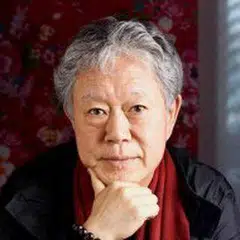

Taiwanese art historian: Reflecting on the indigenous culture of Orchid Island

It was the first time I saw a Calophyllum blancoi (blancoi) tree in bloom. Ivory white flower buds adorned the tree: when closed, the buds looked like beads of jasmine; when in bloom, the petals revealed their bright gold stamens, like white jade inlaid with gold threads - a magnificent and precious sight.

The blancoi is native to Taiwan's Orchid Island (兰屿) and Green Island (绿岛), and the Luzon Island in the Philippines. It seems to be an endemic species in the southern regions. While there are people researching and cultivating the plant in Taiwan, it is seldom seen. I saw the blooming blancoi at Taitung's National Beinan Archeological Site and especially cherished the experience.

In the 1970s, my visit to Orchid Island stirred up all sorts of feelings in me. The beautiful ocean, lush forests, gorgeous ipanitika (traditional fishing boats of the Tao (Yami) people of Orchid Island) and melodious ritual songs surrounded me, but I stayed at a hotel run by the Han Chinese.

I saw many little children of the Tao people peering into the hotel through the floor-to-ceiling window, but they were not allowed to enter. I walked outside to play with them, and read the name tags on their school uniform: "Hsieh..., Hsieh..."

I asked, "All of you have the surname 'Hsieh', are you from the same family?"

Staying at a Han Chinese-run hotel, a thin veil of translucent glass separated me from the outside world. I was probably ignorant enough to think that these children should most certainly use Han Chinese surnames.

The blancoi does not seem to be a botanical species of Taiwan. It could be linked to Luzon Island or the vast waters of the southern islands.

Over the years, I have been reading the books of Tao writer Syaman Rapongan. Although he writes in Chinese, his words tell the survival stories of Tao, an independent and autonomous maritime tribe.

The name of his firstborn is "Rapongan" and he is the child's "father" (Syaman). Because parents are named after their children in Tao culture, his name becomes "Syaman Rapongan" (father of Rapongan).

In a world of diverse cultures, how can we learn to respect the dignity of each entity as an independent and autonomous being, and respect these differences?

The children of the Tao tribe need not bear the surname "Hsieh" anymore. They can be called "Rapongan" when they are little and "Syaman" when they become a father - such a naming convention is significant and is part of the belief system of their unique heritage.

I pondered over the fact that he wrote about the stories of his own tribe using the characters of a "foreign tribe".

But does the world work the way we want it to?

Boatloads of African slaves were once sold and have become the "Mary", "John", "David" or "Babara" of today. The rules of the game between the strong and the weak will ultimately say: "Decide for yourself..."

Some of their offspring will say, "I choose to be called 'John'." The children of the Tao people may say, "I don't want the surname Hsieh."

I pored over the words of Syaman Rapongan. I pondered over the fact that he wrote about the stories of his own tribe using the characters of a "foreign tribe". Although the size of his tribe is 2,000 to 3,000 people, I deeply admire and respect the survival stories of these people.

The Tao people use the trunk of the blancoi to build the pillars of their houses and sometimes their ipanitika as well. The strong wood shelters them from the wind and rain, and also allows them to sail the seas, so Syaman can always point out the stars in the vast sky above to his children - stars that look as beautiful as the blooming blancoi.

Related: Taiwanese art historian: What flowers and swallows taught me about life amid the pandemic | Taiwanese art historian: 'Lord of the banyan tree' and his grand wisdom | A tree can be like Buddha | What I Ching and the mangrove tree flowers tell us about life | A return to the physical body and the exuberance of the Tang dynasty