No troops, no demands: China’s new appeal in a war-weary world

China’s limited engagement in the Iran-Israel conflict has not made it irrelevant in the Middle East. On the contrary, it has enhanced its appeal, especially among countries seeking partners beyond traditional power politics, says Middle East Institute-NUS research fellow Jing Lin.

In the recent conflict between Israel and Iran, much of the global attention has been focused on how major powers responded, particularly the US and China. The US showcased its military capability, reaffirmed its commitment to allies and underscored its capacity to shape outcomes in a volatile region, through a dramatic, high-stakes show of force.

China, by contrast, remained restrained and measured — often interpreted as passive or self-interested. Beyond diplomatic rhetoric condemning violence and calling for de-escalation, Beijing appeared to exert little practical influence over the course of events.

However, a curious dynamic has emerged, not on the battlefield, but on the global stage. China’s limited engagement has not made it irrelevant in the Middle East; on the contrary, it has enhanced its appeal, especially among countries seeking partners beyond traditional power politics.

Recent events in Tianjin and Beijing — the World Economic Forum’s Summer Davos and the 13th World Peace Forum jointly organised by Tsinghua University and the Chinese People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs — have become subtle stages for China to present its distinct worldview: one that resists short-term victories in favor of long-term transformation.

China takes the long view

China does not view the world in terms of short-term wins and losses. Instead, it advocates for long-term peace and stability, especially in regions like the Middle East where external power interventions have historically worsened conflicts rather than resolved them.

China’s aspiration is not to become a global policeman. In fact, Beijing fundamentally rejects the notion that any one great power should assume such a role. Mediation and conflict resolution, in China’s view, should be led by the United Nations, not unilaterally by hegemonic states.

If China were to insert itself deeply into the military or security dynamics of the Middle East, it would contradict the very principles it has long championed: non-intervention, peaceful development and a multilateral international order. It would also risk undermining the carefully cultivated image China has projected, as a stable, non-aligned power that prioritises economic cooperation and development over geopolitical rivalry.

Against this backdrop, China recorded a significant increase in cross-border capital inflows in May 2025, with more than US$33 billion entering its markets — almost double the figure from the previous month.

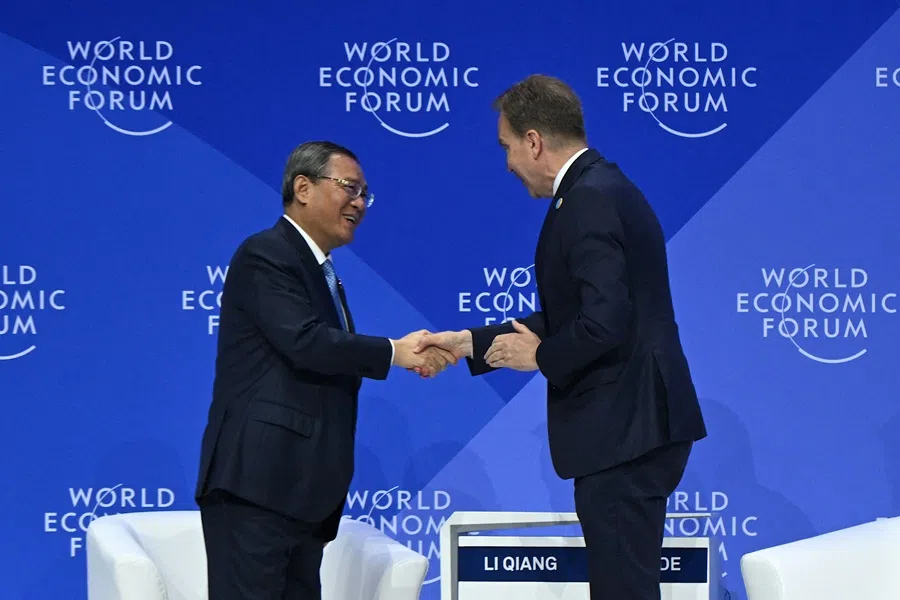

China’s focus is on ensuring a peaceful environment conducive to development and the secure flow of resources, essentials for both domestic growth and global stability. This strategic posture was highlighted during the World Economic Forum’s 16th Annual Meeting of the New Champions in Tianjin on 24 June.

Chinese Premier Li Qiang reaffirmed China’s commitment to global economic cooperation, openness and multilateralism. He called for stable supply chains and warned against the fragmentation of global systems, an indirect criticism of geopolitical confrontation and economic decoupling.

The forum drew a record post-pandemic attendance, including around 120 participants from the Middle East and North Africa, twice as many as last year. While the forum’s main focus was economic, the rapid escalation of the Israel-Iran conflict temporarily eclipsed longstanding concerns such as trade wars, tariffs and inflation. According to WEF President Borge Brende, the world is facing “the most complex geopolitical and geo-economic backdrop in decades”.

Against this backdrop, China recorded a significant increase in cross-border capital inflows in May 2025, with more than US$33 billion entering its markets — almost double the figure from the previous month. This surge of investment is believed to come from Gulf countries that are increasingly unwilling to put all their eggs in one basket, seeking stable partners in fast-growing Asian markets.

Indeed, the global south increasingly views China not as a rival to the US, but as a counterweight to a model of crisis management rooted in militarisation and regime change.

China model marked by what it does not do

In a world increasingly fatigued by endless conflicts and great-power rivalries, China’s “long-term stability” approach is gaining resonance, particularly across the global south. Indeed, the global south increasingly views China not as a rival to the US, but as a counterweight to a model of crisis management rooted in militarisation and regime change.

To many countries across Asia, Africa and the Middle East, China’s model is appealing precisely because it does not come with troops, weapons or conditionality. Its credibility stems from what it does not do. It does not interfere in domestic politics. It does not seek to reshape governments through force. And it does not demand alignment in ideological terms. For the global south, still bearing the scars of foreign intervention, this model offers breathing space.

The message was even clearer at the 13th World Peace Forum hosted by Tsinghua University from 2-4 July. With over 1,200 attendees from 86 countries and regions, including many from the global south, the forum focused on discussing global peace and conflict resolution. China’s Vice-President Han Zheng proposed strengthening multilateralism through historical reflection, global solidarity, open cooperation and shared modernisation, aimed at safeguarding the post-war international order and promoting inclusive development.

Less power broking, more principles

At the press briefing ahead of the forum, Professor Yan Xuetong, director of The Institute of International Studies, Tsinghua University, and one of the forum’s longtime organisers, used the Iran-Israel conflict to illustrate the fragmentation and reshaping of the international order.

He argued that the US lacked real control over the crisis, as its position shifted dramatically within just 11 days, undermining any sense of strategic certainty. As for China’s global leadership, Yan candidly stated that China must carefully assess its capacity and resources before taking on broader leadership roles. Ultimately, he noted, China’s ability to lead will depend on how many countries can tangibly benefit from its rise.

The question is not whether China could have acted more forcefully, but whether doing so would have made the world more stable — or just more of the same.

In this sense, the Iran-Israel crisis has become an unlikely stage for a broader geopolitical contrast between two major powers. The question is not whether China could have acted more forcefully, but whether doing so would have made the world more stable — or just more of the same.

The world may not need more power brokers. It may need more principles. And China, for all its limitations, has made it clear that it seeks a future shaped not by force, but by norms, dialogue and global consensus. And it is betting that the world, in time, will come to value that ambition.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)