Lu Xun smoked — should his mural? China rethinks its icons

A complaint against a mural depicting Chinese literary giant Lu Xun smoking has sparked widespread debate on preserving the authenticity of historical fact, warts and all. Lianhe Zaobao China Desk takes a look at the uproar.

After the recent craze for the “Lu Xun sweater vest” — a popular fashion trend inspired by the style of the famous Chinese writer — a new mural showing Lu Xun smoking has become the latest topic everyone in China is talking about.

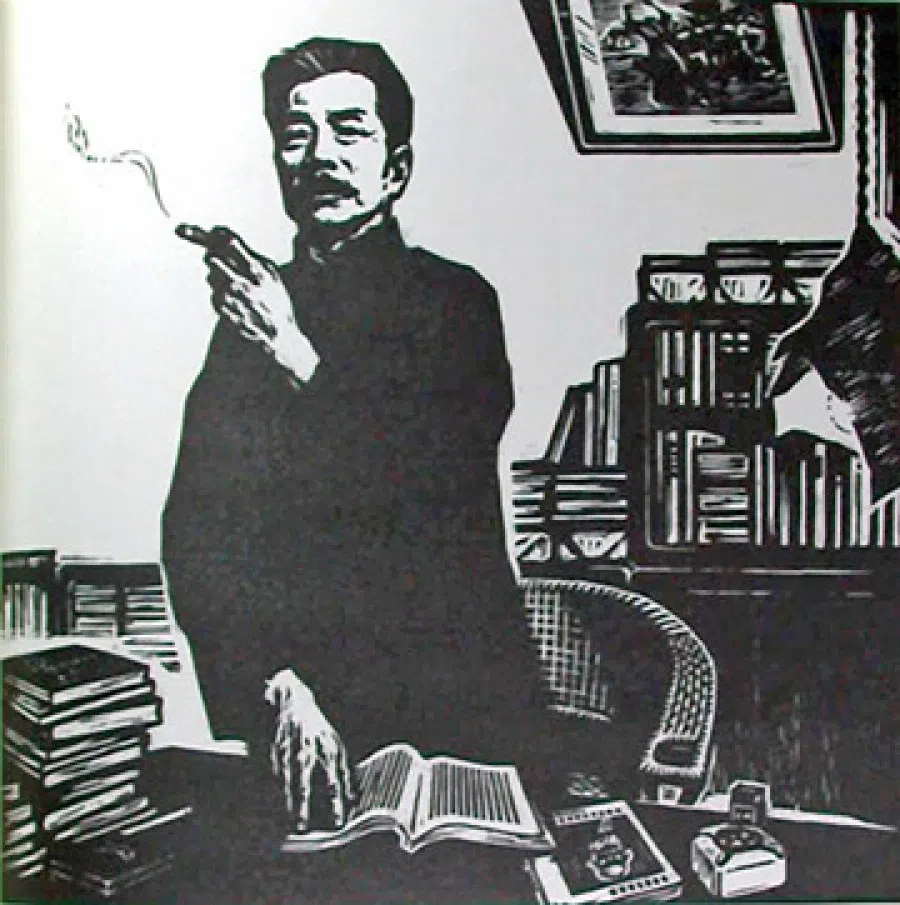

The mural at the Lu Xun Memorial Hall — in the writer’s hometown of Shaoxing, Zhejiang province — shows him in his signature long robe, sharp eyes gazing into the distance, with a lit cigarette between his fingers.

Many visitors have shared photos on social media of their trips there, just to flick a lighter in front of the mural and get a shot of themselves “lighting a cigarette for Mr Lu Xun”, making the mural a popular stop to “check-in”.

... she had examined many woodblock prints of Lu Xun and found that in the original image, the smoke trail was smaller, and the background clearly showed a study, prompting her to submit a second complaint.

However, a recent complaint from a tourist surnamed Sun has made this internet-famous wall even more popular.

Complaint against historical fact

Sun wrote online that the mural of Lu Xun holding a cigarette was inappropriate. On 22 August, she lodged an official complaint, suggesting that the image be changed so that Lu Xun’s right hand is clenched into a fist instead of holding a cigarette.

The original picture showed Lu Xun smoking at home, but the mural had removed the background. She argued that this could encourage people to gather outdoors to smoke, posing health risks to others, and might even be misleading.

In an interview with Shangyou News, Sun described herself as a tobacco-control volunteer who takes note of issues related to smoking bans in public spaces. She said that she had examined many woodblock prints of Lu Xun and found that in the original image, the smoke trail was smaller, and the background clearly showed a study, prompting her to submit a second complaint.

In response to her request to alter the mural, the Shaoxing Lu Xun Memorial Hall issued a statement on the evening of 25 August: they will maintain respect for Lu Xun, history and art, and will not easily change the established image of Lu Xun’s hometown that visitors are familiar with.

The memorial hall also revealed that over a hundred concerned individuals had reached out through the mayor’s hotline and inquiry numbers, urging the site to respect history and not modify the mural just because of one person’s opinion.

“It is a historical fact that Mr Lu Xun smoked; it was part of his life. Why should we change that?” — Person-in-Charge, Lu Xun Memorial Hall

The person in charge of the Lu Xun Memorial Hall told The Paper in an interview that the mural has been around for 22 years, and the memorial hall would never do anything that goes against history. The person said, “It is a historical fact that Mr Lu Xun smoked; it was part of his life. Why should we change that?”

The official response has won netizens’ support. Many commented, “This image is too classic,” and “The public isn’t so easily tempted.”

Some netizens, however, directed their criticism at Sun, accusing her of nitpicking: “Lu Xun had so many virtues, yet you only focus on his cigarette.”

Lu Xun and smoking

Lu Xun, whose real name was Zhou Shuren, was one of the key founders of modern Chinese literature, as well as a well-known social critic and intellectual enlightener. With his sharp pen, he exposed social ills and criticised feudal traditions, earning lasting respect among the Chinese people.

Historical records confirm that Lu Xun was indeed a heavy smoker, and cigarettes played an important role throughout his literary career. His partner, Xu Guangping, wrote in her memoirs that when Lu Xun was writing, he always had a cigarette in hand: “Ash would fall onto the manuscript paper, sometimes even burning small holes.”

His younger brother, Zhou Zuoren, similarly recalled in Memories of Zhitang (《知堂回想录》, Zhitang being his art name) that Lu Xun “never parted from his cigarettes, and had hardly a moment without them”.

Writer Yu Dafu, who regarded Lu Xun as both a spiritual guide and a close friend, also mentioned in Remembering Lu Xun (《回忆鲁迅》): “Lu Xun always had a heavy addiction to smoking; in Beijing, he always smoked the ten-pack cartons of the Hatamen brand.”

Such vivid recollections, passed down through time, have made smoking one of Lu Xun’s most recognisable personal traits.

Hu Baotan, author of the Shanghainese novel Alleyways (《弄堂》), said that in everyday Shanghainese, the term “old smoker” (lao yanqiang, 老烟腔) is slightly derogatory. In the new era, “new youth” should learn from and inherit Lu Xun’s spirit — not his smoking habit.

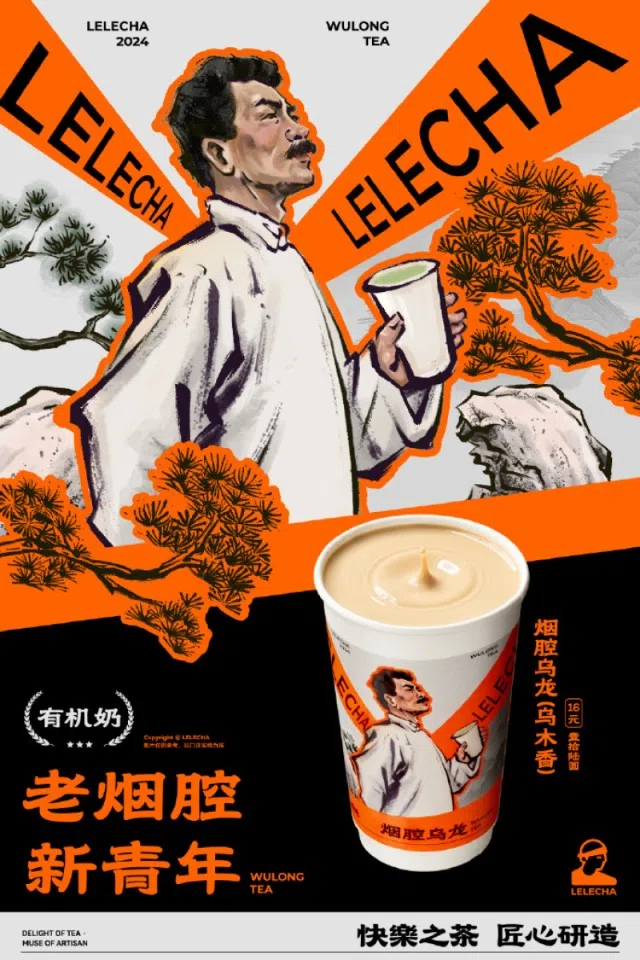

This cultural symbol has even been used commercially. In April last year, the milk-tea brand Lelecha collaborated with Yilin Publishing House to launch a co-branded drink called “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙), marketed as a tribute to Lu Xun.

Lelecha stores displayed posters featuring Lu Xun’s image, with the slogan: “Old Smoker, New Youth” (老烟腔,新青年). Customers who purchased the “Smoky Oolong” through the app would also receive Lu Xun-themed merchandise.

However, this was immediately criticised by cultural figures. Hu Baotan, author of the Shanghainese novel Alleyways (《弄堂》), said that in everyday Shanghainese, the term “old smoker” (lao yanqiang, 老烟腔) is slightly derogatory. In the new era, “new youth” should learn from and inherit Lu Xun’s spirit — not his smoking habit.

Ding Dimeng, an associate professor in the Chinese Department at Shanghai University, also commented that while deliberately using the homophone 腔 instead of 枪 added a humorous twist, promoting it in a public commercial context was inappropriate and showed a lack of respect towards Lu Xun.

In the end, Lelecha pulled the merchandise and issued an apology to Lu Xun, his relatives and the Lu Xun Culture Foundation, for “infringing upon Mr Lu Xun’s portrait rights”.

Controversy behind Sun

Sun’s complaint has sparked widespread discussion over the Lu Xun smoking mural among Chinese netizens.

Hu Xijin, former editor-in-chief of the Global Times, suggested that Sun’s complaint might have been influenced by Western baizuo (白左, white left) ideology.

In a post published on 25 August, Hu argued that Western liberals have created an ever-expanding checklist of “political correctness”, influencing Chinese public discourse.

He said, “Some people nitpick over everything, sticking moral labels onto both historical and real-life contexts. They reflect on this, reject that, and it’s become a kind of habit — finding fault with things that were once considered perfectly ordinary.”

But Hu also stressed that Sun has the right to express her opinions and should not be excessively attacked.

They questioned: if Lu Xun’s smoking image is deemed harmful to young people, does that mean the image of the poet Li Bai drinking wine should also be reexamined? And is Wu Song’s killing of a tiger in The Water Margin a violation of today’s ideas of animal protection?

Other critics argued that Sun’s complaint was divorced from its historical and cultural context, calling it an example of “false moral high ground”. They questioned: if Lu Xun’s smoking image is deemed harmful to young people, does that mean the image of the poet Li Bai drinking wine should also be reexamined? And is Wu Song’s killing of a tiger in The Water Margin a violation of today’s ideas of animal protection?

Meanwhile, some netizens discovered that Sun had repeatedly mentioned a product called “nicotine pouches” (a type of oral smokeless tobacco) on her social media. Her profile even stated: “Ultimate goal: tobacco and e-cigarettes out, only nicotine pouches allowed.”

This led to speculation about her true motives: was Sun opposing smoking out of concern for public health, or to promote nicotine pouches? Netizens mocked, “So her mouth spouts ideology, but business is where her heart is at.”

As of 26 August, Sun’s account has been deleted.

A waste of public resources?

As the controversy over Sun’s complaint continued to escalate, netizens began accusing her of “wasting public resources”. On 26 August, relevant hashtags briefly trended on China’s hot search lists.

Netizens left harsh comments such as: “Environmentalists, animal-rights people, freedom-rights people — they have nothing better to do. These are the ones truly wasting social resources.”

China’s state-run Beijing Youth Daily argued that the controversy reflects a broader issue: how to present historical symbols today. It suggested following leading museums by preserving original works while adding context through explanatory plaques.

Similarly, Beijing News came to Sun’s defence, stating that her concerns were not entirely frivolous. Especially since the “lighting a cigarette for Lu Xun” fad has triggered a wave of copycat check-ins, and Lu Xun’s smoking image has at times been trivialised or used frivolously. The article stressed the mural need not be removed, but suggested adding smoking-control guidance — such as signs discouraging cigarette use or taking “smoking selfies”.

A similar controversy happened in Singapore last year, involving a giant mural depicting a seated samsui woman holding a cigarette. Critics argued that the image was unflattering — it didn’t resemble the working women the samsui woman symbolised, but instead looked more like a prostitute. Others said that the mural glamourised smoking.

After several rounds of public debate, the authorities ultimately decided to keep the mural but add an explanatory plaque at the lower left corner. The plaque says: “The artist stresses that the cigarette depiction is not intended to glamorise or promote tobacco use. Smoking has been shown to be extremely harmful to one’s health.”

When such behaviour is depicted in public spaces, it calls for thoughtful handling — not erasure, but careful balance between historical authenticity and social responsibility.

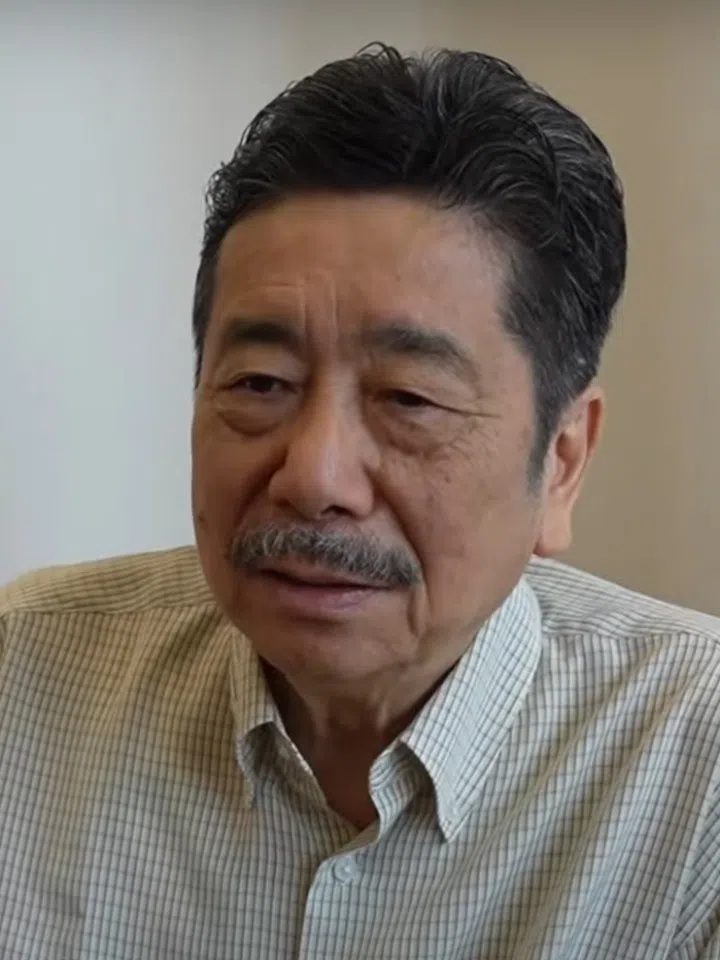

Responding to the controversy on 25 August, Zhou Lingfei — Lu Xun’s eldest grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation — recalled his own youth serving in the military, when superiors compared him to Lu Xun and pressured him into smoking, a habit he later quit. He added that now, “when I’m walking on the street and smell someone else’s secondhand smoke, I avoid it”, implying his stance against smoking.

Zhou also noted that everyone has the right to express their views, saying, “Everyone has their own sense of judgement.”

While Sun’s push to replace the mural was one-sided, the belief that “smoking is harmful to health” is a widely accepted consensus. When such behaviour is depicted in public spaces, it calls for thoughtful handling — not erasure, but careful balance between historical authenticity and social responsibility. In the end, how we engage with cultural symbols says as much about the past as it does about the society we are shaping today.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “鲁迅墙画夹烟,该掐灭吗?”.