Taiwan and Indo-Pacific are the primary targets of China's hypersonic glide vehicle

This August, China's Long March rocket carried a hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) into lower space orbit. Once the Long March rocket reached the lower earth orbit in outer space, it launched an HGV which orbited around the earth before gliding to its target in the Pacific Ocean at supersonic speeds. This fractional orbital bombardment system (FOBS), now mastered by China, has left the US stunned.

China's ballistic missiles such as DF-26 or DF-31 home in on their target via the North Pole and thus face the full wrath of American missile defence systems. The HGV, however, can orbit the outer atmosphere and attack via the South Pole, rendering northward-facing defensive measures wholly inadequate.

A US Congressional research report released in October 2021 argued that China may now have a "space-based global strike capability". General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the US military, has called it the 21st century "Sputnik moment" for American decision makers.

The elements of speed, manoeuvrability and surprise, therefore, make HGVs extremely lethal.

Disruptive to nuclear stability?

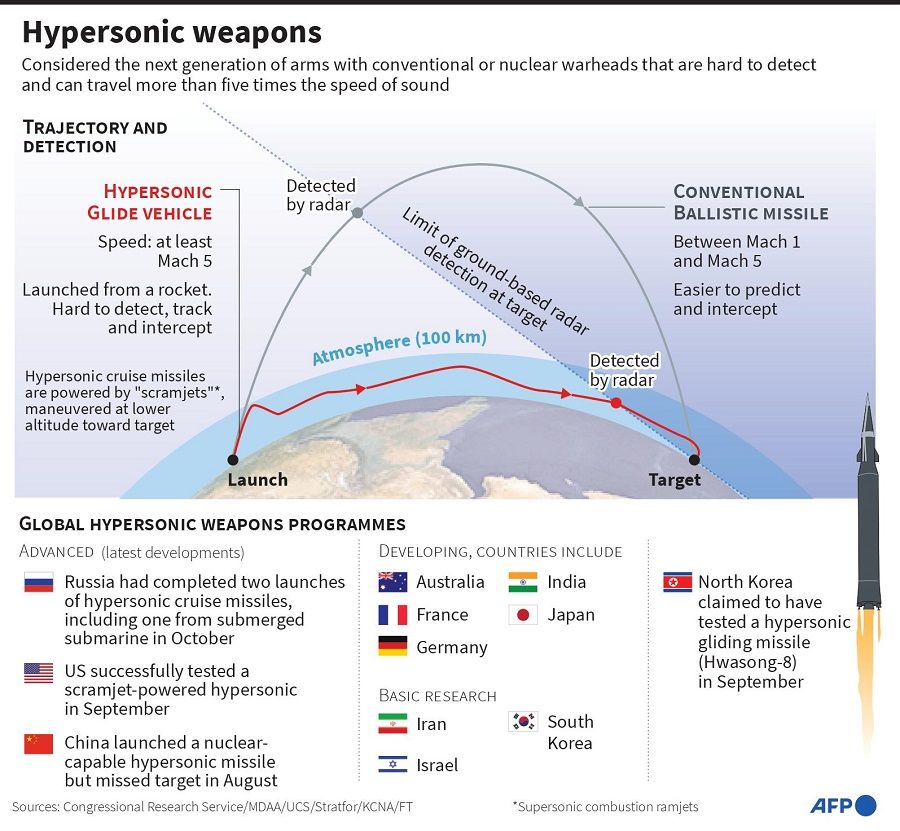

HGVs outperform the traditional means of nuclear weapons delivery performed by ballistic missiles in several ways. First, HGVs can travel at breakneck speeds ranging from Mach 5 to Mach 20. Such superfast velocities leave very little time for the targeted state to respond to any surprise attacks.

Second, unlike ballistic missiles, HGVs high manoeuvrability allows them to escape defensive countermeasures such as ballistic missile defences of the adversary.

Lastly, HGVs fly at depressed trajectories, rendering their early detection from ground-based radars as well as space-based sensors extremely difficult. The elements of speed, manoeuvrability and surprise, therefore, make HGVs extremely lethal.

HGVs are part and parcel of what strategic thinkers call disruptive technologies: emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, cyber weapons, space-based weapon systems, which may upset the mutual vulnerability engendered by the balance of nuclear terror among nuclear-weapon states.

The Cold War strategic stability was predicated on the belief that all nuclear-armed states can inflict disproportionate harm upon each other. Therefore, the mere existence of nuclear weapons ensured their non-use and thwarted conventional wars between nuclear-armed adversaries for fear of escalation to nuclear levels.

Making China's nuclear deterrent more credible

Rather than being disruptive to nuclear stability, Beijing, however, views HGVs as central to maintaining the credibility of its nuclear deterrent. Firstly, Beijing's policy of "no first use" of atomic weapons and its comparatively small nuclear arsenal renders it vulnerable to an American nuclear first strike. China's vulnerability is compounded by the growing American capability to counter China's nuclear retaliatory power through missile defences. Such missile defence systems are not only located in North America, but in the last decade, the US has emplaced parts of them in South Korea and Japan. The geographical proximity of American missile defence systems may lead to early detection and destruction of China's retaliatory nuclear strikes. Such nuclear vulnerability also accounts for China's expanding nuclear arsenal and its attempts to make its nuclear weapons more survivable.

Second, fear of atomic coercion notwithstanding, Beijing feels equally threatened by the US capability to conduct precision strikes through advanced conventional weapons such as cruise missiles and stealth bombers. America's Conventional Global Prompt Strike (CGSP) programme, initiated in 2002 under President George W. Bush, has matured to a level that the US may not need nuclear weapons to target Chinese nuclear or conventional military assets. HGVs constitute a Chinese response to what decision makers consider a growing military vulnerability.

HGVs also signal to states in the Indo-Pacific region that if need be, China can effectively target territories of all American allies in the area.

Presenting more of a threat vis-à-vis Taiwan and the Indo Pacific

However, Beijing's calculations are equally inspired by its immediate requirements in the Indo-Pacific, such as establishing its military primacy in the region, including a possible forceful occupation of Taiwan, and forcing American allies to reconsider their growing military cooperation with Washington. First, Chinese decision makers would have to countenance the threat of direct US intervention in any conflict scenario over Taiwan. Raising the costs of US involvement, therefore, remains China's top priority. Successful mastering of HGV technology not only blunts American nuclear edge over China (which may be employed to pressure Beijing during any cross-strait crisis) but can also carry conventional warheads, can be used in support to destroy and deter American aircraft carriers and military bases in the Indo-Pacific.

In the event of a crisis over Taiwan, Beijing only needs to create doubt, both in Taiwan and in the minds of American decision makers, that any resistance to Chinese actions would be highly costly. Second, HGVs also signal to states in the Indo-Pacific region that if need be, China can effectively target territories of all American allies in the area. China's technological march over the US - especially in the FOBS system as demonstrated by China's HGV test - may create a crisis of confidence among US allies. This objective has become far more central to China's strategy in the aftermath of AUKUS and the recent ramping up of cooperation among the Quad countries.

However, Beijing's calculations may unravel difficulties in the long term. First, it will engender tremendous effort in the US to undertake robust defensive measures against China's HGV programme. The US Department of Defense has already started funding and research on hypersonic defences, including work on space-based low-earth-orbit sensors for early detection of hypersonic launches. China's technological march will undoubtedly lead to further concentration of American scientific and technical resources. China is already facing the brunt of competition and technology denial, such as in the case of Huawei and 5G.

A lack of allies in the Indo-Pacific is China's most significant vulnerability.

Second, it may also prod countries like India, Japan, and Australia to acquire hypersonic weapons. Thus, China will have to compete with the US and other major powers in the Indo-Pacific. A lack of allies in the Indo-Pacific is China's most significant vulnerability; rather than leaving the American coattails, China's military capabilities will force these countries to embrace them more tightly. An increased presence of US missile defence systems in the Indo-Pacific may be the natural outcome.

Sputnik moment or not, what is evident is that a genuinely 21st century arms race is now underway. The principal target of this military technological competition is the Sino-American contest over the Indo-Pacific.

Related: China displays its new weapons amid cross-strait tensions | Chinese academic: China will pay the price for underestimating the US | The Indo-Pacific strategy could turn into an empty shell under Biden | More mainland Chinese elites supporting armed unification with Taiwan: A cause for concern? | The US has AUKUS. Where are China's alliances? | With AUKUS in place, now what for key players in the Indo-Pacific?