Middle powers and international law: A bulwark against Thucydides Trap

Academic Chris Alden and researcher Kenddrick Chan assert that even as great power rivalry intensifies, middle powers have agency to navigate their way with the help of international law and group coalitions.

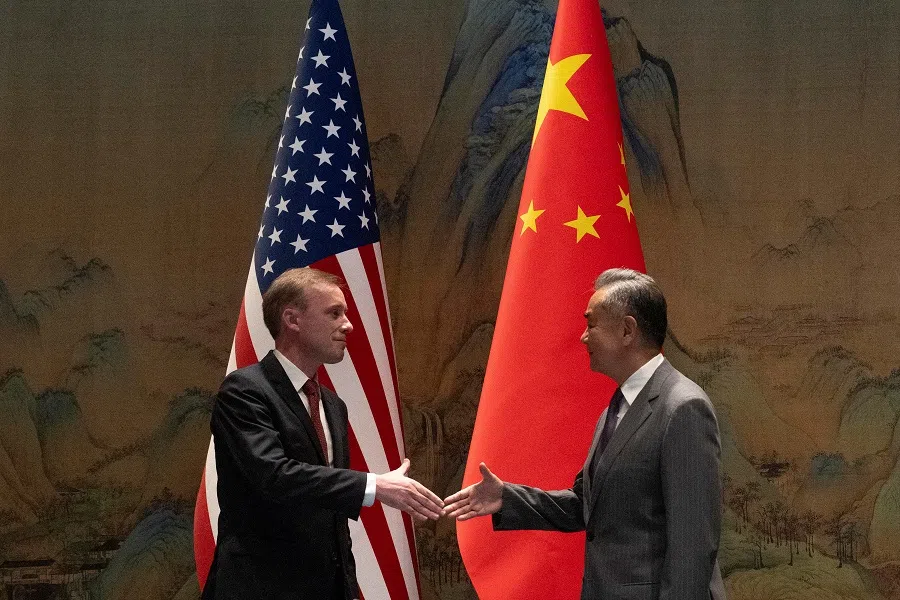

Within policy-making circles today, there is growing concern that deteriorating tensions between the US and China constitute the “Thucydides Trap” — the idea that a power transition between a dominant global power (i.e. the US) and a rising one (i.e. China) will most likely lead to armed conflict and potentially spiral into a broader regional or even global war. This concern is arguably justified.

Despite occasional statements from both sides emphasising the need to improve ties, much evidence suggests that US-China relations are unlikely to become cordial in the near future. Furthermore, as ongoing conflicts and tensions in other parts of the globe illustrate, states are increasingly predisposed to using military force (or variants thereof) as their primary means of achieving foreign policy objectives. In other words, the use of force as a mechanism for dispute resolution is gradually becoming less taboo than in previous years.

Best available option

Yet as power transition theories also demonstrate, a rising China in competition with the US does not necessarily imply an inevitable descent into war. Nor is the use of military force destined to become the first option in the foreign policy toolkit of statesmen. In the conduct of international politics, there remains significant space for international law and its associated norms and mechanisms to collectively prevent a world defined solely by power politics.

Admittedly, international law has been criticised for its limited ability to deliver intended outcomes and meaningfully shape state preferences and behaviour. This critique often extends to the broader role of liberal ideals as a guiding framework for international politics.

While such criticisms are valid, they underscore the need for stronger, more enforceable international law rather than its dismissal. The raison d’être of international law remains: despite its imperfections, international law — and the various instruments and fora through which it operates — represents the best available option for peacefully resolving disputes in the absence of a truly neutral “global policeman”.

... emerging middle powers — such as Indonesia, Brazil, Turkey and South Africa — have increasingly utilised international law and mediation as tools to resolve disputes, particularly in the context of contemporary great power competition.

International law as foundation for mediating

Middle powers, by virtue of their position within the international system, play a distinctive role in global affairs. Unlike great powers, which are more easily identifiable, there is no singular criterion for determining whether a state has achieved “middle power” status. However, middle powers can often be recognised through their foreign policies.

Traditional middle powers, such as Canada and Australia, have long been proponents of liberal norms and active promoters of compliance with international law, particularly in the post-Cold War era. Their commitment to these values has earned them recognition from emerging powers and smaller states.

Similarly, emerging middle powers — such as Indonesia, Brazil, Turkey and South Africa — have increasingly utilised international law and mediation as tools to resolve disputes, particularly in the context of contemporary great power competition.

For instance, Indonesia, though not a claimant state in the South China Sea, has actively promoted the use of international law — specifically, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) — as a framework for resolving tensions among claimant states.

In another case, Brazil, in partnership with Turkey, brokered a nuclear fuel swap deal with Iran in May 2010 in order to reduce tensions over its nuclear programme. Although the deal was ultimately rejected by Western powers, it demonstrated the willingness and ability of both Brazil and Turkey to use international law as the foundation for mediating a highly sensitive issue involving Iran and the permanent members of the UN Security Council.

Forming coalitions

A number of efforts have also been pursued by middle powers in coalition with emerging powers and smaller states to kick start negotiations to end Russia’s war with Ukraine. These include shuttle diplomacy efforts undertaken by Indonesian President Jokowi Widodo ahead of the G20 summit meeting in 2023 and a subsequent plan promoted by then Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto in multilateral settings such as ASEAN and the G7.

Seven African states, led by South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, had also attempted to encourage negotiations, meeting both leaders involved in the conflict in 2023. The likes of Turkey also played a pivotal role in brokering the Black Sea Grain Initiative between Russia and Ukraine in July 2022, under the auspices of the UN, which allowed for the safe passage of Ukrainian grain exports during the conflict in an effort to stabilise global food prices and alleviate concerns over potential famines in developing countries.

These examples, while not exhaustive, underscore the crucial role that middle powers can and do play in driving diplomacy and legal mediation efforts, even amid periods of intense great power competition.

The formation of a coalition of middle powers in support of international law and its institutional manifestations, such as the International Court of Justice (ICJ) or the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), would represent a noteworthy stance against the drift towards great power conflict.

A middle power coalition could therefore serve as a counterweight to geopolitical risks generated by great power rivalry, offering alternative approaches to dispute resolution through legal mechanisms and anchored in international law.

As great power tensions increasingly risk undermining multilateralism and international law, a coalition of traditional and emerging middle powers dedicated to upholding international law would reaffirm the importance of international law in global governance. Middle powers, with their reputation for diplomatic agility, can be well-suited to mediate conflicts where great powers may be directly involved or have an interest in.

A middle power coalition could therefore serve as a counterweight to geopolitical risks generated by great power rivalry, offering alternative approaches to dispute resolution through legal mechanisms and anchored in international law. Recent developments suggest that such coalitions are beginning to take shape around key global issues. The likes of Canada, Mexico, Norway, Sweden and others have been instrumental in putting weight behind efforts by the Alliance for Multilateralism to reinforce the rules-based international order and counteract the growing trend of unilateralism.

The coalition has called for strengthening of the World Health Organization during the Covid-19 pandemic and continues to actively advocate for international cooperation in other areas of global governance, such as on climate change and the use of autonomous weapons. By collectively endorsing international law and supporting international mediation efforts, such a grouping would signal their commitment to preserving international stability and mitigating the dangers posed by escalating tensions and great power competition.

Acting through the United Nations

Governments around the world, acting through the United Nations, should support this initiative. Having the backing of the UN would add further weight to such an initiative, thereby “bestowing” upon both traditional and emerging middle powers their responsibilities as key stakeholders in promoting global stability. The relationship is also mutually beneficial — it would reaffirm the importance of international law, the need to resolve disputes through peaceful means, and the continued relevance of the UN and its associated organs.

The collective commitment of middle powers to upholding international law and mediation as tools of diplomacy is not only a bulwark against the dangers associated with great power conflict but an ongoing reminder that international peace and stability is ultimately a shared responsibility of all states.

The time for middle powers to assert their influence is now. By being proactive stewards of global governance and advocates of international law, middle powers can provide the crucial leadership needed to steer the international system away from dispute resolutions based on military force and towards a rules-based international order. If done correctly, it helps to ensure that the Thucydides Trap remains a historical lesson, instead of an inevitable future.