[Big read] Can Southeast Asia challenge China’s dominance in mature chips?

With Southeast Asia already a major chip packaging and testing hub, will the region be able to rally together to move up the value chain to compete with global chip manufacturers? Lianhe Zaobao journalist Tobby Siew speaks with industry analysts to find out.

In recent years, global semiconductor giants have flocked to Southeast Asia for investment opportunities, signalling that the region’s chip manufacturing industry is on the cusp of a breakthrough.

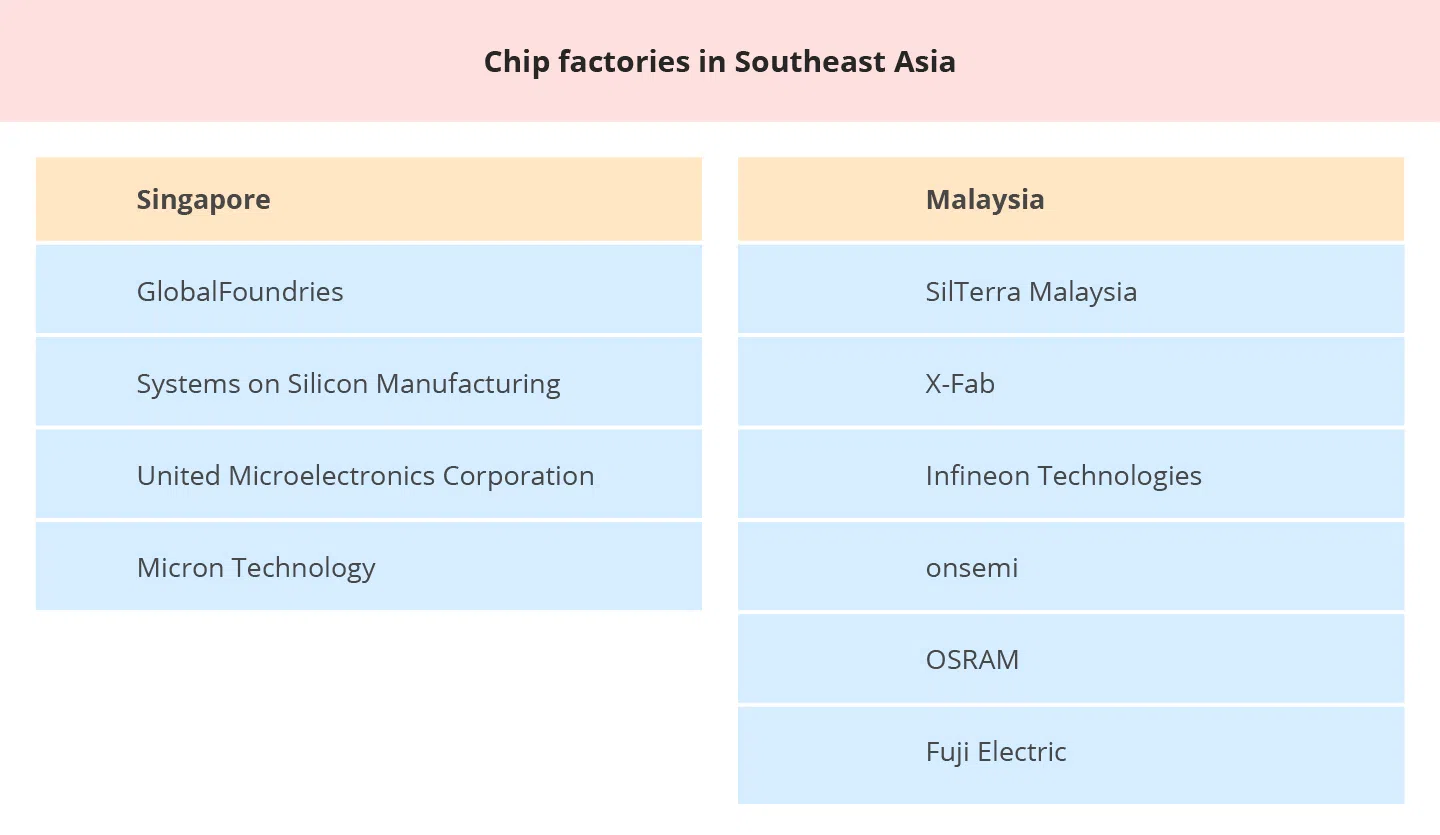

In April this year, United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC), one of the top five global semiconductor foundries, opened a new chip plant in Singapore. Once the plant is fully operational, the manufacturer is expected to step up its annual capacity by nearly 50% to produce one million wafers. This marks the first time UMC has expanded its capacity in Singapore since it first set up shop in 2001.

In June 2024, Vanguard International Semiconductor Corporation, backed by the global semiconductor foundry leader Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), teamed up with NXP Semiconductors to invest US$7.8 billion to build a wafer plant in Singapore.

Going further back, GlobalFoundries, another global semiconductor foundry bigwig, announced in 2021 an investment of US$4 billion to establish a 12-inch wafer plant in Singapore, which commenced operations in September 2023.

Surge in chip plant investments in Southeast Asia

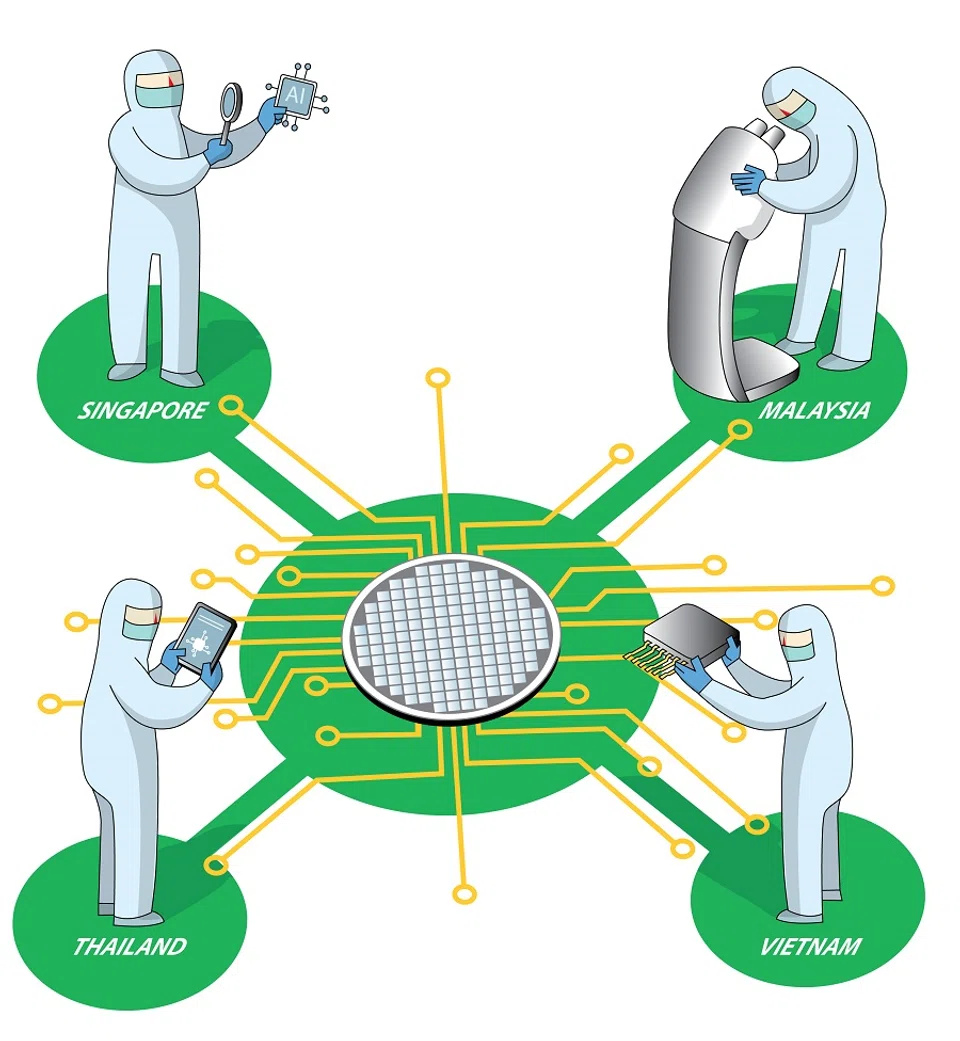

This wave of chip plant investments has also reached other Southeast Asian economies.

In neighbouring Malaysia, German semiconductor giant Infineon announced in August 2023 a significant expansion of its facilities in the country, to build the world’s largest 8-inch silicon carbide (SiC) power wafer plant.

The Vietnamese government is also keeping pace; in March this year, it approved a nearly 13 trillion dong (approximately US$501 million) wafer plant construction project. Potential investors include GlobalFoundries as well as Taiwan’s Powerchip Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp, with the plant expected to be ready by 2030. This will be Vietnam’s first wafer plant, marking a huge breakthrough in its semiconductor strategy.

Southeast Asia accounted for nearly 20% of global packaging and testing capacity in 2022. By 2032, the region’s market share in this sector is expected to grow to 27%.

Thailand, known as the “Detroit of the East”, is also an active player in this field. Last year, it announced an investment of 11.5 billion baht (approximately US$350 million) to construct the country’s first SiC chip factory, which is expected to begin production in Q1 2027, primarily serving growth in electric vehicles (EVs) and data centres.

Efforts to move upstream

The semiconductor industry broadly consists of three major segments: upstream chip design, midstream chip manufacturing and downstream chip assembly, testing and packaging (ATP). Southeast Asia has traditionally excelled in the downstream chip packaging and testing segment.

According to a joint report by the Semiconductor Industry Association (SEMI) and Boston Consulting Group, Southeast Asia accounted for nearly 20% of global packaging and testing capacity in 2022. By 2032, the region’s market share in this sector is expected to grow to 27%.

The aforementioned chip plant investment projects reflect Southeast Asia’s efforts to move upstream and gain a foothold in the chip manufacturing sector, which had traditionally been dominated by Taiwan, South Korea and mainland China.

The semiconductor value chain becomes more attractive as one moves further upstream. According to Topsperity Securities, the ATP segment accounts for only 6% of the total value; in contrast, the manufacturing segment contributes 19%. Collectively, chip design, electronic design automation and intellectual property account for nearly 60% of the total value.

Linda Tan, president of SEMI Southeast Asia, told Lianhe Zaobao that spurred on by artificial intelligence, EVs, industrial automation and edge computing, the global semiconductor market is expected to reach nearly US$1 trillion by 2030.

She said, “For Southeast Asian economies, this is an extremely attractive business opportunity. Developing the chip manufacturing industry would not only spearhead industrial transformation, it also creates high-quality and high-paying job opportunities”.

... the US is targeting the production of advanced chips 10 nm and below, while Southeast Asia focuses on mature processes, thus there is no direct competition between the two in terms of technology. — Helen Chiang, Asia Semiconductor Reseach Lead, International Data Corporation (IDC)

The US, which used to be the hub for semiconductor manufacturing, is also ramping up investment to attract semiconductor giants to set up or return to the US. Since the passing of the CHIPS Act, the country has attracted over US$100 billion in investments. This included TSMC’s announcement in March this year of US$100 billion on top of its existing US$65 billion investment. US semiconductor manufacturing giant Intel also announced plans to invest US$100 billion to expand or build new plants in four US states.

Would the US’s bid to attract investment result in reduced investments for Southeast Asia’s chip manufacturing industry?

Helen Chiang, Asia semiconductor reseach lead at International Data Corporation (IDC), said that the US is targeting the production of advanced chips 10 nm and below, while Southeast Asia focuses on mature processes, thus there is no direct competition between the two in terms of technology.

Major companies diversifying supply chains

In terms of technological ambitions, Southeast Asia is not pushing to fulfil its chip industry dreams; however, the region’s efforts to build chip plants are closely tied to national strategy and security.

Digitimes Research analyst Eric Chen told Lianhe Zaobao that with rising geopolitical tensions, the risk of semiconductor supply chain disruptions is increasing. Hence, Southeast Asia would naturally want to set up more chip plants in the region; this would help avoid a chip shortage if geopolitical conflicts were to intensify.

Chen said, “Each country is worried about supply disruption risks, which is why everyone hopes to manufacture chips themselves to avoid being completely dependent on external sources.”

In fact, various global and regional events over the past decade have inadvertently pushed Southeast Asia forward. First, the Covid-19 pandemic that broke out in 2020 made semiconductor giants aware of how fragile the chip supply chain was.

... pressed by clients, more semiconductor companies are proposing “mainland China plus one” or “Taiwan plus one” strategies — in other words, establishing chip plants outside of these two economies. — Chiang

According to a survey by consulting firm McKinsey and Company in Q2 2020, as many as 93% of companies planned to enhance the resilience of their supply chains post-pandemic, including expanding capacity to other economies within their region — even extending to other regions.

“After the impact of the pandemic, global semiconductor bigwigs began to reassess the fact that their capacities were overly concentrated in a small number of countries,” Chen said.

The intensification of geopolitical tensions, especially the Taiwan Strait crisis and the escalating US-China rivalry, further heightened the urgency of supply chain diversification. IDC’s Chiang revealed that, pressed by clients, more semiconductor companies are proposing “mainland China plus one” or “Taiwan plus one” strategies — in other words, establishing chip plants outside of these two economies.

Against this backdrop, Southeast Asia, with several advantages, has become a favourite of many semiconductor giants. SEMI’s Tan pointed out that in addition to a comparatively neutral geopolitical stance, Southeast Asia also benefited from a solid semiconductor industry foundation. “For instance, Malaysia has laid a solid foundation in the ATP segment, and continues to attract major semiconductor equipment manufacturers. Meanwhile, Singapore has achieved commendable results in the chip design and manufacturing segments,” she said.

“Vietnam and Thailand are also working hard to enhance their domestic infrastructure to attract more investments,” Tan added.

Chiang also highlighted that compared with other Southeast Asian economies, Singapore has relatively abundant technical talent as well as stable water and electricity supply, thus propping up the chip manufacturing segment. “Hence, it’s understandable why foundries such as GlobalFoundries and UMC would prioritise Singapore, “ she said.

China’s aggressive capacity expansion ignites price war

Due to simultaneous capacity expansions by other economies or regions, Southeast Asia’s path to upgrading its semiconductor industry is bound to be fraught with challenges.

After the US launched a tech and chip war to limit China’s advanced chips production, China chose to focus on producing mature chips 22 nm and above. This posed a tough challenge for Southeast Asia’s chip manufacturing plans.

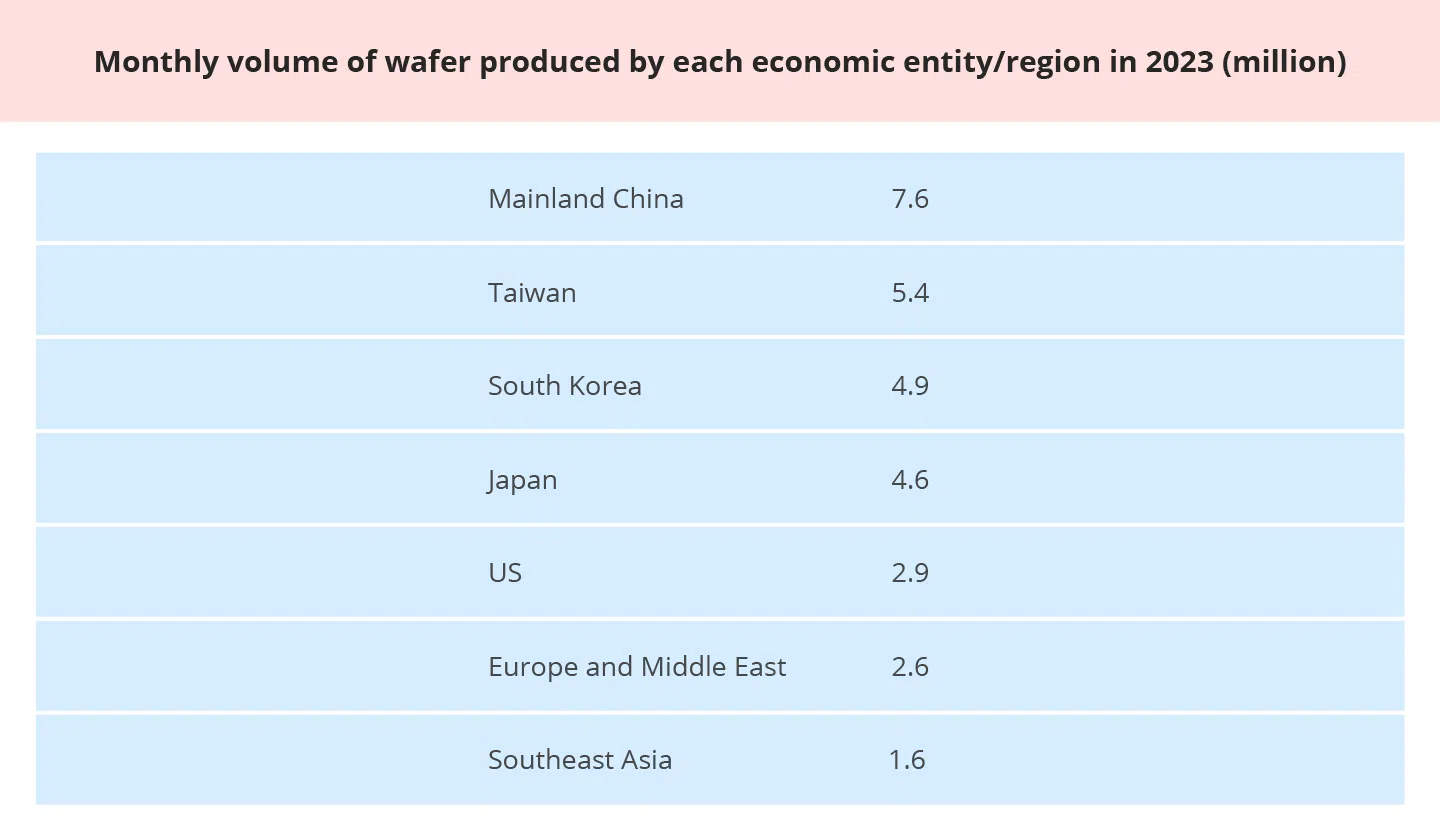

IDC estimated that China’s market share in global mature chips would reach 28% this year, and reach 39% by 2027.

Chinese semiconductor foundry giants Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation and Huahong Group are expanding their capacities for 28- to 22-nm mature chips this year, while Nexchip would expand its 55- to 40-nm chips.

Huatai Securities predicted that between 2024 and 2027, China’s mature chip capacity would see an average annual growth rate of 27%. IDC estimated that China’s market share in global mature chips would reach 28% this year, and reach 39% by 2027.

The expansion of China’s capacity is accompanied by a brutal price war. In a report published in February, Nikkei Asia quoted an informed source who commented that while renowned US semiconductor manufacturer Wolfspeed sells its 6-inch SiC wafers for US$1,500 each, Chinese suppliers offer them at a price as low as US$500 — or even lower.

Chiang stated, “Backed by government incentives, Chinese chip manufacturers are expanding their mature chip capacities. This places tremendous pressure on wafer prices and the Southeast Asian chip manufacturing industry, which is seeing its space to compete being restricted”.

Oversupply of mature chips

In addition to China, South Asian giant India has also made significant strides.

India launched the India Semiconductor Mission in December 2021 to build a self-sufficient chip ecosystem. On 14 May this year, the Indian government approved a semiconductor plant to be jointly established by Foxconn and India’s HCL Group, to produce chips for mobile phones, computers, automobile systems and more.

Europe, once a global chip manufacturing stronghold, has also taken various measures to regain its former glory. The European Commission proposed the European Chips Act in 2022 to strengthen Europe’s chip research and production capabilities, looking to capture 20% of global chip production by 2030.

With EU subsidies, TSMC has also teamed up with European semiconductor companies to build a 12-inch wafer plant in Germany, expected to start production in 2027.

“Various economies are still greatly increasing chip supply, thus putting Southeast Asia’s chip manufacturing industry in a bind.” — Eric Chen, Analyst, Digitimes Research

Digitimes’ Chen commented that these developments reflect that, in addition to being a driving force for industrial development, various economies also view the chip manufacturing industry as a part of national security. “To avoid being constricted by foreign countries, everyone would rather take on the risk of oversupply and invest in building chip plants,” he said.

He observed that since the end of the pandemic, demand for mobile phones and computers has been lacklustre, resulting in limited demand and sales growth for mature chips. “Various economies are still greatly increasing chip supply, thus putting Southeast Asia’s chip manufacturing industry in a bind,” he added.

IDC’s Chiang echoed a similar view, noting that mature chips have already fallen into an oversupply. “Under constant pricing pressure, the Southeast Asian chip sector is set to face challenges,” she said.

Experts: Southeast Asia should ‘rally together’ to expand market pie

Under siege by various economies or regions, how can Southeast Asia’s chip manufacturing industry achieve a breakthrough?

Those interviewed would say to “rally together”.

Chiang felt that Southeast Asian countries should establish deeper trade and economic cooperation to jointly expand the market pie.

Chen agreed, adding that the market scale of any Southeast Asian economy by itself would be insufficient to sustain its domestic chip plants, so deepening trade relations with regional partners and expanding domestic chip exports is necessary.

“As no Southeast Asian country on its own has a market scale on par with China or India, deepening regional alliances is the only option.” — Chen

He said, “Whether the chip manufacturing industry can succeed or attract foreign investment is largely dependent on market demand. China and India have tremendous potential, due to their populations exceeding 1.4 billion each. Even if only half of the population has purchasing power, it is a big enough domestic market to prop up its chip manufacturing industry.

“As no Southeast Asian country on its own has a market scale on par with China or India, deepening regional alliances is the only option.”

In other words, in the process of developing the chip manufacturing industry, Southeast Asian countries are not only competitors — they also have opportunities for cooperation or partnerships among themselves.

A series of events in recent years also reflected the strong demand for chips in Southeast Asia, benefiting the region’s chip exports. For example, in April 2024, Malaysia established the largest integrated circuit design park in Southeast Asia in Selangor.

Selangor Information Technology and Digital Economy Corporation (SIDEC), the project’s execution unit, revealed that due to Malaysia’s lack of wafer foundries, chip design firms in the park could place orders with chip plants in Singapore.

Moreover, Southeast Asia’s constant attraction of data centre project investments also created opportunities for the regional chip manufacturing industry. This is because each server requires dozens of chips, including for central processing units and memory storage chips.

Thailand and Malaysia’s booming EV investment projects are also another shot in the arm for Southeast Asia’s chip manufacturing industry.

In the first ten months of 2024, Malaysia attracted 141.7 billion ringgit (US$33.3 billion) in data centre investments, soaring more than threefold year-on-year, making it a regional data centre hub. Investment bank and consulting firm ARC Group estimated that between 2023 and 2029, Southeast Asia’s data centre investment would experience a compound annual growth rate of 9.59%.

Thailand and Malaysia’s booming EV investment projects are also another shot in the arm for Southeast Asia’s chip manufacturing industry. A combustion engine vehicle typically contains around 600 chips, while an EV requires around 1,600 chips.

According to a report released by investment companies Temasek and LeapFrog in September 2024, Southeast Asia is expected to see US$365 billion in EV project investments by 2030.

Can Southeast Asia produce chips below 10 nm?

Existing wafer plants in Southeast Asia focus on mature chips. For instance, in Singapore, GlobalFoundries’ plant focuses on 130- to 40-nm processes, while UMC’s new plant focuses on 28- to 22-nm processes. Most wafer plants in Malaysia focus on processes above 100 nm.

Is it possible for Southeast Asia to develop plants for advanced chips 10 nm and below the likes of TSMC or Samsung Electronics, or attract related investments?

IDC’s Chiang believed this is challenging because the technical talent, equipment and costs required for advanced chip plants differ significantly from those for processes 20 nm and above.

... if Southeast Asia wants to upgrade to advanced processes, aside from cost and talent issues, it would also need to consider demand. — Chen

According to Digitimes Research, the construction costs for plants manufacturing chips from the 90- to 20-nm range would cost US$2 billion to US$9 billion. However, for a 14-nm chip plant, cost would rise to US$10 billion, and for a 5-nm plant, cost would soar to US$16 billion.

Digitimes’ Chen pointed out that if Southeast Asia wants to upgrade to advanced processes, aside from cost and talent issues, it would also need to consider demand. Advanced chip manufacturers decide whether to invest based on whether there are local customers placing orders, as well as the volume of those orders, among other factors.

He added, “After all, an advanced chip plant costs more than US$10 billion, and that’s not including operating costs. If the order volume is not enticing, advanced chip plants naturally have no reason to invest in this region.”

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “台韩陆雄踞晶片制造 东南亚蓄势力争上游”.