationalised aggression across the Pacific. For them, every legislative tweak in Tokyo echoes not just in parliament halls, but across gravesites and textbooks.

Mixed reactions from Japan’s neighbours

Yet Japan’s military resurgence does not provoke universal suspicion. Recent opinion surveys reveal a more nuanced regional response — especially among Southeast Asians and Taiwanese. In Taiwan, a 2024 public opinion poll by the Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association found that 76% of respondents view Japan favourably, a notable rise from previous years. Among those aged 50-80, trust in Japan has grown significantly, even as confidence in the US and China has declined.

... for some in the region, Japan’s assertiveness is not necessarily a threat, but a welcome counterbalance to the more destabilising behaviours of larger powers like China or the US.

Similarly, the 2025 State of Southeast Asia survey indicates rising trust in Japan among ASEAN elites, with 66.8% now viewing Tokyo as a reliable strategic partner. Japan, alongside the EU, is seen as a preferred middle-power hedge — especially due to its consistent advocacy of international law.

These sentiments suggest that for some in the region, Japan’s assertiveness is not necessarily a threat, but a welcome counterbalance to the more destabilising behaviours of larger powers like China or the US.

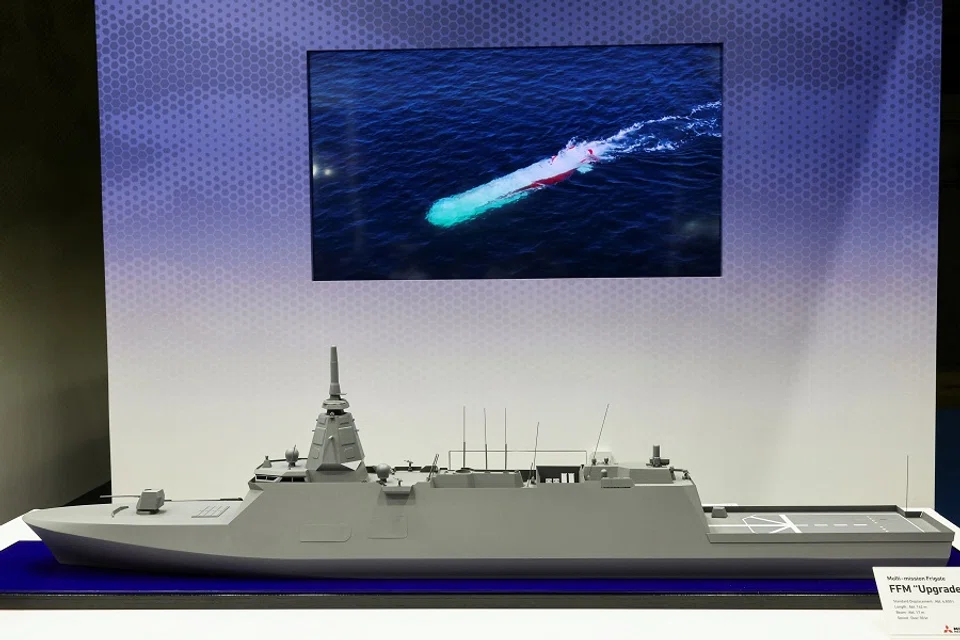

There’s also the economic dimension to consider. Japan’s increased presence in international defense exhibitions — most recently DSEI Japan 2025 in May — is not just symbolic. Tokyo is signalling its intent to become a competitive player in the global arms market. The same country that, until a decade ago, maintained a near-total ban on weapons exports, is now marketing railguns, stealth technologies and naval platforms to international buyers.

This commercial ambition dovetails with strategic goals. Defence exports not only fund domestic innovation but entrench diplomatic relationships. Arms, after all, are not merely tools of warfare — they are tokens of alliance and levers of influence.

And Japan seems ready to use them as both.

Ships are being launched, laws are being rewritten, partnerships are being inked. The old taboos are not merely fading; they are being formally retired.

US-Japan alliance factor

Underlying this entire evolution is the recalibration of the US-Japan alliance. Far from eroding Washington’s role, Tokyo’s militarisation is being nurtured within it. The Trump administration has warmly welcomed Japan’s moves, viewing them as a much-needed offset to Chinese military dominance in the Indo-Pacific.

But this growing symmetry masks a deeper asymmetry. Japan is no longer a mere client in the American security architecture — it is becoming a co-architect. Through joint exercises, intelligence-sharing and increasingly interoperable platforms, the JSDF is positioning itself not just as a regional force, but as an Indo-Pacific stakeholder.

If the postwar American order rested on Japan’s strategic abstention, the emerging order will rely on its strategic participation. The shift is not only permitted — it is now expected.

What we are witnessing in 2025 is not just an evolution, but an execution. Japan’s long-debated military revival is no longer aspirational or conceptual — it is material. Ships are being launched, laws are being rewritten, partnerships are being inked. The old taboos are not merely fading; they are being formally retired.

Still, the question remains: at what cost?

Japan may argue that its security policies are rooted in necessity, not nostalgia. But as military exports grow, overseas deployments increase and constitutional debates continue, Tokyo’s actions may increasingly speak louder than its reassurances.

In a region still haunted by 20th-century scars, the burden of trust remains heavy. Strategic ambition without strategic empathy risks reawakening the very insecurities Japan seeks to deter. Tokyo’s challenge now is to convince not just allies, but neighbours — that a more capable Japan need not be a more dangerous one.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)