A spice of laughter: Inside the world of English stand-up comedy in Shanghai

English stand-up comedy in China is finding fans among a growing number of young Chinese, observes Shanghai-based writer Kyle Muntz. He speaks with Spicy Comedy’s Norah Yang and other comedians lighting up the Shanghai stand-up comedy scene.

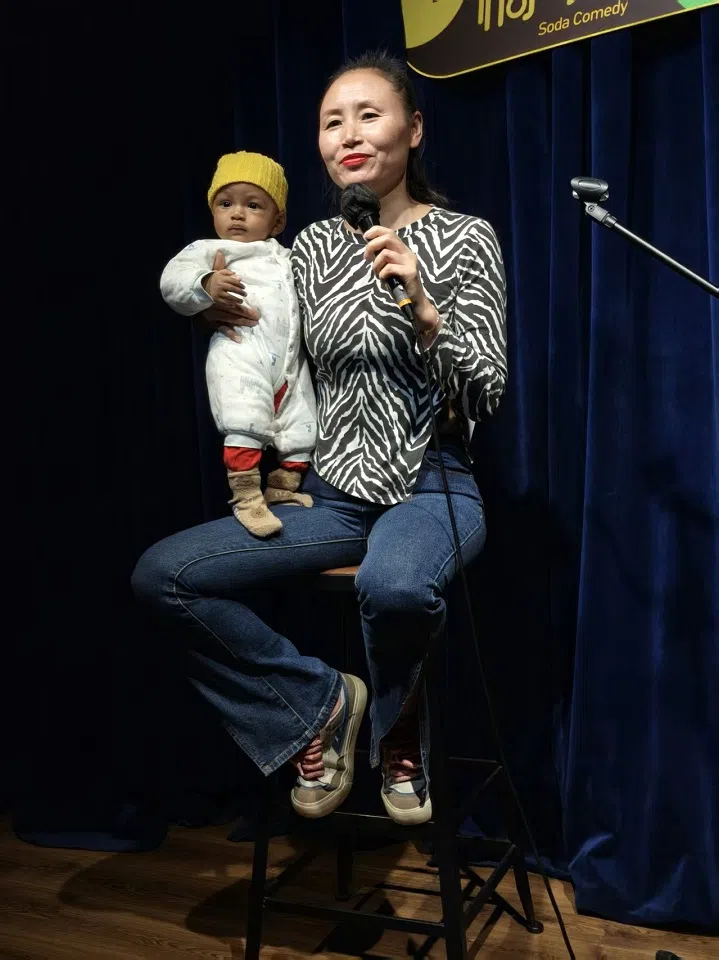

(All photos provided by Spicy Comedy unless otherwise stated.)

A few years ago, English stand-up comedy was a rare occurrence in Shanghai — but today, there are sold-out shows nearly every day of the week. Much of this is the work of Norah Yang, who founded Spicy Comedy, China’s first full-time multilingual comedy club in 2021, offering shows in English, Mandarin and even Shanghainese. With over a million followers on Rednote and a dozen comedians in her employ, her success seems only to be growing.

“She’s the Joe Rogan of English comedy in China,” says Ian B (Ian Badenhorst), a longtime Shanghai stand-up veteran who currently hosts his own sold-out shows at Spicy. “There’s nobody like her.”

But things haven’t always gone so well. Half a decade ago, when Norah was still an office worker, she brought her parents to a show during their family reunion.That night, Norah performed with three other comedians, but there were only four people in the audience, and it was a disaster. “They thought it was not funny and that it was offensive, especially when one lady was looking at my mom and dad in a suggestive way. The first thing they said was, don’t quit your job for this. There’s no future in it.”

... Chinese audiences are just interested in different things. And a new, local industry, led by comedians like Norah, has emerged to fill the gap.

At that point, despite her early success on social media, much of Norah’s burgeoning career was kept secret from her parents. For a while, the situation seemed hopeless. “But it changed when they started to hear from their friends about me. They would say, ‘Your daughter is doing really good, she should keep at it.’ So it got social validation, and then they started to think, okay, comedy seems legit, it’s an important thing in China now. And when I finally quit my job to run the Spicy Comedy club full-time, they supported me.”

Norah’s career has grown alongside Chinese stand-up comedy as a whole, but to understand her success, it’s necessary to understand her audience.

In China, who is interested in English comedy?

According to Ian B, “There’s been English comedy in China as long as there’s been foreigners, but things are different now than they used to be.” Much of this began with a club named Kung Fu Komedy, who frequently hosted local expat comedians or invited comedians from overseas. In the beginning, these shows aimed primarily at expats, with more and more Chinese audience members attending gradually over time. However, Ian recalls, even shows by prestigious overseas comedians often flopped horribly. “It wasn’t a language problem. People understood, but they just didn’t like the jokes — a lot of times it was only the expats who laughed.”

“English comedy is almost all girls, and most of them are young. They’re curious about the world, and I think girls are especially interested in language.” — Li Ying, Comedian

Clearly, Ian discovered, Chinese audiences are just interested in different things. And a new, local industry, led by comedians like Norah, has emerged to fill the gap.

Li Ying, owner and operator of Herlarious comedy club, which offers shows entirely in English with a rotating list of comedians, was there when it was happening. “At first, when I started, the scene was like a white boy’s club. I saw a couple Chinese girls, and they looked pretty timid. Today, however, the comedians onstage are mostly Chinese, and the gender balance has undergone a seismic shift. “English comedy is almost all girls, and most of them are young. They’re curious about the world, and I think girls are especially interested in language.”

Originally from northeast China, Li Ying’s show revolves around stories of her early childhood and living abroad in Malaysia. As one of Norah’s few competitors in Shanghai’s English stand-up scene, Li Ying has toured much of China — though unlike Norah, Li Ying’s show is exclusively in English. While China’s full-time English standup scene is primarily based in the country’s largest cities and online, Li Ying has done shows all around the country as a special guest in Mandarin-speaking comedy clubs. She’s also observed that no matter where she goes in China, there is an always an audience looking for something new and exciting from English comedy.

In Shanghai, however, Li Ying’s audience is primarily made up of expats, with little presence on Chinese social media, and advertising offered primarily in English-language venues. “It’s not easy,” she says, particularly in recent years as Shanghai’s expat community has continued to shrink. “We’re not doing enough on Chinese social media. But I don’t want to sit there and edit a video for an hour. I’d rather write jokes or perform. I just love doing this, you know?”

This puts Li Ying in stark contrast with Spicy, whose strategy focuses on reaching Chinese young people through platforms like Rednote.

“They’re the online generation... the first batch to understand what comedy is about, and sometimes they bring their family and friends. The older generation, like my mom — they don’t even want to be in the audience, so how would they be able to want to become a comedian?” — Norah Yang, Comedian

“They’re the online generation,” Norah explains of both the comedians and the audience, “the first batch to understand what comedy is about, and sometimes they bring their family and friends. The older generation, like my mom — they don’t even want to be in the audience, so how would they be able to want to become a comedian? This is changing, but a lot of them still think it’s a waste of time or just young people talking shit.”

Overall, the average age of comedians in China is as low as 20 or 25, whereas abroad it’s closer to 45, and Norah has “even seen grandpa comedians”. This, she believes, is essential for understanding the importance of comedy in a rapidly changing country.

So, what are Chinese audiences interested in?

As one of the fastest growing economies on the planet, China’s rapid modernisation has created an immense hunger for new things. “People are looking for more ways to have fun,” Norah explains. “We have karaoke, restaurants, escape rooms and board games, but we don’t have a lot of new forms of performances like theatre or musicals. Now it’s popular enough that people will even package traditional Chinese comedy as stand-up.”

The topics are super local, like education pressure, mortgages pressure or what it’s like to be in the workforce. — Yang

These days, some companies even hire a comedian to perform for their employees — but Norah attributes her success to timing. “I think I was lucky, because I was the first one to put clips from English shows online. Today, comedy is becoming nationalised on big platforms like Tencent, and there are big shows that a lot of people watch. But those shows are mostly competitions or dramas, rather than pure stand-up.”

According to Ian B, much of Norah’s success can be attributed to her presence on social media, which is largely managed by her partner, who co-runs Spicy. Ian suspects a large percentage of Spicy’s audience began as Norah’s fans before becoming devotees of the other comedians.

Why English? Norah explains that, in the beginning, it wasn’t intentional — after a show by an American comedian, she was invited onstage to perform in English, and that became her act. “I started out my career going viral by putting out English content on the internet, probably because I was the first one to do it. But the English market is concentrated, with a smaller audience and fewer performers. The mass audience is Chinese, and language-wise there will be a lot more people who understand Mandarin.”

With that in mind, Norah does her best to give the audience what they’re interested in. “Chinese culture is really important to the comedy that gets popular here,” Norah explains. “The topics are super local, like education pressure, mortgages pressure or what it’s like to be in the workforce.”

Whether you’re in New York or Shanghai, it doesn’t matter — life’s tough. There’s so many things to talk about and people need to forget about their job. — Li

Frankie A, a Hong Kong/Lebanese comedian who hosts many of the shows at Spicy, agrees. “Local stuff works better. Talk about how buying a house in Pudong sucks, and that gets people excited and laughing. The problems people face can be funny, because people are finding it hard to date. Plus, punching up is funny, like helping people complain about their bosses or celebrities or whatever. But say something about racism and you might not get a big reaction, like in America.”

For Li Ying, comedy is also a unique means of coping with the stress of modern life. Many audience members might attend smaller, less formal shows as social events, looking to make friends or practice English, but most of these people have something in common. “Whether you’re in New York or Shanghai, it doesn’t matter — life’s tough. There’s so many things to talk about and people need to forget about their job. For a lot of people, it’s escapism. There’s booze, jokes. That’s comedy!”

... I think comedy should be all about having fun. But when it’s culture related, I think learning is always in the Chinese genes, so audiences want to be enlightened rather than just entertained.

In other cases, comedy can be a useful way of learning about the world outside the country. For example, when You Baiwan — a viral English teacher turned comedian who now headlines shows at Spicy — was in England as a student, she ran into constant small difficulties that have become material for her comedy. “That stuff really stressed me out, like little things I couldn’t do or understand. But I told it to other people and they thought it was funny.

Despite all this growth, there’s another trend with deeper roots in Chinese culture that Norah doesn’t approve of. “I think more and more people are looking for comedy with messages, which is different from Western comedy. We like learning from everything, so I’ll read on the internet about how one person’s comedy is ‘higher’ just because they’ve got a message — even if they’re not funny! I don’t agree with this, because I think comedy should be all about having fun. But when it’s culture related, I think learning is always in the Chinese genes, so audiences want to be enlightened rather than just entertained.”

Li Ying believes you also need to think about what the audience wants. “If you talk about sad stuff, they don’t laugh. They’ll just feel sorry for you if you make a self-deprecating joke. It has a lot of things to do with the culture, cause like, you know, the way we grew up. The way I see it, we get a lot of criticism in life, and that’s enough. No need to also criticise yourself on stage.”

Owning a business

Increasingly, Norah admits, the stress of running a business is cutting into her time as a creator. When she was still an employee working in an office, her biggest team had been six; at Spicy, they have over a dozen comedians and far more interns, and scaling up is a constant logistical challenge. “At first, I’d hoped my partner could run the company for me, while I could focus on comedy. But of course, that isn’t how it goes. It’s important to work with the comedians, help them grow, and there are a lot of things I need to do myself.”

It’s very mild but you can feel sexual harassment when you’re the only lady in the whole room. Luckily, when you are in power, when you have your own comedy club, nobody will give that to you anymore. Power comes with respect. That’s just how it is. — Yang

But even Spicy Comedy itself, as a permanent venue with an established roster of comedians doing regular shows under contract, is unlike anything you’d find in America. “In the West, comics have an agent and a manager. Comedy is very individualistic,” says Ian B. “But Spicy Comedy has like 15 people, and here we’re all part of a close-knit group. We’re in it together.”

From Norah’s perspective, running the company has also led to a different kind of personal success. “When you’re a woman, people sometimes say you aren’t funny enough, or it will be very hard for you to find a boyfriend or husband. It’s very mild but you can feel sexual harassment when you’re the only lady in the whole room. Luckily, when you are in power, when you have your own comedy club, nobody will give that to you anymore. Power comes with respect. That’s just how it is.”

The future of Norah and Spicy Comedy

Looking forward, Norah and Spicy aim to expand beyond Shanghai with shows in Beijing, Hangzhou, Xiamen, and even as far as Wuhan. No matter where they go in China, Norah has found, while the local comedy clubs specialise primarily in Mandarin, there’s always a big audience for comedy in English. But she’s also done shows abroad in America, Australia, and other countries, and in the process she was surprised to discover that, without ever intending to, she’s also become a cultural ambassador.

“Abroad,” says Norah, “people abroad envision China as this ancient place, like it’s mysterious or like oriental and this and that. They’ve never met a Chinese person, and they don’t know anything about the country. So when I travel, I think it’s important to bring real Chinese stories to other countries. It doesn’t matter that what happens in Shanghai is the same thing that happens in New York. Actually, I think that might be the point!”