Chinese tech giants’ struggle to power AI data centre boom

The rise of intelligent computing centres, dubbed “AI brain factories”, has sent data centres’ energy consumption soaring. How are operators securing reliable, cheaper electricity while also trying to meet the government’s green power targets?

(By Caixin journalists Zhao Xuan, Qin Min, Fan Ruohong and Wang Xintong)

China’s rapidly expanding demand for artificial intelligence (AI) computing has sent data centres’ energy consumption soaring. Securing reliable, cheaper electricity is crucial but proving challenging for operators trying to meet the government’s green power targets.

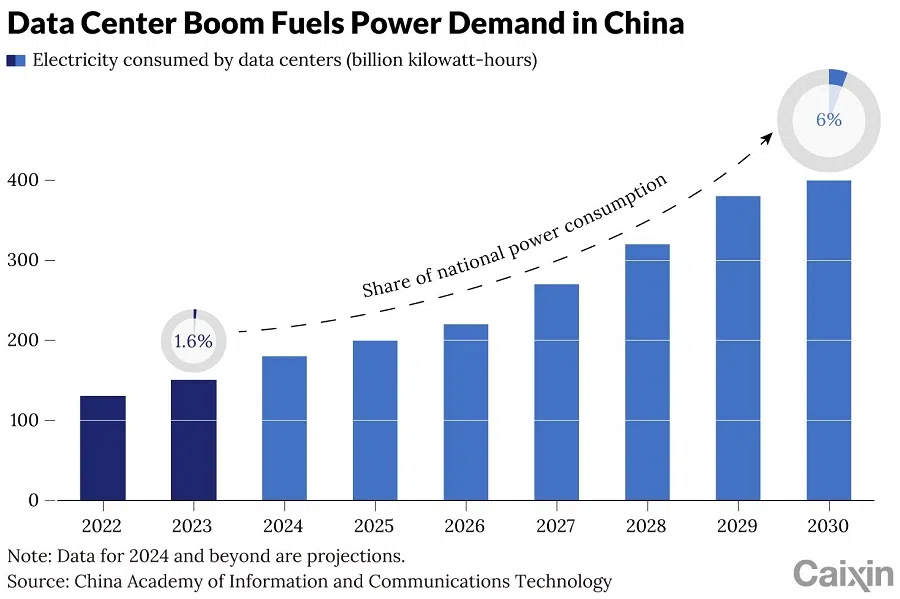

In 2024, China’s data centres consumed approximately 140 billion kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity, a 31% year-on-year surge that far outpaced the 6.8% growth in the country’s total power consumption...

The wind- and solar-rich regions in the west of the country could be a solution, if industry players are willing to relocate from the more developed coastal areas in the east.

In 2024, China’s data centres consumed approximately 140 billion kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity, a 31% year-on-year surge that far outpaced the 6.8% growth in the country’s total power consumption, Han Bing, a senior research analyst at S&P Global Commodity Insights, told Caixin. This figure could reach 400 billion kWh by 2030, raising data centres’ share of national power consumption from under 2% to 6%, according to the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT).

The spike is driven by the rise of intelligent computing centres, dubbed “AI brain factories”, which process vast datasets to train and operate large language models (LLMs). These facilities typically consume from 20 to 130 kilowatts per server cabinet, compared to just 5 to 10 kilowatts for traditional cloud data centres, Li Jinbo of IEIT Systems Co. Ltd. told Caixin. Large data centres can hold anywhere from thousands to tens of thousands of server cabinets.

With China’s intelligent computing scale expected to grow at 33.9% annually from 2022 to 2027, according to IT services provider IDC, the strain on energy infrastructure is intensifying.

To balance surging energy demand with its 2030 carbon peak and 2060 neutrality targets, China is steering data centres toward western regions, where abundant wind and solar resources remain underutilised.

But for companies venturing west, the path is not well-trodden. These areas lack the infrastructure, talent, and customer base of eastern hubs, while renewable power sources are infamously unstable and will not necessarily be cheaper than the national supply.

Policy vs reality

In July last year, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and two other government agencies jointly released a low-carbon development plan for data centres. Among the targets is increasing the utilisation rate of renewable energy at data centres by an average of 10% annually through the end of 2025.

To achieve this growth, data centres will need to source approximately 40 billion kWh to 63 billion kWh of electricity from solar and wind power by the end of 2025, said Qin Weixiao, a senior research analyst at S&P Global Commodity Insights.

But while western regions boast abundant wind and solar resources and lower electricity prices, they often lag in infrastructure development.

The challenge lies in efficiently marrying abundant green energy resources in the less developed western regions with the growing data processing needs east.

“Computing demand is concentrated in the eastern regions, where the electricity self-sufficiency rate (in renewables) is less than 40%, while the west has 70% of China’s renewable energy installed capacity,” said CAICT engineer Huang Wei.

To bridge this structural imbalance, the government launched a project in 2022 to channel more computing resources from the east to the west. This strategy includes creating national computing hubs, such as the northwestern Ningxia Hui autonomous region, which has consequently drawn investment from many companies, including China’s three major telecom providers — China Mobile Ltd., China Telecom Corp. Ltd. and China United Network Communications Group Co. Ltd. (China Unicom) — as well as tech giants like Baidu Inc. and Tencent Holdings Ltd.

Tencent has plans to build its largest intelligent computing centre in western China in Ningxia, partly due to the region’s low electricity prices, Caixin has learned.

Companies are more inclined to train their LLMs in western provinces because electricity prices are lower, but base their application-oriented data centres in the east where a larger customer base enables faster feedback on their apps, according to an industry source.

“Electricity accounts for the lion’s share of data centre operating costs — we obviously want it to be both green and affordable,” one industry source told Caixin. But while western regions boast abundant wind and solar resources and lower electricity prices, they often lag in infrastructure development. Specifically, shortfalls in transportation, communication and talent support systems make it difficult to attract and retain high-tech personnel, multiple sources said.

... wind and solar are unstable power generators, and power grids may struggle to keep up with AI computing’s energy demands, potentially leading to power disruptions that could result in data loss and significant economic losses...

“Even with facilities, the lack of local teams to ensure stable operations will prevent computing resources from being efficiently utilised,” said Wang Shen, a principal analyst at technology research and advisory group Omdia.

Additionally, wind and solar are unstable power generators, and power grids may struggle to keep up with AI computing’s energy demands, potentially leading to power disruptions that could result in data loss and significant economic losses, according to CAICT’s Huang and Peng Chengyao, director for Greater China power & renewables research and analysis at S&P Global Commodity Insights.

“Even a few seconds of interruption are unacceptable to customers,” Peng said.

Green power’s hard limits

In November, Tencent launched a “microgrid” in Huailai, Hebei province. The project utilises wind and solar energy and is equipped with a battery storage system to power a locally built data centre. The company said it is the first project of its kind in China.

A source close to Tencent told Caixin that the project can help the company save over 3.5 million RMB annually (US$486,000) — about one-sixth of the total electricity cost.

However, the clean power generated falls far short of demand, limiting both its environmental benefits and cost savings.

The project can generate 14 million kWh of electricity annually, just 15% of the data centre’s total electricity demand of 100 million kWh per year. “Based on our calculations, having a 40% direct green power supply ratio is optimal for a large data centre, ensuring stable power while minimising costs,” the source close to Tencent said.

Tencent has pledged to power its data centre operations with 100% renewable electricity by 2030. To meet this goal, it must source the remaining 85% of the data centre’s electricity from the state grid. Purchasing electricity from the state grid costs more than running on self-generated renewables.

Tencent’s case is just one example of how companies’ efforts to save costs and reduce emissions in data centres are hampered by infrastructure constraints and government policies.

Moreover, Tencent’s Huailai data centre is not operating at full capacity; if fully utilised, its annual electricity consumption could quadruple to 400 million kWh.

Tencent’s case is just one example of how companies’ efforts to save costs and reduce emissions in data centres are hampered by infrastructure constraints and government policies.

For many data centres, on-site clean power relies on rooftop solar panels, known as distributed photovoltaic (PV) power. But “due to equipment like cooling towers on rooftops, the area available for solar panels is limited and mostly used for lighting”, a person familiar with the operations of data centres said.

The result is the power generated from rooftop solar panels can meet less than 5% of data centres’ total electricity demand, Qin said. In contrast, rooftop solar can often meet 20-30% of electricity demand in manufacturing plants.

In addition, the National Energy Administration mandates that for self-consumed solar power systems, both the energy user and the distributed PV panels should be within the same property limits, according to guidelines issued in January. In Tencent’s case, the company can only build renewable projects at the industrial park where the data centre is located, which also limits its power generation capacity.

The source close to Tencent expected future policies to ease site restrictions, permitting large renewable energy projects to be built beyond industrial park boundaries to directly power data centres inside.

Local governments’ balancing act

In recent years, some northern and western areas have offered heavily subsidised electricity prices for data centres. Qingyang in Gansu province and Zhongwei in Ningxia offer rates as low as 0.36 RMB per kWh, while Guiyang, Guizhou province, and Ulanqab in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region provide about 0.35 RMB per kWh.

Local governments in these regions are aiming to boost their local digital economies by attracting companies with massive demands for computing power.

In comparison, typical industrial and commercial electricity prices are over 0.6 RMB per kWh.

Local governments in these regions are aiming to boost their local digital economies by attracting companies with massive demands for computing power.

“This round of large-scale data centre construction is more driven by the demand for new infrastructure promoted by local digital economy development,” an industry analyst said.

Qingyang, for example, has made its local computing industry a key focus for its economic development. Every RMB invested in computing can generate 3 to 4 RMB in local economic output, said Bian Tao, director of the local supervisor overseeing state-owned firms, according to a state media report last year. Bian added that Qingyang’s digital economy output is expected to surpass 100 billion RMB this year, with a target of 270 billion RMB by 2030.

Ulanqab is also capitalising on the growing demand for computing centres to boost its digital economy. As of early May, 36 data centres were built in the city, including 33 intelligent computing centres, with total investments exceeding 140 billion RMB.

However, companies drawn to western regions by cheaper electricity actually face uncertainty about how long the subsidies will last, as local governments walk a tightrope in driving local economic development while enforcing Beijing’s ambitious carbon reduction goals.

In September 2022, Inner Mongolia ended years of preferential electricity pricing for certain companies. The move complied with an NDRC directive to abolish “unreasonable electricity subsidies”, while also addressing concerns over energy waste, emissions and environmental violations flagged by other national authorities, the regional development and reform commission said in a statement.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “In Depth: Chinese Tech Giants’ Struggle to Power AI Data Center Boom”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)