[Big read] Joe Wong: The Chinese stand-up comedian who performed at the White House

With a PhD in biochemistry and a bespectacled, unassuming appearance, Joe Wong does not fit the profile of a typical comedian. However, his perceptive, cross-cultural humour has endeared him to audiences in the US and China. The Chinese-American comedian tells Lianhe Zaobao journalist Zhang Heyang about his passion for stand-up comedy, performing in Chinese and English, and the challenges of bringing stand-up to China.

In the era of an “online traffic economy”, a hit online variety show can spark real-world trends. Since the breakout success of Rock & Roast Season 3 in 2020, watching and learning stand-up comedy has become a fashionable lifestyle among Chinese youths, using humour and satire to view everyday life from a fresh perspective. This wave of the “laughter economy” has also swiftly taken the Chinese-speaking world by storm, as evidenced by Singapore’s Can Can Comedy and Durian Comedy, and Malaysia’s BBK Network.

From sketch comedy (小品) to crosstalk (相声), China has long had its own comedic traditions. To understand how stand-up comedy (脱口秀) — or “American-style solo crosstalk” — entered the Chinese-speaking world, you have to talk about Chinese-American comedian Joe Wong (黄西).

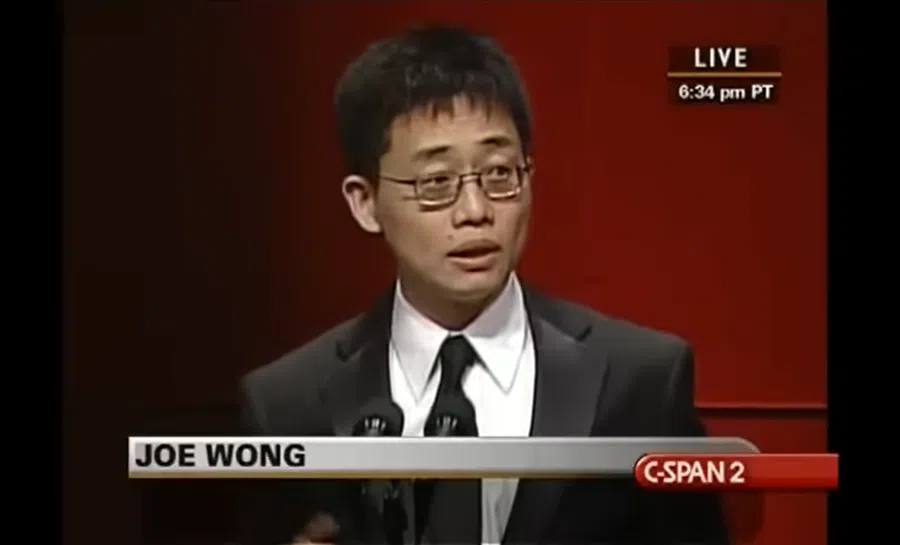

Around 2011, a video went viral online featuring a bespectacled middle-aged man with strong Chinese-accented English, delivering a comedic and somewhat offbeat “speech” at the White House Correspondents’ dinner. At that time, many Chinese people might not have been familiar with stand-up comedy. However, they were astonished that a Chinese person dared to roast Joe Biden, then the US vice-president, and make jokes about various American social issues, and be genuinely funny doing it.

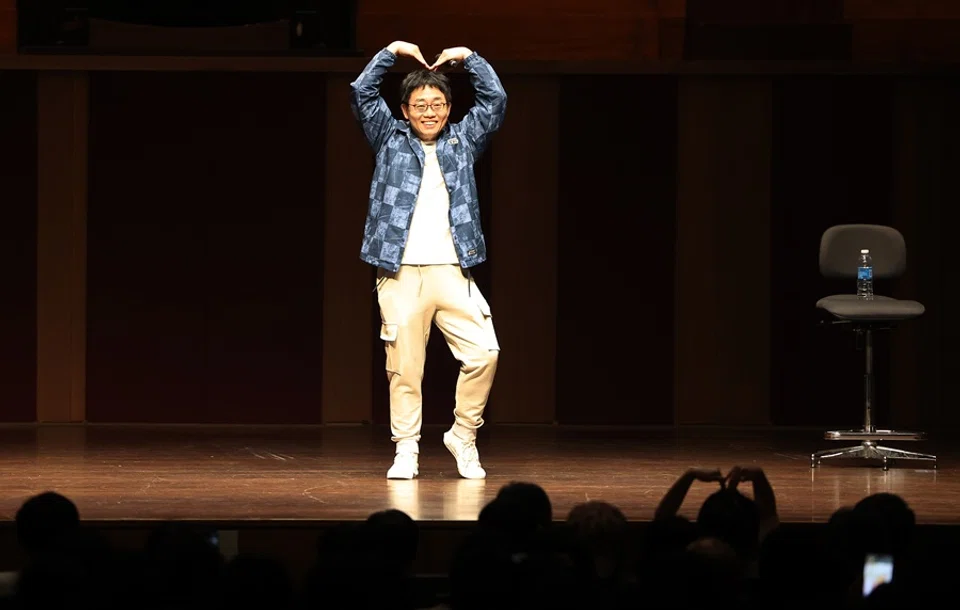

Ahead of his bilingual stand-up shows in Chinese and English on 22 July at Victoria Concert Hall, Lianhe Zaobao sat down with Wong to talk about the “sinicisation” of stand-up comedy.

From academic to comedian

Born in 1970, Wong’s early life exemplifies the “American dream”. Raised in a small city in Jilin province, northeast China, he gained admission to the Chinese Academy of Sciences based on his excellent academic performance and later went to Rice University in the US, where he earned a PhD in biochemistry. Although poised for a promising research career, workplace setbacks and the sense of alienation brought by his immigrant identity left him feeling weary and lost.

He first encountered stand-up comedy in Houston in 2002 and found that after a good laugh, his entire week felt much better. The following year, Wong started a new job in Boston and saw an ad in the newspaper for a stand-up comedy class — six sessions for just US$100. “I learned some basic stage skills, like how to structure a joke, how to hold the mic, how to move on stage — and started performing,” he recalled.

“... after getting into stand-up comedy, even when I did a terrible job, I still wanted to keep doing it. That’s when I realised — if you fail at something and still want to keep trying, maybe that’s what you’re meant to do.” — Joe Wong, Comedian

“I still vividly remember that someone came up to me after a show and said, ‘What you said might have been interesting, but I couldn’t quite understand,’” said Wong. “I wasn’t very good at first, but after watching some classmates perform, I realised American performers were doing pretty much the same thing. That gave me confidence — we were starting from the same place.”

“I felt like I didn’t know who I was in the past. But after getting into stand-up comedy, even when I did a terrible job, I still wanted to keep doing it. That’s when I realised — if you fail at something and still want to keep trying, maybe that’s what you’re meant to do.”

Bringing stand-up comedy to China

After the video of his performance at the 2010 White House Correspondents’ dinner went viral, Wong decided to become a full-time stand-up comedian. In 2013, he was invited to host CCTV’s interactive fact-checking show Is It True?, where he infused elements of stand-up comedy in his role as a host. He also founded his own comedy club (笑坊Joe’s Club) in Beijing, offering live shows and training for enthusiasts.

Back then, stand-up comedy was still a novelty in China. During live shows, the audience asked questions like: “Do you think my grandson should study abroad?” After the CCTV programme aired, some viewers even complained that Wong “did not take their questions seriously”. He recalled that those early years were not so much about performing stand-up as they were about educating people on what stand-up comedy actually was.

Meanwhile, at 笑坊Joe’s Club, audiences were sparse; not earning money from the performances was the norm. Still, Wong kept organising performances and offering training, and some audience members even wrote in or submitted scripts on their own. “We didn’t really plan to use others’ material, but one of our staff casually encouraged someone, and they actually got on stage — and now they’re a pretty decent stand-up comedian,” said Wong. “Many of today’s club owners across the country once stood on, or watched from, the stage of my club.”

“Oftentimes, it’s not that audiences don’t like it; they just haven’t had the chance to understand it yet.” — Wong

The challenges of doing stand-up in China

In 2017, iQIYI invited Wong to produce the online variety show CSM: China Stand-Up Comedy Megagame, inviting actors from across the country to compete. The eventual winner was Zhou Qimo, who would later become insanely popular. Although the show garnered over 100 million views, iQIYI cancelled it after just one season due to poor sponsorship.

Around the same time, Tencent’s Rock & Roast also failed to turn a profit in its first two seasons, but they persevered, and it was not until the third season that the show truly gained traction. On the fourth season of Rock & Roast, Wong teased Zhou — often called the “veteran of Chinese stand-up comedy” — saying, “If he’s the veteran, then I must be the ‘ghost’ of stand-up.”

“Nothing was wrong with the show. The biggest problem was giving up too early,” Wong said. In China, stand-up comedy is often seen as “out of place”, but in reality, the bigger challenge is the lack of patience and sustained investment. “This is the same as many foreign series — often they don’t catch on until the third or fourth season. Oftentimes, it’s not that audiences don’t like it; they just haven’t had the chance to understand it yet.”

The performance of Out of Place in Singapore is a new piece that Wong has been refining over the past year, with the main theme being cultural clashes. Wong cut his stand-up comedy teeth in the US, making a name for himself there performing in English. Some have suggested he might struggle to adapt if he returns to China. “Perhaps that could be the case, but for us comedians, a struggle to adapt is a valuable source of material.”

He recalled when he first returned to China, a producer asked him to translate a stand-up routine from English to Chinese in real time, which rendered him perplexed. “Translating directly from English to Chinese will not work; the humour is reliant on a cultural consensus unique to each language, and creating material in English and Chinese requires different modes of thinking.”

He discovered that English performances had a broader cultural consensus, with the tempo of audience responses more uniform, whereas Chinese performances were more complex and diverse.

Performing in both English and Chinese on the same night

A highlight of Wong’s Singapore performance is that he will deliver two special shows on the same night: the Chinese show Out of Place and the English show Twin Tariff. “I remember last year (2024) when I performed in Atlanta, someone attended both shows and remarked afterwards: you repeated one of your punchlines!”

As one of the rare few performers capable of creating and delivering stand-up comedy in both English and Chinese, Wong possesses a unique cultural perspective. He discovered that English performances had a broader cultural consensus, with the tempo of audience responses more uniform, whereas Chinese performances were more complex and diverse. He noted, “there’s a saying: people are fish, and culture is water. Often, you’re so much a part of it that you do not feel it.”

He touched on the generational differences among North American Chinese audiences; even among Chinese viewers, the reactions of “old overseas Chinese” and “new overseas Chinese” could be quite different. “The older group are those who immigrated in the 80s and 90s, and they often have a sense of admiration for the US. At that time, China was still developing, so they resonated more with the ‘American Ddeam’ and are more accepting of American humour. In contrast, many new overseas Chinese who arrived after 2010 are more critical of US society.”

This had a direct effect on the impact of his stand-up routines, especially for larger shows where he would tend to stick to “common tropes” revolving the initial phase of cultural adaptation for immigrants, and avoid topics that could polarise the audience. “If you go too deep, some people might laugh heartily, but others might not react at all.”

“They scroll through TikTok, RedNote and Instagram, watching stories by others about China, what Chinese cities look like, what new energy vehicles are like and they develop an interest in China, in turn leading to more attention being paid to language and cultural roots.” — Wong

Shift in attitude towards learning Mandarin in North America

At the same time, Wong noticed a subtle shift in North American attitudes towards learning Mandarin. In the past, the common perception was that second-and-third generation Chinese had poor Mandarin proficiency and were culturally distant; the story of how author Liu Yong took painstaking efforts to guide his son to learn Mandarin was widely known. Now, however, youths have turned the tables, berating their parents: “Why did you not let me learn Mandarin when I was young?”

Wong feels that this change is largely due to the internet. “They scroll through TikTok, RedNote and Instagram, watching stories by others about China, what Chinese cities look like, what new energy vehicles are like and they develop an interest in China, in turn leading to more attention being paid to language and cultural roots.”

He recalled several encounters with audience members at his Chinese-language shows in the US which surprised him. “Once when I performed at The Comedy Store on the West Coast, a white man approached me and greeted me in Chinese. He said he studied Mandarin for seven years, and was determined to have a chat with me.”

Some other audience members were young Americans learning Mandarin who became regulars at his Chinese performances — even if they could only understand very little, they wanted to develop a sense for the language. “These American students learning Chinese often come from very affluent families. For example, Donald Trump’s granddaughter and Joe Biden’s grandson are learning Chinese.”

Wong sees these as cultural phenomena born out of the rapid development of Chinese society. “The world changes so fast; it’s an entirely different landscape almost every few years. But no matter how times change, humanity’s need for laughter and joy will never go away.”

“Unlike skits or crosstalk, where two people play different roles to create a comedic effect by clashing with each other, stand-up is about telling your own story and talking about things happening around the audience in their everyday lives.” — Wong

Tracing the history of stand-up comedy in the US

Wong noted that some traced the history of American stand-up comedy back to the satirical author Mark Twain. “Back then, Twain invested in high-tech ventures such as the telephone and the light bulb, but he ended up in debt because of his investments. So, he toured the country giving lectures. He was humorous, and people loved listening to him.”

“The modern form of stand-up comedy we are familiar with was pioneered by Lenny Bruce in the 1950s and 60s. The US was not as open as it is now, and Bruce was jailed for touching on sensitive topics. He led a tough life. But he truly broke new ground with this form of comedy. Unlike skits or crosstalk, where two people play different roles to create a comedic effect by clashing with each other, stand-up is about telling your own story and talking about things happening around the audience in their everyday lives.” Wong also expressed interest in expanding novel forms of stand-up comedy in the future, such as incorporating it into a series or with more structured narratives.

In 2019 Wong performed an English show in Singapore, and the quick reactions of the Singaporean audience who could easily “catch the punchline” most impressed him. The Singaporean audience was also familiar with American societal themes. This time around, what Wong most looks forward to is the feedback from his Chinese show, as he had never performed it before and is curious to see if it will be “out of place”.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “双语脱口秀演员黄西 调侃时局解读众生”.