Vietnam's rare earth ambitions: Economic and strategic drivers

Vietnam is seeking to develop its rare earth industry at a time when global demand for such minerals is increasing. Its motivations are not merely economic, but also strategic.

According to the US Geological Survey, Vietnam has the world's second-largest reserves of rare earths after China, with an estimated 22 million tonnes accounting for around 19% of the world's known reserves. However, despite numerous attempts to develop the rare earth industry, including collaborations with Japanese investors in the early 2010s, little progress has been made and Vietnam has yet to successfully launch its rare earth industry.

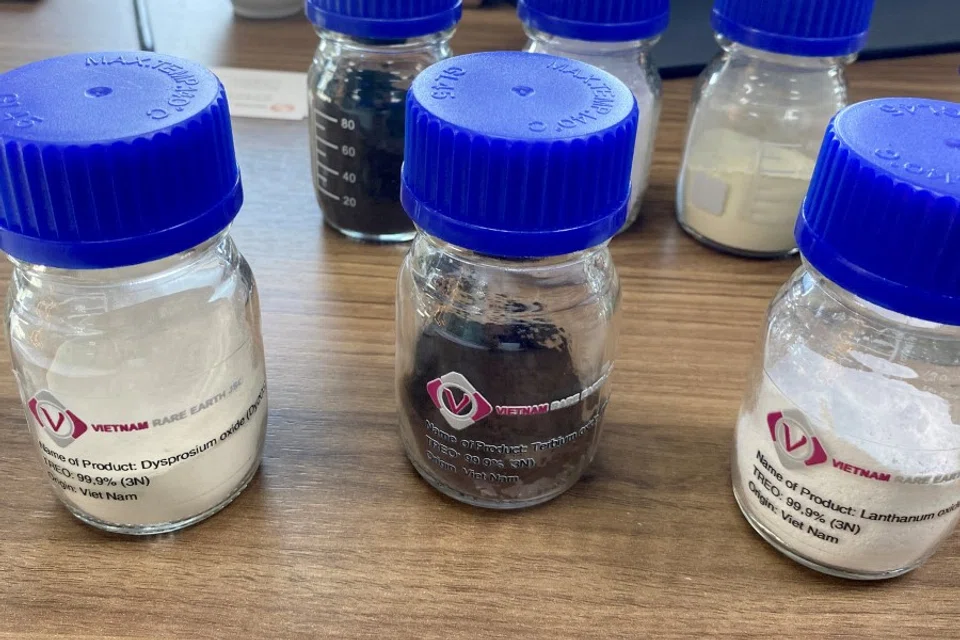

But things appear to be changing quickly. In July, the Vietnamese government released a master plan for the mineral sector which aims to exploit and process more than 2 million tonnes of rare earth ores by 2030, and produce up to 60,000 tonnes of rare earth oxides equivalent per year. On 18 October, the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology and the Ministry of Science and Technology held a conference to discuss the development of the rare earth industry. Vietnam also plans to auction mining rights for several areas of Dong Pao, the largest rare earth mine in the country, before the end of the year.

Difficulties in developing Vietnam's rare earth industry

Unlike other extractive industries such as oil and gas or coal, the rare earth industry, despite its strategic importance, remains relatively small. According to Research Nester, the global rare earth metals market in 2022 was worth around US$10 billion, and is projected to grow at a compound annual rate of 8% to reach a total revenue of US$20 billion by 2035. If Vietnam is successful in developing its rare earth industry to make up 10% of the global market by then, it could potentially generate an annual revenue of approximately US$2 billion.

However, the potential profits could be significantly lower if all production costs are taken into account. These comparatively modest economic gains, combined with the lack of appropriate technologies and environmental concerns, may have delayed Vietnam's previous efforts to develop the industry.

Washington and its allies have sought to diversify rare earth supplies away from China. Besides reviving its own rare earth mines, it has also increased cooperation with Vietnam to develop alternative supplies.

Vietnam's recent efforts to develop the industry can therefore be better explained by the strategic benefits it hopes to gain, particularly its growing strategic importance to the major powers in the context of the intensifying US-China rivalry.

An alternative to China

China currently accounts for 63% of the world's rare earth mining, 85% of rare earth processing, and 92% of rare earth magnet production. Rare earth oxides as well as rare earth alloys and magnets that China controls are critical components in important industries such as electronics, electric vehicles, and wind turbines. They are also essential to the production of advanced armaments, including missiles, radars, and stealth aircraft.

This has led to a risky dependence on the part of the US and its allies on China's rare earth exports. Washington, for example, currently sources about 74% of its rare earth imports from China. In 2010, China allegedly imposed a ban on rare earth exports to Japan due to a maritime dispute, raising the possibility of a similar ban on exports to the US. Since August, China has restricted the export of germanium and gallium, which are critical components of certain high-tech products, further raising the alarm in Washington.

Washington and its allies have sought to diversify rare earth supplies away from China. Besides reviving its own rare earth mines, it has also increased cooperation with Vietnam to develop alternative supplies. During President Joe Biden's visit to Hanoi in September, the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to aid Vietnam in quantifying its rare earth resources and economic potential, as well as attract quality investment for the sector.

Last month, Emily Blanchard, chief economist of the US State Department, stated during her visit to Hanoi that the US views Vietnam as a key partner in ensuring mineral security, and is ready to support Vietnam in preparing auctions for its rare earths mines, as well as provide technical assistance to help develop the industry.

In the long run, the industry can also bring the country other potential economic benefits, including integration into the global supply chains for high-tech products...

Some US allies have also expressed interest in collaborating with Vietnam to unlock its rare earth potential. During South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol's visit to Hanoi in June, the two countries signed an MOU to establish a joint supply chain centre for rare earths and minerals such as tungsten, in order to ensure a reliable supply chain for Korean companies. Several Australian investors, including Blackstone, have also voiced their intent to bid for mining rights at the Dong Pao mine.

Aiding Vietnam's economic development

If Vietnam can successfully develop its rare earth industry and become a reliable supplier of rare earth products for the US and its allies, this will significantly enhance Hanoi's standing in Washington and its allies' strategic considerations. This will help bolster Hanoi's relations with these partners, compensating for its reluctance to engage in certain sensitive defence cooperation activities with them.

In the long run, the industry can also bring the country other potential economic benefits, including integration into the global supply chains for high-tech products, which is essential for Vietnam's ambition to become an industrialised and high-income economy by 2045.

However, whether Vietnam is able to launch the industry as planned is yet to be seen. The most serious challenge for Vietnam now is to attract capable investors and acquire efficient and environment-friendly technologies for its ore processing facilities. The outcome of the auction of mining concession at Dong Pao mine in the coming months may provide further insight into these matters.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute's blogsite.