Xi’s long game: Trump’s tariffs threaten US influence in East Asia

Much as US President Donald Trump wants to protect US interests with his latest tariff announcement, the US might be getting the short end of the stick as other countries band together in response. Academic Hao Nan looks at the possible net result.

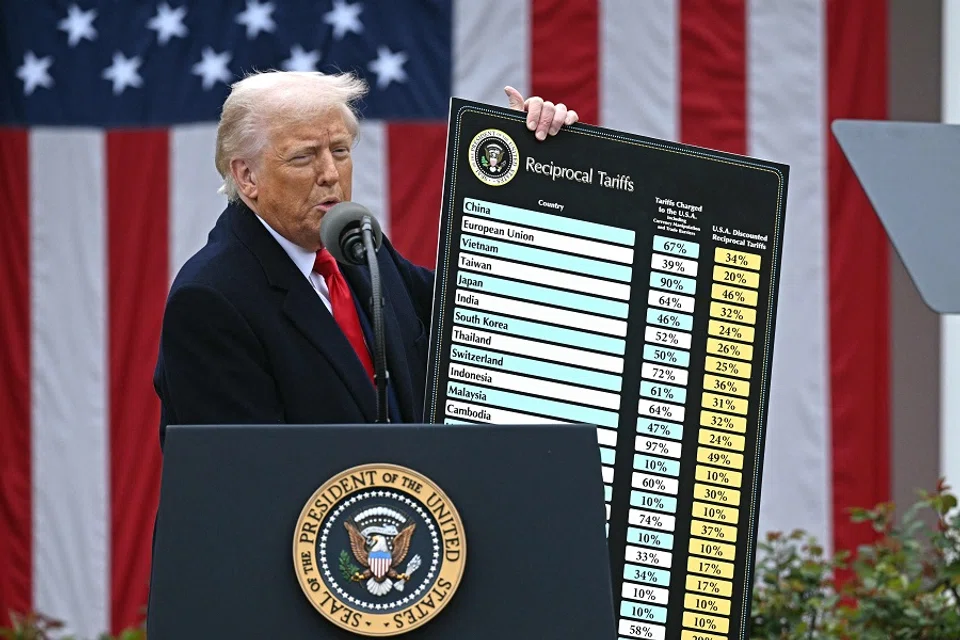

On 2 April 2025, US President Donald Trump declared a national economic emergency and imposed a sweeping set of reciprocal tariffs on US trading partners under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act. Effective 5 April, a baseline 10% tariff will apply to all countries, with individualised higher tariffs on nations with which the US runs the largest trade deficits. The East Asian region will suffer even more levies, with rates for mainland China at 34%, Japan at 24%, South Korea at 25% and Taiwan at 32%.

Pushing Asia away?

It is a bold, if controversial, resurrection of Trump’s economic nationalism, now formalised in his second term. While billed as a push to rebalance unfair trade practices, this policy may do more harm than good — particularly in East Asia, where US allies are already looking to one another, and to China, for economic stability and leadership.

The core risk is geopolitical: by enforcing an aggressive, unilateral trade agenda, the Trump administration could isolate the US from East Asia’s evolving economic architecture. Countries such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan — traditionally close American allies and partners — are responding not by bending, but by binding more tightly with regional economies, including China.

This could accelerate the momentum of multilateral agreements such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the long-stalled China-Japan-Korea Free Trade Agreement (CJK FTA). Instead of making America stronger, Trump’s tariffs may leave the US increasingly on the outside looking in.

China — though likely to retaliate soon — seems more inclined to take advantage of the strategic chance and play a longer game...

China playing the long game

China, for its part, has so far responded with relative restraint. While the Ministry of Commerce condemned Trump’s new tariffs and vowed countermeasures to safeguard its interests, no immediate retaliatory steps were announced. The new tariff adds 34% on top of two prior 10% rounds, totaling a 54% increase. This also adds to average 19% in tariffs from Trump’s first term, and fulfils Trump’s initial campaign vows of 60% tariffs on China.

The over 60% cumulative tariff burden on Chinese exports could cut China’s GDP growth by two percentage points — an unwelcome blow amid its efforts to maintain 5% growth. While Trump appears willing to impose self-damaging tariffs to dictate negotiations with China in the lead-up to the expected June summit with Xi, China — though likely to retaliate soon — seems more inclined to take advantage of the strategic chance and play a longer game: by forging deeper trade links with East Asian nations and positioning itself as a pillar of regional economic order, China could capitalise on American overreach. Active diplomacy around the CJK FTA and CPTPP could bolster China’s influence while softening the blow of US tariffs.

A shifting East Asia: rapprochement among China, Japan and South Korea

Japan’s response has been marked by frustration and recalibration. The Japanese government urged the US to exempt it from the tariffs, with Trade Minister Yoji Muto indicating the possibility of retaliation. Despite pledging to cumulate its total US investment to US$1 trillion, boosting LNG imports from the US, expanding defence cooperation, and compromising on the Nippon Steel’s purchase of US Steel, Japan was still hit with a 24% reciprocal tariff, apart from previously announced separate 25% duties on steel, aluminum and cars made outside the US. Tokyo’s diplomatic overtures, including a February summit between Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba and Trump, failed to secure exemptions.

While Japan is unlikely to retaliate directly, it will likely accelerate trade coordination with China and South Korea — reviving trilateral FTA talks and possibly to lift the barrier for China and South Korea’s accession to the CPTPP tacitly under its leadership, since the US’s withdrawal under Trump’s first term America’s long-standing advantage as Japan’s preferred economic partner is slipping.

South Korea’s situation is complicated by its domestic political instability left by President Yoon Suk-yeol’s controversial declaration of emergency martial law last December. While President Yoon’s impeachment is still in process, the opposition camp has been pushing for further impeachment of acting presidents — first Prime Minister Han Duck-soo, and later Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Finance and Economy Choi Sang-mok. The caretaker government struggled to mount an effective diplomatic defense, but only managed to send relatively lower-ranked Trade and Industry Minister Ahn Duk-geun to lobby the US stakeholders in January, February and March ahead of the tariffs.

Major South Korean chaebols like Hyundai, Samsung, and SK have also joined the government’s efforts to ramp up US investment in hopes of avoiding tariffs. Nevertheless, Korean exports to the US now face a 25% tariff, and Trump’s announcement of a 46% duty on imports from Vietnam — where Samsung and LG manufacture extensively — further strikes at Seoul’s regional and global supply chain.

... the recent rapprochement among China, Japan and South Korea...has already demonstrated the three countries’ intentions to work together to mitigate Trump’s tariff shocks, pointing to the CJK FTA and CPTPP.

With the country likely remaining in such a leaderless situation until mid-2025, the caretaker government is unlikely to risk direct confrontation with the US to retaliate. In this vein, it too is likely to seek relief through regional economic integration. With leadership weak at home and diplomacy faltering abroad, Seoul sees the CJK FTA and CPTPP as vital buffers against US protectionism.

In fact, the recent rapprochement among China, Japan and South Korea, evidenced by the recently concluded Trilateral Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Tokyo on 22 March, and the Trilateral Economic and Trade Ministers’ Meeting in Seoul on 30 March, has already demonstrated the three countries’ intentions to work together to mitigate Trump’s tariff shocks, pointing to the CJK FTA and CPTPP. The CJK Trilateral Cooperation, launched in 1999 in response to the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, is particularly known for its economic crisis-driven nature.

At the 1999 ASEAN+3 Summit in Manila, leaders from the three countries held their first informal breakfast meeting, agreeing to sponsor joint research on economic cooperation. This marked the beginning of formal trilateral engagement. In 2000, the three nations backed the Chiang Mai Initiative, creating East Asia’s first regional currency swap mechanism. The 2008 global financial crisis further deepened their cooperation. In December 2008, the first standalone China-Japan-Korea summit was held in Fukuoka, Japan, outside of the ASEAN+3 framework. Leaders emphasised regional collaboration to mitigate the crisis’s economic fallout and issued a joint statement promoting financial stability and trade facilitation.

Taiwan in a most precarious position

Beside the three major economic powerhouses in East Asia, Taiwan perhaps finds itself in the most precarious position of all. Facing a 32% tariff, Taiwan’s cabinet only called the tariffs “deeply unreasonable” and said it would raise the issue with the US government, demonstrating its limited leverage in negotiations with the US. In fact, the Lai administration, since its inauguration, has been continuously escalating tensions both domestically and in cross-strait relations, betting only on US support in its independence-seeking efforts.

While the Lai administration is busy with a major recall campaign targeting opposition lawmakers, in order to seize the legislative control, its most recent designation of mainland China as a “foreign hostile force” along with 17 countermeasures in restricting cross-strait exchanges have invoked the first large-scale island enriching drill this year, with mainland Chinese forces pushing further to Taiwan’s territorial seas and simulating strikes on key targets such as ports and energy facilities.

Excluded from regional FTAs and increasingly vulnerable to pressures from both the US and mainland China, Taiwan’s economic outlook is dimming.

Furthermore, the tariffs come not long after TSMC’s pledge of an additional US$100 billion in US investments and relocation of advanced production capacity to the US. This move, aimed at avoiding tariff penalties, illustrates that the insurance strategy comes at the expense of weakening Taiwan’s crucial strategic asset, the renowned “silicon shield”.

Excluded from regional FTAs and increasingly vulnerable to pressures from both the US and mainland China, Taiwan’s economic outlook is dimming. As a result, Taiwan may find itself with little choice but to further compromise on Trump’s terms. These developments could undercut Lai’s political standing ahead of the 2026 local elections and the 2028 presidential election.

Protecting US interests, or doing damage?

Trump justifies his sweeping tariff campaign as a moral and economic imperative. The White House argues that persistent trade deficits, non-reciprocal tariffs, and unfair practices such as currency manipulation and VAT disadvantages have gutted US manufacturing and endangered national security. But unilateral tariffs are a blunt tool. They risk alienating allies, encouraging global retaliation, and prompting the very economic realignment the US seeks to prevent. Instead of correcting imbalances, Trump’s approach may cement a new trade order in which the US plays a diminished role.

... Trump’s tariff policy, intended to secure American dominance, may instead accelerate its decline in the very region where it once held the most sway.

Already, there are signs this is happening. The RCEP, which includes China, Japan, and South Korea, now covers over 30% of global GDP. The CPTPP — initially envisioned as a US-led bulwark against Chinese trade dominance — has moved forward without American participation, with Japan and others even floating the idea of Chinese membership. Meanwhile, the China-Japan-Korea FTA, once bogged down by diplomatic tensions, is enjoying renewed momentum.

Furthermore, with South Korea hosting the APEC in 2025, China in 2026, Vietnam in 2027, East Asian countries in favour of free trade and multilateralism are holding the leverages in counteracting Trump’s approaches. Against this backdrop, Trump’s tariff policy, intended to secure American dominance, may instead accelerate its decline in the very region where it once held the most sway.

Trade is not just an economic tool — it is a pillar of foreign policy. The Trump administration’s reciprocal tariffs might be designed to rebuild American industry, but their broader effect could be to unravel decades of US leadership in East Asia. Economic engagement, not isolationism, has been the foundation of American power in the Pacific. By turning partners into adversaries and pushing them closer to Beijing, the US is jeopardising both its economic interests and its strategic position in the most vital region of the 21st century.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)