Cai Guo-Qiang and the fireworks that disturbed China’s dragon vein

Celebrated Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang sought to ignite a “rising dragon” across Tibet’s sky. Instead, the flames exposed a clash between modern art and the ancient spirit of the land. Academic Zhang Tiankan looks at the relationship between art, nature and myths.

On 15 October, the municipal government of Shigatse in Tibet, China, released a report on the investigation and handling of Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s “rising dragon” pyrotechnics display.

According to the notice, the relevant administrative authorities have filed a case against Cai’s studio in Beijing for suspected violations of the law. The sponsor, Arc’teryx, will bear legal responsibility for ecological damage compensation and environmental restoration, and several officials from Gyantse County have also been held accountable.

In 2008, he [Cai] served as visual and special effects director for the Beijing Olympic Games opening and closing ceremonies, designing several firework displays, including the much-debated “Footprints of History” sequence.

The ‘rising dragon’

The “rising dragon” refers to a performance art piece jointly produced by Arc’teryx and Cai’s studio on the evening of 19 September.

At an altitude of about 5,500 metres in the Relong area of Gyantse, located in the Tibetan Himalayas, rows of colourful pyrotechnics were set off along a mountain ridge, creating a dynamic spectacle resembling a rising dragon.

The work revealed contradictions and stirred debate around whether it was art or destruction, and if it honoured or violated traditional culture.

Cai’s work has long been controversial, though it has also received critical acclaim and international awards. His signature style involves large-scale fireworks and gunpowder trajectories across landscapes or architectural surfaces, creating monumental burning images.

In 2008, he served as visual and special effects director for the Beijing Olympic Games opening and closing ceremonies, designing several firework displays, including the much-debated “Footprints of History” sequence.

Public discussion about Cai’s work often revolves around the question of artistic freedom and its boundaries.

Artistic freedom and its boundaries

Artistic freedom — or the freedom of artistic creation and expression — refers to an artist’s right to freely express, explore, and convey ideas, emotions, and creativity in the process of creation. It is a part of freedom of speech and cultural freedom, emphasising that creative and expressive liberty in the arts should not be subject to government censorship, political interference, religious pressure, or other external constraints. Artists have the right to use their works to reflect on social issues, express dissatisfaction with injustice and inequality, and criticise governments or other forms of authority.

However, as with everything, artistic freedom is not limitless, but has boundaries. The most fundamental boundary is that it must not violate a society’s laws and regulations: for example, it must not infringe intellectual property rights, nor cause damage to the ecological environment.

At the same time, artistic freedom should respect the moral and ethical norms recognised and accepted by society, avoiding the spread of hatred, discrimination, or actions that cause discomfort or harm to others.

Therefore, artistic freedom requires a proper balance between freedom and restraint. According to the investigation’s findings, the “rising dragon” show crossed the boundary of environmental protection, and was thus deemed inappropriate and even harmful.

Authoritative professional institutions and experts established 75 monitoring points for air, surface water, and soil conditions, as well as 90 biodiversity monitoring sites, and deployed 30 infrared cameras.

Investigation into environmental impact

The investigation found that the fireworks were set off on a mountain slope at an altitude of 4,670 to 5,020 metres, affecting 30.06 hectares of grassland. A total of 1,050 fireworks units were ignited, with a duration of approximately 52 seconds.

Authoritative professional institutions and experts established 75 monitoring points for air, surface water, and soil conditions, as well as 90 biodiversity monitoring sites, and deployed 30 infrared cameras. After on-site inspections, systematic sampling, data analysis, and expert evaluation, they produced a report on ecological disturbance in Gyantse, Shigatse city.

The report concluded that this incident constituted a human disturbance activity conducted in an ecologically sensitive highland area. Its impact on the environment was primarily localised, with limited short-term pollution and destruction, but potential ecological risks require continued monitoring and follow-up.

In addition, Cai’s art studio was found to have entered ecologically fragile grassland areas and carried out activities that damaged the grassland, and to have failed to fully clean up fireworks residues, such as powder and plastic debris. These actions are suspected of violating the Law on Ecological Protection of the Tibetan Plateau, and the Grassland Law.

Accordingly, the relevant administrative authorities in Shigatse city have filed a legal case to investigate and handle these violations.

Both Fuxi and Nüwa were described as having human heads and serpentine (or dragon-like) bodies, forming the mythological origin of the idea that the Chinese people are descendants of the dragon.

Dragons in Chinese culture

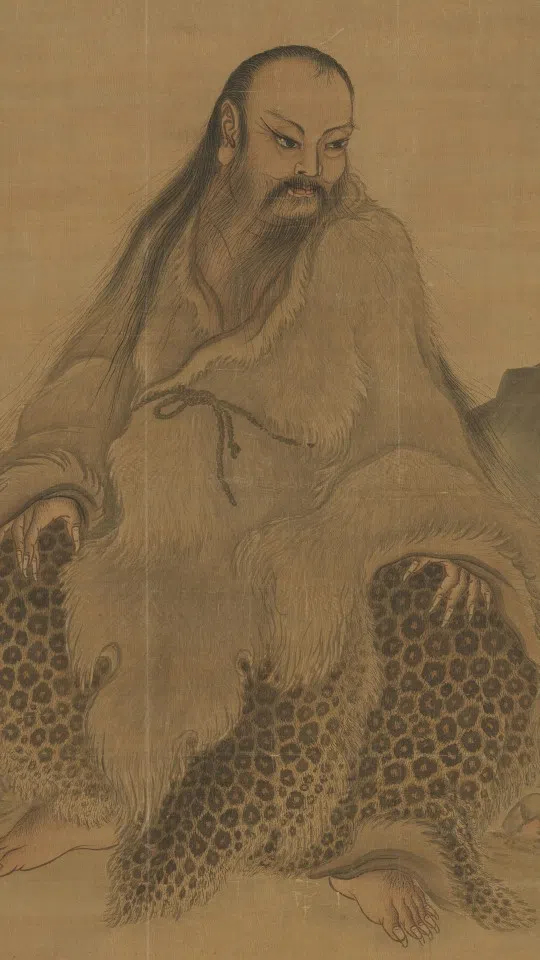

The “rising dragon” fireworks show also reveals a paradox in the interpretation and inheritance of traditional culture. The “rising dragon” symbolises the Chinese nation or Chinese civilisation rising like a dragon — an image rooted in the ancient dragon totem, which dates back about 8,000 years to the Neolithic era of Fuxi (伏羲).

According to classical texts such as The Book of Documents (《尚书》) and The Liezi (《列子》), Fuxi, regarded as the ancestral progenitor of humankind in Chinese mythology, was the forefather of the dragon. It is said that his mother, Huaxu, conceived him after stepping on a giant footprint in the Lei Marsh area (around present-day Juancheng in Heze, Shandong province). Nüwa, his sister, shared the same divine lineage. Both Fuxi and Nüwa were described as having human heads and serpentine (or dragon-like) bodies, forming the mythological origin of the idea that the Chinese people are descendants of the dragon.

From Fuxi onwards, the dragon lineage of China is said to be divided into one main branch and three sub-branches. The principal line was that of Fuxi himself — this was split into the Chennong 辰农 branch (represented by Shennong, the mythological Chinese ruler known as the first Flame Emperor Yandi 炎帝), the Longlong 竜隆 branch (represented by the Yellow Emperor Huangdi 黄帝 and his Gongsun and Xuanyuan clans), and the Xiuji 修己 branch (represented by the mythological being Chiyou 蚩尤).

Later, the Zhou kings became the first rulers to wear dragon robes, and over thousands of years, the Chinese people came to call themselves “descendants of the dragon”. This concept originates from ancient totems and mythological legends, not from historical fact. Nevertheless, as a cultural symbol, the dragon serves as a powerful metaphor for celebrating and expressing the vitality of Chinese life and identity.

Moreover, Cai’s representative work “Project to Extend the Great Wall of China by 10,000 Metres: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 10” (1993) also explores the theme of dragon culture. In that piece, Cai laid out nearly ten kilometres of gunpowder fuse along the western end of the Great Wall at the edge of the Gobi Desert. After about 15 minutes of ignition, the fuses created a fiery trail resembling a giant dragon winding through the dunes, symbolising the historical and mythological tradition of the Chinese empire.

However, in attempting to portray the “dragon vein” (龙脉, longmai), the work instead resulted in a profound contradiction — it damaged the very thing it sought to celebrate.

According to feng shui masters, the orientation, momentum, and shape of the dragon vein determine the auspiciousness of a location, influencing not only its geographical fortune but also the well-being and prosperity of future generations.

In traditional Chinese cosmology and feng shui, mountain ranges are likened to dragon veins, representing the flow of vital energy through the landscape. This has become a concept in feng shui, with the term referring specifically to the undulating contours and directions of mountain ranges, named so because their forms resemble dragons.

According to feng shui masters, the orientation, momentum, and shape of the dragon vein determine the auspiciousness of a location, influencing not only its geographical fortune but also the well-being and prosperity of future generations.

Dragon veins are further categorised into roots, trunks, branches, and leaves. Based on their direction and form, they can also be classified as coiling dragons, descending dragons, soaring dragons, or reposing dragons, and so on.

Dragon veins in China

The Kunlun Mountains are regarded as the “ancestor of all mountains” and the “source of all dragon veins” — the primordial or root dragon (祖龙, zulong). From Kunlun, dragon veins extend outward across the world. In feng shui, China’s dragon veins are typically divided into three main trunk veins.

The first is the Northern Dragon, which originates from the Kunlun Mountains, extending northeast along the Yellow River, passing through Qinghai, Gansu, Shanxi, and Hebei, and finally reaching Northeast China and the Korean Peninsula, with Beijing and Tianjin situated along this vein.

The second is the Central Dragon, lying between the Yangtze River and the Yellow River. It passes through Sichuan, Shaanxi, Hubei, Anhui, Shandong, and other provinces, and ends at the Bohai Sea. Major cities such as Xi’an, Luoyang, and Jinan belong to this lineage.

The third is the Southern Dragon, which follows the Yangtze River southward through Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi, Hunan, Jiangxi, Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu, finally reaching the sea. Cities such as Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Fuzhou are situated along this vein.

Areas where a dragon vein’s spiritual energy (qi) gathers and flourishes — metaphorically “blooms and bears fruit” — are considered land with excellent feng shui, or dragon lairs (龙穴).

Ruining the dragon vein?

A more vivid analogy would be: earth is the dragon’s flesh, stone its bones, and vegetation its hair, which reflects the Chinese people’s simple understanding of nature. And since earth is the dragon’s flesh, stone its bones, and vegetation its hair, then these elements should be protected, not destroyed.

So, setting off fireworks in the Himalayas to symbolise a “rising dragon” actually resulted in the destruction of the dragon vein itself.

Although the Himalayas lie along the southern edge of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and the Kunlun Mountains stand in western China, both are regarded as dragon veins of China and even the world, being regions of extreme ecological fragility, as proven in the latest investigation.

Therefore, the so-called “rising dragon” fireworks display was, in truth, an exercise in futility — a case of seeking fish by climbing a tree, completely at odds with its original intention.

![[Big read] Prayers and packed bags: How China’s youth are navigating a jobless future](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/16c6d4d5346edf02a0455054f2f7c9bf5e238af6a1cc83d5c052e875fe301fc7)