The Slam: The Chinese wrestler who created a nation of wrestlers

China had zero wrestlers, zero rings and zero clue. Then one man called The Slam built a whole wrestling scene from scratch. Two decades later, his students run the show — and he’s still in the ring. Shanghai-based writer Kyle Muntz takes us into the world of Chinese pro wrestling.

“There was no wrestling in China 20 years ago,” says The Slam, the man universally recognised as China’s first professional wrestler. In 2004, the imposing, muscular physiques of American wrestling superstars such as The Rock, The Undertaker and Stone Cold Steve Austin had become household names. Anyone in the US would recognise the theatrical spectacle of this unique genre of performance art, where lumbering, larger-than-life giants waged pre-scripted battles of striking acrobatics — and many might even have said it was uniquely American.

But for The Slam, who would later go on to train every pro wrestler in modern China, it was not enough simply to watch occasional World Championship Wrestling (WCW) clips. “I liked wrestling too much,” says the Dongguan native — but there was no one to teach him. So in 2002, he went to Korea to study for six months, where he soon discovered he had a natural talent. “I knew how to do something just by hearing it out once, and sometimes I could even do it without the teacher telling me.”

So in the early days, they could do small shows here and there, but the audience was mostly old uncles, not sure what they were looking at.

A wrestling school in grandpa’s backyard

The Slam returned to Dongguan with a mission: “to establish an environment for professional wrestling in China”, and from these humble origins emerged his “academy”. He began by posting on the internet, attracting students from around the country and offering to teach them. Those who accepted the offer were young, “sometimes in their early 20s, but occasionally as young as 16”. And after making the pilgrimage to Dongguan, they would arrive at The Slam’s school.

“We had my grandfather’s backyard”, says The Slam, “a parking lot and his garden. So we built the ring, and things weren’t very good. At the time, there was no shelter in the backyard, so if it rained, it would hit the ring. When it rained, we couldn’t wrestle or train. Later, we built a bamboo shed, which was rainproof.”

Much of this study was extremely hands-on, with The Slam standing by to provide coaching as the young men — in plain clothes — quickly learned difficult moves on the fly.

The Slam and his “disciples” didn’t just study, they also filmed themselves and posted videos on the internet, attempting to gain a presence on then-popular Chinese social media sites such as QQ. But they soon encountered a new obstacle. “We were young and poor, in our 20s,” says The Slam. “We thought we could make money by starting a wrestling league, but we didn’t make a penny. Then, a few years later, we went to bars to play matches.”

“Problem is,” says Ho Ho Lun, China’s current world champion, “in America, everyone on the street knows wrestling. You hold an event, and they immediately want to go. But in China, nobody had any idea what this was. So in the early days, they could do small shows here and there, but the audience was mostly old uncles, not sure what they were looking at. So for a long time, it was hard to gain momentum.”

Today, The Slam reports, “Chinese wrestling has developed rapidly, and it feels like things are getting better and better. There are always shows. We used to make no money, but now a wrestler can make thousands a day.” Things are best in Guangdong, where a recent wrestling boom has led to at least one show a week.

But in the late 2000s, The Slam and his “disciples” were superstars without a spotlight. And it would take help for these performers to find their stage.

Later, Ho would found his own wrestling league, The Hong Kong Pro-Wrestling Federation (HKWF) — but first, he needed a teacher. Fortunately for him, Dongguan, where The Slam was based, was only 50 miles from Hong Kong.

Ho Ho Lun brings wrestling to Hong Kong

Today, Hong Kong native Ho Ho Lun is China’s Middle Kingdom Wrestling (MKW Belt & Road Championship) champion and also a full-time wrestler for the Japanese company Dragon’s Gate. But in the early 90s, the idea that he would someday be the victor of China’s “One Belt” would have sounded like a dream.

“There was almost nothing,” Ho says. “We got WCW, the popular American wrestling show, but it wasn’t cable TV, it was on a Japanese channel. I would watch it every month and record it on VHS. A few friends and I would watch the broadcasts and try some moves out on each other, but we didn’t know anybody else, and it wasn’t popular. For a few years wrestling was on major TV in Hong Kong; but then it stopped!”

Later, Ho would found his own wrestling league, The Hong Kong Pro-Wrestling Federation (HKWF) — but first, he needed a teacher. Fortunately for him, Dongguan, where The Slam was based, was only 50 miles from Hong Kong. Today, Ho is still only 38, but back then, he was one of those early young men discovering The Slam on the internet.

“I went to Dongguan and got slammed by The Slam”, said Ho, cracking a grin at an obviously familiar joke. “That’s how it all started.”

“There was some bamboo scaffolding on the ring”, says Ho, “and we’d practice basic moves. It was very raw, down-to-earth stuff. I don’t know how to put it in words, but whether you’re in China, Japan or America, wrestlers move in a certain way that’s internationally recognisable, so first you need to practice that. I went back and forth for a couple of years, and then it occurred to me — if The Slam could build a ring right there, maybe I could do the same thing in Hong Kong.”

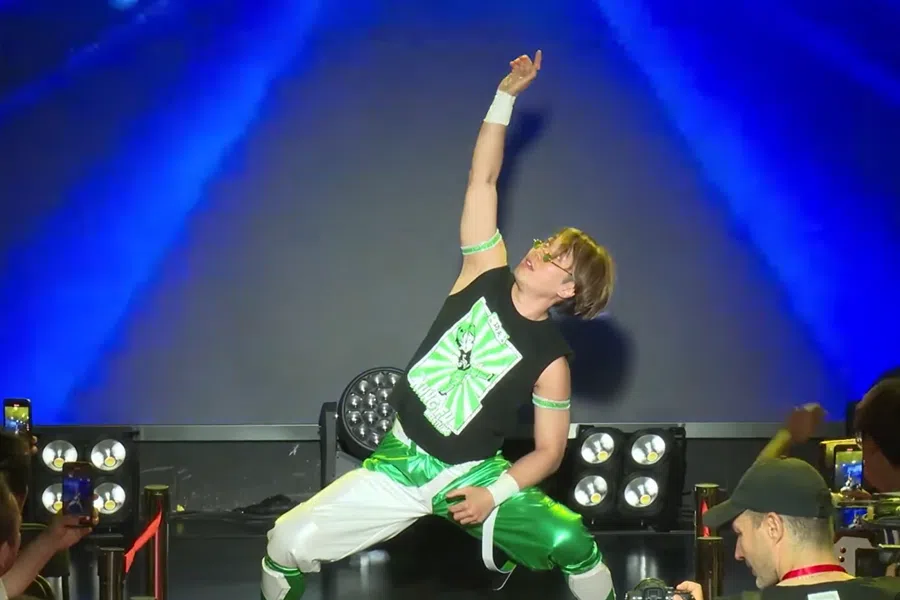

Today, despite these humble beginnings, Chinese wrestlers perform in immense, packed auditoriums amid flashing lights and the blare of rock music.

But there, too, Ho encountered the obstacle of doing something no one had dreamed of before. “I rented a warehouse in Sha Tin, and that’s where I started HKWF; but in fact, there were no wrestling ring suppliers in Hong Kong! So I went to a boxing ring supplier, and they told me they could make a wrestling ring. At that point I was like, 19 years old. I thought if somebody said they could build this thing, they must be joking. But in the end, it came — and it was a boxing ring, and they couldn’t replace it. So that’s how we started, with me getting ripped off.”

At the memory, Ho winces faintly. A normal wrestling ring, he explains, doesn’t exactly cushion the brutal falls wrestlers take so often, but “the structure of the metal bars absorbs a little of the force. I can’t say it’s no pain; it still hurts, only a little less. But a boxing ring, wow. Now that hurts. And we practiced on it for years, even after we started doing real shows in the FIFA sports center.”

The largest professional wrestling league in China

Today, despite these humble beginnings, Chinese wrestlers perform in immense, packed auditoriums amid flashing lights and the blare of rock music. “They’ve got announcers”, says Ho. “They’ve got a really nice LED screen. You come out like a superstar.”

“... the funny thing is, I don’t know how I did it. I just know it was a kind of mania. I got this idea, and I was in this fit of excitement and adrenaline, then suddenly I was telling myself: I need to find people who can build me a ring, I need to find pro wrestlers that live in China.” — Adrian Gomez, MKW founder

And much of this is the work of Adrian Gomez, founder of MKW. “15 years ago, when I moved to China, I brought my fandom with me”, says Gomez. “The first thing I did when I moved here was figure out how to watch the newest episodes of Smackdown and Raw on Youku. I’m a fan first.”

Eventually, the search for other, like-minded fans led Gomez to Renren, an online platform comparable to Facebook. In the process, he found a world of disparate fans, but no centralised platform. Wrestling had been professionalised in Japan and Korea, and occasionally companies like Dragon’s Gate might do an isolated tour, but the idea that there might be a real wrestling league in China seemed like a faint dream.

“Like, aside from what The Slam was doing in Guangdong, ‘wrestling events’ in China would be 16-year-olds in Tianjin getting together to have dinner and chat about wrestling,” says Gomez. “They knew something people on the street didn’t, so there was a lot of camaraderie. They were proud to know what wrestling was and to be into something different.”

Still, Gomez thought, the fandom was too disparate, too spread apart, too focused on things outside China rather than inside. They needed something to unify them.

“People ask me this question a lot: How did I do it?” says Gomez. “But the funny thing is, I don’t know how I did it. I just know it was a kind of mania. I got this idea, and I was in this fit of excitement and adrenaline, then suddenly I was telling myself: I need to find people who can build me a ring, I need to find pro wrestlers that live in China. I kept sending out emails, Facebook messages, QQ emails, and eventually they started pointing me towards guys like Ho Ho Lun and The Slam…and somehow…well, eventually it snowballed into all this. But in the end, I think it was that intense adrenaline that made it all work out.”

In the US, Gomez had been a volunteer for various wrestling organisations, where he helped to set up small independent shows in Arizona. In China, he found a whole new array of challenges, such as linguistic and cultural barriers. But fortunately, he soon discovered he was not alone in his excitement. “I think what people thought was, they want anybody who is willing to put in that much effort and resources into building Chinese wrestling. So they were actually quite welcoming to me, and a lot of those relationships I actually still kept with me to this day.”

... all of these wrestlers descend from the lineage birthed in The Slam’s family yard.

Still, “we were working on a shoestring budget. The referee might be a former student, and sometimes things didn’t work out quite right.” Even today, while MKW hosts countless shows with a regular roster in countless provinces throughout China, Gomez admits the challenges are not over. “We still need to be very careful not to lose money, to make every show as good as possible, because even one flop could be a big deal. We need to make sure every action we take is a deliberate step forward for Chinese wrestling.”

When asked about the future of MKW’s growth, Gomez becomes notably excited, but also moderately cautious. “I’ve got some big stuff coming—not sure I can tell you yet, but the plans are very cool. I think people are going to love them.”

Singular origin

Despite its increasing professionalism, Chinese wrestling remains uniquely connected to its past. Whether they perform for MKW or any of the newer, smaller leagues that have sprung up around China, not just some, but all of these wrestlers descend from the lineage birthed in The Slam’s family yard. And remarkably, despite The Slam’s 20 year career, even the “father” of Chinese wrestling is only 43 — a mere five years older than Ho.

“All those same guys are still active, that’s what makes this story so special”, says Ho, who recently reunited with The Slam for a climactic bout in an MKW ring to become China’s current reigning champion. “But now, they’ve finally got a place to perform.”