Built for chaos: Why China’s robotaxis are streets ahead

Chinese robotaxis — Apollo Go, Pony.ai and WeRide — lead globally by mastering chaotic traffic and keeping costs low, outpacing US rivals Waymo and Tesla as autonomous services expand worldwide. Hedge fund CEO Taylor Lynch Ogan and US academic Chen Xiangming survey the field.

In frontier technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), where China and the US race for advantage, autonomous driving — robotaxis in particular — has diverged in terms of adoption speed, scale and technical capability.

As with AI, the rollout and operation of robotaxis in China and the US are dominated by a small handful of firms, notably Apollo Go and Waymo. But unlike AI — where American companies still lead — China’s leading robotaxi operators, Apollo Go, WeRide and Pony.ai, appear to be pulling ahead of Waymo, even before Tesla has launched a robotaxi service or begun international expansion.

This article takes a comparative look at how China’s dominant robotaxi firms have fared against their US counterparts, examining differences in competitiveness and technological trajectories. Co-author Ogan commutes daily by robotaxi in Shenzhen and has owned Teslas equipped with Full Self-Driving, as well as ridden in Waymo and Pony.ai robotaxis in the US.

Tech race to 10,000-hour mark

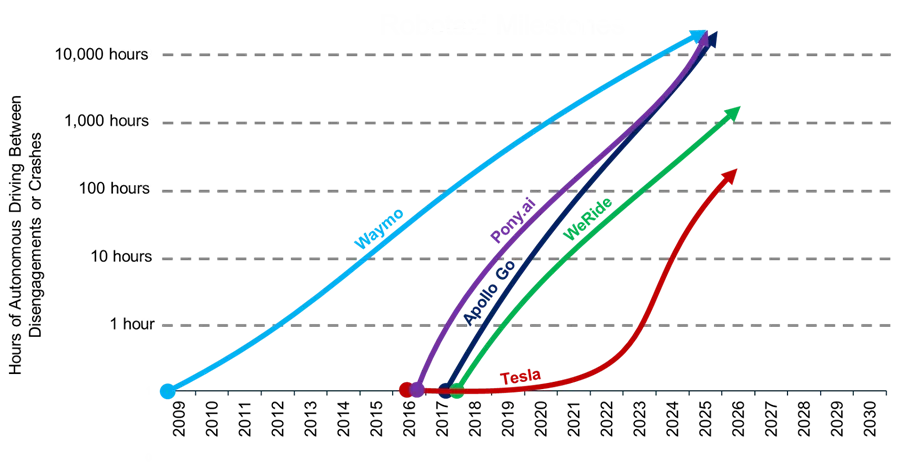

In autonomous driving, progress is measured in levels, metrics and milestones. The most widely watched metric is how long a system can drive without a crash or human intervention. Roughly 1,000 hours of uninterrupted driving is often cited as approaching human-level performance, while around 10,000 hours of fully autonomous, crash-free operation is commonly viewed as a benchmark for a commercially scalable robotaxi service.

Waymo reached one hour of autonomous driving in 2012, three years after the programme started. Pony.ai achieved one hour in 2017, just one year after it was founded by two Chinese Computer Science PhDs, both of whom had previously worked at Google and Baidu.

Only three companies are scaling robotaxis in meaningful numbers: Waymo, Pony.ai and Apollo Go.

Only three companies are scaling robotaxis in meaningful numbers: Waymo, Pony.ai and Apollo Go. All three appeared to surpass the 10,000-hour mark in 2025, which is when they started scaling commercial service to new cities. Pony.ai’s co-founder and one of the world’s best coders, Dr Tiancheng Lou, said in an August 2024 interview that many companies get stuck at the 100-hour to 1,000-hour stage, including Tesla.

Dr Lou said, “After reaching 1,000 hours, you need to start considering the drawbacks of data. Human driving behaviour varies under different circumstances, which can confuse machine learning models. The system doesn’t know who to learn from, and it can’t just take an average because there’s no true average in driving behaviour.”

China’s LiDAR leap

When Google launched its self-driving car project in 2009, it relied on Velodyne’s HDL-64E LiDAR sensor, which cost upwards of US$75,000 per unit. At Tesla’s 2019 Autonomy Day, CEO Elon Musk famously dismissed LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) as a “fool’s errand”, declaring that “anyone relying on LiDAR is doomed” due to its expense and aesthetic. Musk insisted on building a team convinced that a camera-only approach was the most practical path for scalable robotaxis, betting on monumental advances in computer vision and machine learning in the years ahead.

While advancements in such fields have been achieved, Musk did not anticipate the emergence of China’s LiDAR manufacturing ecosystem. Beginning around 2016, Chinese companies, including Hesai Technology, RoboSense and Huawei, entered the market with aggressive cost reduction strategies, applying vertical integration, automated production and economies of scale.

The results have been dramatic: by 2024, Chinese companies controlled 88% of the global automotive LiDAR market, with RoboSense’s MX series selling for under US$200 per unit and Huawei promising prices below US$100 within two years. Today, most new electric vehicles (EVs) in China priced over US$30,000 have at least one LiDAR sensor, and recent regulatory filings in China revealed BYD’s US$10,000 Seagull will soon come with a forward-facing LiDAR sensor for driver assistance.

Waymo developed its LiDAR in-house beginning in 2011, claiming by 2017 to have reduced per-unit costs to approximately US$7,500 — still at least 15 times higher than Chinese-manufactured alternatives. Waymo’s sixth-generation vehicles use four LiDAR sensors alongside 13 cameras and six radar sensors, with total sensor array costs estimated between US$40,000 to US$50,000 per vehicle. For Chinese robotaxi operators paying a few hundred dollars per LiDAR unit, this hardware cost differential represents a structural advantage that compounds with every vehicle added to their fleets. For example, an Apollo Go robotaxi costs as low as US$28,000, a fraction of Waymo’s six-figure per-vehicle expense.

Despite starting later, all three Chinese robotaxi companies have caught up with Waymo in fleet size, rides completed, and the number of cities in service.

Leaders and challengers

With a head start in 2009 as Google’s self-driving car project, Waymo has travelled the longest in blazing the trail of autonomous driving and reached arguably pole position in driverless ride-hailing service today since launching commercial service in Phoenix in 2018.

As of 17 November 2025, Waymo ran over 250,000 trips per week across San Francisco, Los Angeles, Austin, Atlanta and Phoenix. It had recorded more than ten million paid rides and over 100 million autonomous miles on public roads. Waymo reached this scale of service rapidly. With a growth rate of 12.9% over the most recent period (27 February 2025-24 April 2025), with released data, Waymo was estimated to average almost 360,000 trips per week through August 2025. Despite starting later, all three Chinese robotaxi companies have caught up with Waymo in fleet size, rides completed, and the number of cities in service, as seen in this comparison table.

Tesla’s robotaxi project, started in 2016, is still not commercialised a decade later. Ironically, its EV and self-driving lead has not yielded a robotaxi edge. Chinese firms, by contrast, leverage a crowded EV market to reduce costs and gain a structural advantage.

Tesla started a limited, supervised pilot in Austin, Texas, around June 2025, using Model Y vehicles with their “Full Self-Driving” software, a safety monitor for invited users, and service confined to a geofenced area, later expanded to 90 square miles. Despite securing a permit to operate in Arizona and showing off its Cybercab in Shanghai, where it operates a gigafactory making its popular EV models with a 95%-localised supply chain, Tesla continues to fight an uphill battle on safety for its self-driving technology, given its earlier crash accidents.

To really compete with Waymo and its Chinese rivals, Tesla will need to expand geographically, but the ultimate winner will be one that can operate safely, earn passenger trust, and navigate complex regulations.

Tesla’s robotaxi service initially operated with a dedicated app, camera-based Full Self-Driving software, and required user agreements and in-car supervision, although a more advanced version of Full Self-Driving was offered later, and no human was required behind the wheel by December 2025.

With these improvements, Tesla is trying not to fall too much behind Waymo while it continues dealing with occasional technical and safety issues, such as hard braking and navigating wrong ways; although Waymo also had to respond to recent safety concerns of its robotaxi illegally passing stopped school buses with red lights flashing.

Nevertheless, one software engineer critic remarked, “[Elon Musk] is trying to make people think that they’re in the same league as Waymo. They’re not.” To really compete with Waymo and its Chinese rivals, Tesla will need to expand geographically, but the ultimate winner will be one that can operate safely, earn passenger trust, and navigate complex regulations.

Keys to China racing ahead: all-nation support

Having followed Waymo’s tech formula in combining LiDAR, radar, cameras and precision GPS, the Chinese robotaxi firms have done better largely due to China’s tremendous cost advantage from its manufacturing strength.

While cost favours Chinese robotaxi companies, government support is more critical. Waymo and Tesla’s robotaxi operations are more market-driven, whereas their Chinese competitors are government-driven, as autonomous-driving technology is considered a strategic sector by China, which aims to become the world leader in driverless vehicles by 2035. This government support also includes subsidies and more generous approval of permits, as evidenced by over 50 cities across China having introduced testing-friendly policies for autonomous vehicles. If the Chinese robotaxi companies can continue to ride on these competitive advantages, they can take a larger share of the global market for driverless taxi service, which is projected by Goldman Sachs to be worth US$25 billion by 2030.

Chinese firms, having forged their autonomous driving stacks on some of the world’s most demanding urban streets while benefiting from domestic LiDAR cost advantages, a cheaper commute, more willing customers and local governments willing to experiment in new mobility methods, appear better positioned than their US counterparts for this next phase of competition.

... whether its [Waymo’s] system could handle the chaotic environments Chinese competitors navigate daily remains an open question many industry observers doubt would be answered favourably.

The ultimate test: road complexity and global scalability

Chinese cities present driving conditions categorically different from Waymo’s operating areas. In Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan and others, robotaxis must contend with dense urban traffic, electric scooters weaving unpredictably through lanes, aggressive merging, frequent jaywalking and drivers who treat traffic rules as guidelines rather than absolutes. Co-author Ogan, who commutes daily via robotaxi in Shenzhen, can attest that navigating a Chinese urban centre requires constant negotiation with electric bikes, pedestrians crossing mid-block, and drivers who routinely ignore lane markings.

While the main Chinese robotaxi companies have an excellent safety record, there was an accident on 6 December 2025, when a taxi of Hello Robotaxi, a lesser-known Chinese company, ran over and injured a pedestrian who fell on a slippery street in the Chinese city of Zhuzhou, Hunan province. Alarming as it was, the accident was predated by Hello Robotaxi’s agreement with both the Ant Group affiliated with Alibaba and Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. (CATL) to conduce R&D on L4 or high driving automation technology, which will improve safety further. With around 80 taxis already running on 297 designated kilometres in Zhuzhou, Hello Robotaxi plans to deploy 50,000 new and safer vehicles in multiple Chinese cities in 2027. This points to the fierce competition among the established and up-and-coming Chinese companies in market expansion as they continue to ratchet up safety standards.

American cities where Waymo operates — Phoenix, San Francisco, Austin — feature more predictable traffic patterns, far less density, wider lanes, and drivers who generally adhere to traffic laws. Crucially, the top Chinese robotaxi firms have demonstrated they can operate on American roads: Apollo, Pony.ai, and WeRide have held California DMV permits and logged hundreds of thousands of test miles over the last decade.

The reverse has never been attempted — Waymo has announced expansion plans for London and Tokyo but has never indicated any intention to operate in China, and whether its system could handle the chaotic environments Chinese competitors navigate daily remains an open question many industry observers doubt would be answered favourably.

As the global robotaxi market expands, the question of which companies can adapt their technology to diverse, challenging road environments becomes paramount.

As robotaxi services expand globally to Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Latin America and Africa, they will encounter driving environments resembling Chinese cities far more than American suburbs — roads in Jakarta, Mumbai, Nairobi and São Paulo feature the same mix of aggressive drivers, informal traffic rules, and diverse vehicle types that Chinese robotaxis already navigate successfully.

It is also notable that Tesla’s challenges in China extend beyond technology: in early 2025, Chinese regulators required Tesla to rename “Full Self-Driving” to “Intelligent Assisted Driving” amid restrictions banning terms like “self-driving” in advertising to prevent misleading consumers, and Tesla’s subsequent FSD trial was ended shortly after. These regulations requiring accurate terminology and technical disclosure did not impact China’s established robotaxi operators, whose systems already operate at higher autonomy levels.

As the global robotaxi market expands, the question of which companies can adapt their technology to diverse, challenging road environments becomes paramount. The ultimate winner may not be determined by who can navigate San Francisco’s grid, but by who can handle the world’s most complex roads. And China is already meeting that test.