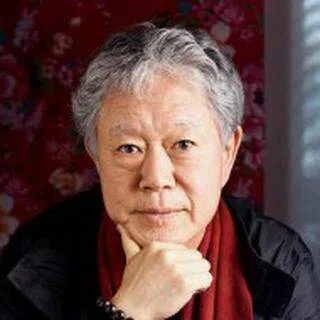

Taiwanese art historian: The five elements of cooking in the olden days

Being his mother's good helper in the kitchen for many years, Taiwanese art historian Chiang Hsun got to experience cooking with firewood, charcoal and of course the everyday natural gas. He is convinced that a different fire and stove begets a different flavour in food. Taiwan today is fortunate to have access to fire at the flick of a switch but this could all change. Lucky thing for Chiang, some firewood is all he needs to make his favourite scorched rice snack.

Mother's cooking taught me many things, such as how to work with material objects. I befriended firewood and an iron wok and learnt how a fire lights up in an earthen stove. I got to know how to steam a bun over boiling water.

Perhaps I should first explain that the implements used back then were different from what they are today.

Based on the theory of the Five Elements (五行 wuxing: Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal and Water), kitchens then all had an earthen stove (Earth) that used firewood (Wood). My siblings and I would help Mother start the fire when she cooked. First, we used thin tree branches as kindling, then lit balls of newspaper to get some embers going before adding the thicker branches.

Survival skills

Because of Taiwan's humidity, it was difficult to burn firewood. We often had to dry the wood under the sun during the day. We learnt that dry firewood made the biggest fires (干柴烈火, an idiom describing lustful relationships between men and women) as we got acquainted with firewood and fire. In the process, we learnt about our own and other people's desires.

... black smoke would billow from every household when it was time to cook. I'll always be grateful for the woody scents that the trees rewarded the world with.

If you used damp firewood, there would be clouds of black smoke, your eyes would burn and your face would be covered in soot. Thus, at mealtimes, families would move the stove to the back alley where there was more ventilation. The smoke wouldn't get into the house, and the fire would be stronger with more oxygen from the air.

We only added charcoal to firewood after the fire got going as charcoal was expensive even though it produced less smoke. Most families used raw coal, and black smoke would billow from every household when it was time to cook. I'll always be grateful for the woody scents that the trees rewarded the world with.

It wasn't easy to cook over a charcoal stove. While heat can be easily adjusted on your modern gas burner, how do you control the flame of a charcoal stove?

If we needed the fire to be stronger, we would open the door and fan the flames. Later in life, that's how I was able to identify the people who often "fanned the flames" of a situation.

Every charcoal stove comes with a door about the size of a fist. Those made with iron sheets were easy to open and close. I remember the earliest stove door we had was made of clay. Once, the door broke and Mother asked me to get some discarded hair from the barber shop, mix it with wet clay, and use it to patch up the door for the time being.

If we needed the fire to be stronger, we would open the door and fan the flames. Later in life, that's how I was able to identify the people who often "fanned the flames" of a situation.

Chinese folk vocabulary and idioms often come from life lessons, which is a very different thought process from how intellectuals prepare for their examinations.

Cooking was tough back then. When the water starts to boil and spills out of the wok, the stove door has to be almost closed but the fire shouldn't go out. With a gentle wind and a little air to keep the little fire burning, the rice slowly gets cooked, emitting an array of fragrances at different temperatures. The wok must also be jiggled at all times so that the heat is evenly distributed. When a faint charred scent is detected, that's when the rice is cooked. A layer of golden brown scorched rice would form at the bottom - that's my absolute favourite. I would often leave the wok on the stove for a little while longer just to make more scorched rice.

Scorched rice is so delicious because of its fragrance and chewy texture. Those with good teeth would naturally love the crunchiness of scorched rice.

The good old days

Humans have lived for tens of thousands of years without gas and electric cookers and I was lucky enough to have experienced the tail end of those years. While that generation of people (including myself) is envious of the people with access to gas and electric cookers, I don't agree that one cannot live without gas and electric cookers because we have once used firewood and charcoal to cook rice in a huge iron wok.

The history of Taiwan's domestic fuel consumption is worth studying. Firewood and charcoal were used in the 1950s, foreign oil was used later on, while charcoal briquettes (煤球) were used for a long time.

In Taiwanese, charcoal briquettes are called "charcoal balls" (炭圆) or "charcoal pellets" (炭丸), which are made by mixing coal cinders with soil. They produce a pungent smoke when burnt, with black ashes flying everywhere.

The Chinese character for "home" (家 jia) is a pictogram of "pigs" (猪 zhu) reared under one roof. The home I remember is one with a stove that always stays warm.

Charcoal briquettes are probably something I remember from the 1960s. There were long rows of charcoal briquettes piled up in the corners of every house. Each briquette was roughly 15 centimetres long, round and with a hole in the centre. When we used briquettes, we still needed to light a fire first, but the good thing is that briquettes can be swapped out with another one without relighting the fire. This made it much more convenient.

Briquette stoves came with doors as well. After dinner was served and the stove door was shut, an iron kettle was left on the warm stove, so that we could always have some warm water to drink.

The Chinese character for "home" (家 jia) is a pictogram of "pigs" (猪 zhu) reared under one roof. The home I remember is one with a stove that always stays warm.

Used charcoal briquettes were mostly used to fill road potholes later on. Back then, roads were unpaved and without asphalt. It often got muddy when it rained, creating more potholes, which would then be filled with briquettes that had served their purpose.

During the anti-Communist and anti-Russian era, scorched rice was drizzled with a variety of toppings which came with the aptly political name "Bombing Moscow". I guess this is something that the people with voting rights today do not know about.

Food flavours change with the type of fire and stove

There I was wanting to share about Mother's cooking, and now I've gone on about domestic fuels...

I have always thought that the same dishes cooked over different fires and stoves have a different taste. From firewood to charcoal, I remember the sweet scent of acacia and longan wood over the fire, the crackling sound they made when they were reduced to ashes and the black marks they left on our iron wok.

The scorched rice dishes I remember are mostly from my memories of the time when firewood and charcoal were used. During the anti-Communist and anti-Russian era, scorched rice was drizzled with a variety of toppings which came with the aptly political name "Bombing Moscow". I guess this is something that the people with voting rights today do not know about.

Could taking things for granted become humanity's biggest crisis?

The period when gas was first used in regular Taiwanese households perhaps marks a major revolution in food history. When Russia invaded Ukraine, some commentators analysed Europe's scramble for natural gas. That was when I realised that the natural gas we take for granted today could be gone one day.

Fuel for the fire - whether from firewood, charcoal, oil or natural gas - how will it affect my life?

Could taking things for granted become humanity's biggest crisis?

Cooking can't be delinked from fire and water. But today, Taiwan has also taken tap water for granted. There wasn't tap water during my childhood days and we washed our clothes and vegetables by the streams. We also drew water for cooking from the nearby well. These were also done as a matter of course.

... a real change of era happens when the daily lives of the common people are transformed. It has nothing to do with the so-called "major events" that history loves to exaggerate.

Using firewood (Wood), water from the streams (Water), charcoal fire (Fire), iron woks (Metal) and earthen stoves (Earth), I returned to the era of Mother's cooking and was reminded of the Five Elements in her life again.

The first electric cooker appeared in Taiwan in 1960, completely changing the way people cooked rice. With the advent of electric cookers, the joy and happiness of the entire family and neighbourhood was indescribable. When you reach a certain age, you would understand that a real change of era happens when the daily lives of the common people are transformed. It has nothing to do with the so-called "major events" that history loves to exaggerate.

Recently, a friend of mine wanted to eat scorched rice so badly that he tried to cook rice over firewood. But he filled the house with smoke and covered his face in soot. He even got a scolding from his wife...

This article was first published in Chinese on United Daily News as "五行 九宮 蔬食2".

Related: Life and life lessons in the old markets of Taiwan | Taiwanese art historian: My mother waited for her soldier husband to return from war, just like Wang Baochuan | Taiwanese art historian: How should I meet my mother in the afterlife - as a child, an adult or an old man? | Taiwanese art historian: What my father taught me | Remembering a mother's beautiful smile and Suzhou's 'Sixth Moon yellow' crabs