South China Sea: The new frontier of Sino-Indian tussle in the Himalayas?

In June 2020, the Indian and the Chinese troops engaged in one of the bloodiest skirmishes on the undefined border between the two Himalayan states. Soon after, the Indian Navy sent one of its frontline warships into the South China Sea (SCS).

The Indian move was unprecedented. Indian Navy ships have sailed through these waters to conduct naval exercises and port visits with friendly littoral states. However, never before had India deployed even a token naval presence to challenge China's sovereign claims in SCS. Even after repeated requests by the US and the other Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) countries to participate in the Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS), the Indian Navy remained focused on maintaining its presence west of Malacca. In fact, in its official doctrine, the Navy considers the SCS only as a secondary area of interest.

China's fundamental fear is the overcrowding of the SCS littorals with unfriendly navies.

The sailing of a single warship in the region cannot be construed as an act of naval coercion; it was, however, a signal of India's potential to further muddy the waters in SCS. New Delhi, Chinese analysts rightly contended, was playing the SCS card. Along with Taiwan and Tibet, the SCS forms the soft underbelly of China's sovereign anxieties in the region. Beijing has exerted administrative control over most of its claims in the SCS through its island-building spree, now fully militarised. Yet, its claims around the nine-dash lines remain contested. If external recognition is fundamental to establishing sovereign claims over territory, Beijing's gambit in these contested waters remains a work in progress.

Presence of extra-regional powers may up the stakes in SCS

China's fundamental fear is the overcrowding of the SCS littorals with unfriendly navies. First, given how cagey China is over its artificial real estate in the SCS, the presence of extra-regional powers creates a bad example for the littoral states who have been unable to stand up to Beijing's "kill the chicken to scare the monkey" type of coercive diplomacy. China fears that it may embolden the locals to challenge the uneasy status quo it has achieved through the combined application of its military power and smart but illegitimate salami-slicing tactics. Second, and more importantly, the presence of extra-regional navies leaves something to chance in the SCS. Given the rapid militarisation of the artificial islands and China's penchant for forcefully enforcing its maritime claims, the threat of accidental escalation is real.

India's actions do suggest that New Delhi may now be inclined to leverage the SCS more actively in its border strategy vis-à-vis Beijing.

The Indian Navy's intention in buzzing the Chinese was to simply convey the precarity of the latter's position in the SCS and to leverage it for negotiations on the border. A crisis between adversaries is a bargain over "power" and "resolve". If the Indian Army and the Air Force were conveying India's power on the high Himalayas, the Navy was indeed signalling its grit. Whether and to what extent India's moves in the SCS influenced the negotiations on the border is an open question, best left to the judgement of future historians. However, India's actions do suggest that New Delhi may now be inclined to leverage the SCS more actively in its border strategy vis-à-vis Beijing.

India to continue to seek leverage through SCS

Traditionally, New Delhi viewed SCS through the lens of its economic and foreign policy interests in the Indo-Pacific. More than 55% of India's seaborne trade passes through these waters. India also has stakes in the region's natural resources particularly in the oil-rich continental shelf of the coast of Vietnam. India's Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) has signed several agreements with Hanoi to explore fossil fuels in the region.

India's Act East Policy, on the other hand, aimed at balancing China's growing influence over the South East Asian region. China's rise has created economic and military pressure on the smaller states in the Indo-Pacific. India has provided economic, military, and diplomatic support to the ASEAN states. India conducts extensive military exercises in the region especially with the navies of Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, and Thailand. To Vietnam and Myanmar, India has provided military training and equipment; Singapore's armed forces regularly train in India. India maintains intense diplomatic engagement at the level of the ASEAN+6 forum, the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), and the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting (ADMM).

Finally, India remained committed to a rules-based order supporting freedom of navigation, overflight and argued for upholding the laws of the sea's convention. However, its conduct in the region was never directly related to its strategy in the Himalayas.

The Quad's greatest threat to China is the bottling up of the PLA-Navy in the SCS.

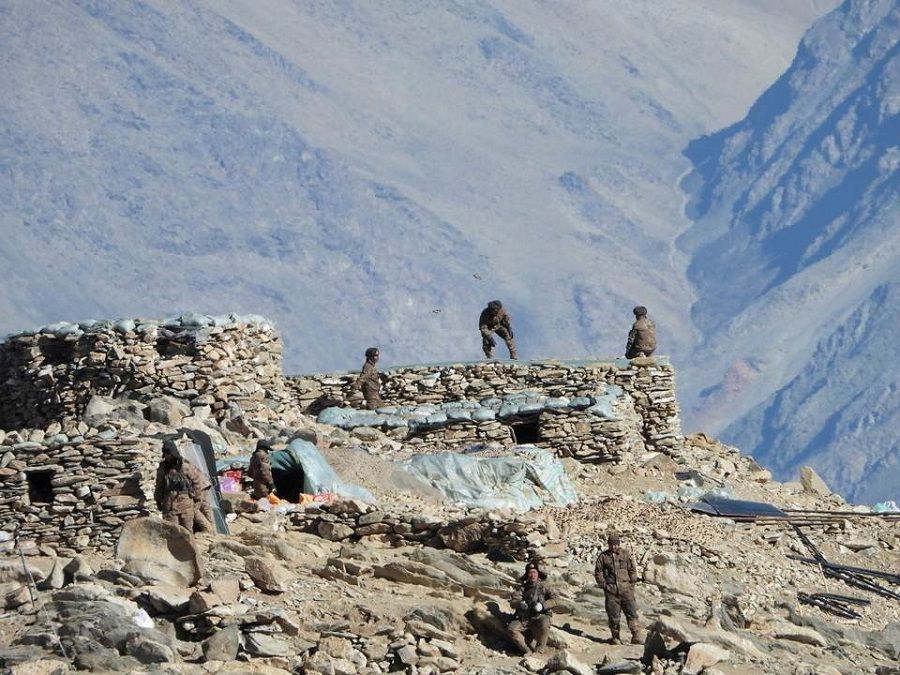

China's military pressure has forced India's hands. Given the asymmetry of military power, India is desperately searching for leverage. Military strength alone can neither deter China from initiating small-scale territorial land grabs in the Himalayas nor can it force the PLA to retreat. To influence Beijing's decision-making calculus, India, therefore, needs to exert pressure where it may hurt the most. This strategy of hurt is visible in many of New Delhi's recent decisions. First, India has strengthened its defence relationship with the US and embraced the Quad more tightly. This does play into China's fears of a larger encirclement from maritime democracies in the Indo-Pacific. The Quad's prospective containment of China is both diplomatic and physical. China may have converted the SCS into a Chinese lake, but it remains surrounded by oceans dominated by the navies of the Quad members. The Quad's greatest threat to China is the bottling up of the PLA-Navy in the SCS. The Indian Navy can play a serious role in such a containment strategy west of Malacca. Second, the Modi government believes that if China remains insensitive to India's territorial integrity and sovereignty, New Delhi must return the favour. The deployment of the Indian Navy in the SCS, employment of mountain warfare specialists drawn from the ethnic Tibetan population in the conflict with PLA, and debate over recognition of Taiwan fit the pattern.

How India calibrates its rhetoric and actions on the SCS will ultimately depend more upon Chinese actions on the border than on New Delhi's interests in the region. However, India's recent actions have shown that it has the will, if not the strength, to make China's life difficult in these waters. The SCS can be the new frontier of the Sino-Indian tussle in the high Himalayas.