How award-winning athletes became ‘Taiwan’s Glory’

Sports and politics are intertwined, with the Olympic ideal often intensifying rivalry, says Taiwanese academic Ho Ming-sho. In Taiwan’s case, the contentious nature of its statehood has elevated its star athletes to symbols of “Taiwan’s Glory”, a phenomenon that carries significant and far-reaching implications.

In the late evening of 4 August, many Taiwanese eagerly watched the live broadcast of the men’s badminton doubles final at the Paris Olympics. When reigning champions Lee Yang and Wang Chi-Lin successfully defended their title against their Chinese rivals, the whole island erupted in celebration.

Likewise, on the early morning of 11 August, dedicated Taiwanese fans stayed awake to watch female featherweight boxer Lin Yu-ting compete in her championship challenge. To the delight of her supporters, Lin secured her first Olympic gold medal.

‘Taiwan’s Glory’ past and present

In their homeland, Lee, Wang, and Lin are not just celebrated athletes; they are widely revered as “Taiwan’s Glory” (Taiwan zhi guang). While it’s understandable that international competitions can spark national pride and strengthen solidarity, the eagerness of Taiwanese people to bestow such heroic titles on their sports figures calls for closer examination.

What’s more puzzling is that Taiwan doesn’t typically excel in physical sports. In the previous Tokyo Olympics, Taiwan achieved a record number of 12 medals, yet it ranked only 34th globally, far below what might be expected given its economic stature.

After each championship victory, President Chiang Ching-kuo would promptly issue congratulatory messages, always highlighting the resilient and strenuous efforts of the “Chinese youth” (zhonghua shaonian).

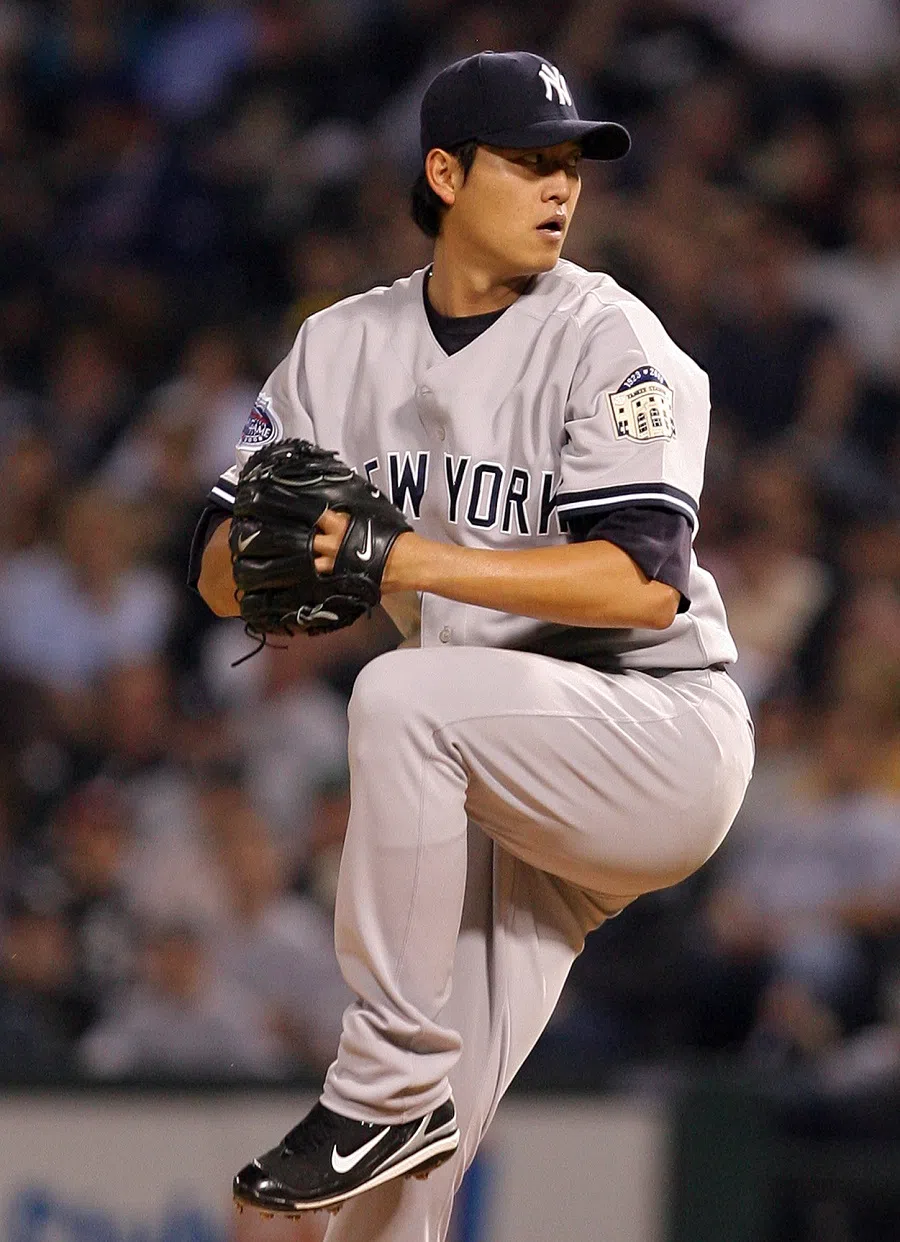

The term “Taiwan’s Glory” was first used to describe former Yankee pitcher Wang Chien-Ming, who made his debut in 2005. In 2006 and 2007, Wang achieved an impressive back-to-back 19 wins per season. His outstanding performance led to live broadcasts of Yankee games on Taiwan’s public television, introducing many Taiwanese to the culture of American Major League Baseball.

Athletic achievements linked to political identity

From a historical perspective, this is not the first time Taiwan’s political identity has been closely linked to athletic achievements. In 1969, Taiwan’s elementary school boys dominated the World Little League Baseball Series in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, winning 17 consecutive titles.

The unexpected success of these young baseball players greatly boosted Taiwan’s morale, with people eagerly staying up late to watch the satellite broadcasts. After each championship victory, President Chiang Ching-kuo would promptly issue congratulatory messages, always highlighting the resilient and strenuous efforts of the “Chinese youth” (zhonghua shaonian).

As historian Andrew D. Morris observed, baseball, initially introduced by the Japanese as a civilising and westernising project, later became a shared identity among native Taiwanese in the postwar era. Interestingly, many young players representing Taiwan on the international stage were Austronesian indigenous people. Thus, a colonial legacy unexpectedly became one of the few remaining pillars supporting the Nationalist government’s increasingly challenged claim to represent all of China.

For nearly half a century, Taiwan’s little league baseball players and the 2024 Olympic gold medalists captured the national spotlight and were widely seen as representing the entire nation. However, this sense of déjà vu was more than just a nostalgic echo of the Cold War era.

In the past, the authoritarian regime used the national pastime to compensate for its legitimacy deficit. Interestingly, while the mainland-dominated government promoted basketball, it discouraged baseball, which still retained many elements of Japanese culture. Professional baseball games were not permitted until martial law was lifted in 1987.

Through these international competitions, Taiwanese rallied around their athletes, finding in these events one of the few opportunities to assert their identity loudly and clearly.

Expressing shared aspirations

In contrast, democratisation allowed the Taiwanese to freely explore their own identity. A strong wave of indigenisation emerged, and people became increasingly unwilling to accept the idea that their athletes represented a fictitious “Chinese nationhood”.

Furthermore, as encounters with rivals from the People’s Republic of China became more frequent in international arenas, Taiwanese naturally supported their own team and grew increasingly resentful of the official name “Chinese Taipei”. Through these international competitions, Taiwanese rallied around their athletes, finding in these events one of the few opportunities to assert their identity loudly and clearly.

International sports have emerged as a powerful way for Taiwanese people to express their shared aspirations. This drive intensified when some supporters in Paris had their banners or posters removed for featuring the word “Taiwan” or the island’s shape. Even the flag of the Republic of China was not allowed. Undeterred, resourceful fans found alternatives, using symbols like Formosa black bears, bubble teas, or even Taiwan independence flags to convey their statement.

As a long-time supporter of the Tainan-based Uni-Lions Team, Lai selected baseball jackets as his official campaign uniforms, and his election slogan, “Team Taiwan”, closely echoed the phrase “supporting Taiwan” (ting taiwan).

Politicians associating with athletes

A 2013 survey study by the Institute of Sociology at Academia Sinica highlighted the political significance of sports. When asked what made them proud of Taiwan, 85.8% of respondents chose “sports achievement” as the top reason. Notably, other options like “treating everyone equally” (67.3%), democracy (44.1%), and “economic performance” (41.6%) ranked considerably lower.

With the widespread enthusiasm for “Taiwan’s glory”, it has become increasingly common for politicians from various parties to associate themselves with successful athletes. Legislators, city mayors, and municipal councillors often attend live broadcast rallies to cheer on their national heroes. After the games, their social media accounts — Facebook, Instagram and Threads — are promptly updated with congratulatory messages when the team wins, and words of encouragement when they lose.

Given the strong connection between athletic performance and collective identity, the ruling Democratic Progressive Party, which advocates for autonomy and self-determination, seemed particularly well-positioned to capitalise on this sentiment.

When President Lai Ching-te unveiled his campaign headquarters last October, the space featured numerous elements from baseball culture, including infield dirt, outfield grass, and a wall adorned with giant baseballs. Visitors were encouraged to use cheering bats to show their support. As a long-time supporter of the Tainan-based Uni-Lions Team, Lai selected baseball jackets as his official campaign uniforms, and his election slogan, “Team Taiwan”, closely echoed the phrase “supporting Taiwan” (ting taiwan).

Although Chinese Nationalist (Kuomintang) politicians were equally eager to show their support for “Taiwan’s Glory”, they were hesitant to make such an explicit connection to Taiwanese identity in their electoral campaigns.

In summary, sports and politics are inevitably intertwined, and the noble Olympic ideal of fostering international respect and friendship often ends up exacerbating rivalry and competition.

Like many other places, Taiwan is deeply entangled in this political game. However, its contested statehood and unfulfilled aspirations have led to the emergence of the “Taiwan’s Glory” phenomenon, which is likely to have significant repercussions both internationally and domestically in the years to come.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)